Illyanna Maisonet’s bona fides speak for themselves.

Her award-winning column about traditional Puerto Rican foodways in the San Francisco Chronicle made Maisonet the first Puerto Rican food columnist in the United States. She is as fierce an advocate for the city of Sacramento as you will ever find—particularly when it comes to the immigrant and working-class food businesses that populate her neighborhood in South Sacramento.

And when the glossy food magazine Bon Appetit had its racial reckoning moment of 2020, those who know Maisonet were not surprised that she was the one who kicked the whole thing off. Her series of tweets about the rationale the magazine offered for rejecting one of her pitches—and about the publication’s glaring lack of Puerto Rican food stories overall—ignited such a high-profile discussion of tokenism and racism in food media that the company eventually underwent a massive reshuffling of its leadership and staff. She’s never been shy about speaking truth to power.

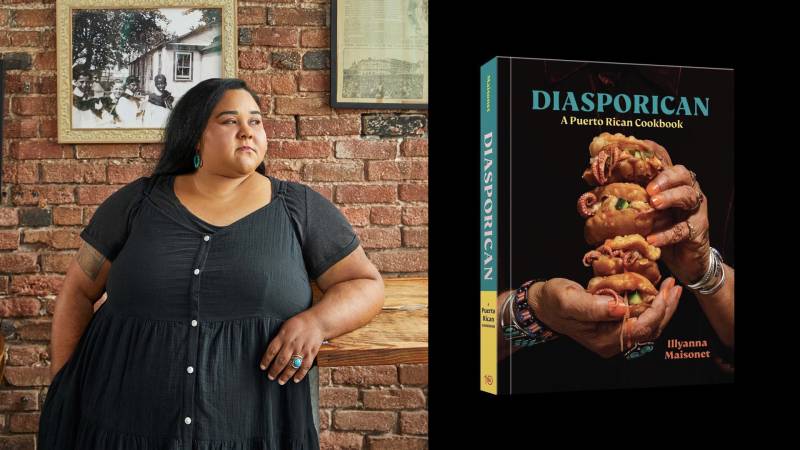

She also happens to be a beautiful writer. Maisonet’s full powers are on display in her forthcoming debut cookbook, Diasporican: A Puerto Rican Cookbook. “Culantro,” she writes, describing an herb central to Puerto Rican cooking, “is like cilantro’s cousin who comes to visit from the hood. Yeah, they’re family. But it’s also way more ‘punchy,’ ‘vocal,’ ‘spirited’—all those politically correct euphemisms—and possibly wearing FUBU.” About the salted codfish fritters known as bacalaitos, Maisonet writes, “The center was toothsome like our gente’s—our people’s—resistance, salty from the tears we’ve shed, but the edges were delicate and vulnerable, like when we reveal our underbellies.”

As its title indicates, Diasporican isn’t meant to be some all-purpose handbook on Puerto Rican cooking. Instead, it’s specifically a book that documents Maisonet’s experience as a Puerto Rican living in the diaspora here in Northern California—and the way the mix of cultures here has informed her cooking. It’s a book that deals with grief and childhood trauma and the long-reaching effects of American colonialism. It’ll also make you want to drop everything and immediately cook up a pot of arroz con gandules or carne guisada, or a sizzling hot plate of tostones.