It’s evident from the very start that the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s Joan Brown retrospective is going to be a bit different. It could have something to do with the painted walls that greet you off the seventh-floor elevator (peach and bright orange). It could be the deliciously unhinged wall text next to Joan + Donald, a 1982 painting of Brown holding a squirming tabby cat. (Hint: it involves declaring the cat a tax write-off and an IRS audit, no spoilers here.) But really it’s just the fact that this is a Joan Brown show, and Joan Brown was a singular artist.

Curated by SFMOMA’s Janet Bishop and Nancy Lim, this retrospective is the late San Francisco artist’s first in over 20 years. Following Brown’s career from her art school days at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute) to her untimely death at the age of 52, the show moves fluidly through Brown’s evolving style and subject matter. The extended pieces of wall text are full of delightful autobiographical details and images of Brown’s own paint-covered visual references.

It’s hard to believe, looking at her assured, large-scale figurative paintings, that Brown almost didn’t become an artist. She applied to CSFA — with a portfolio of drawings of movie stars — on the eve of her enrollment at an all-girls Catholic college. And she did not transition to art school easily. On the verge of dropping out after one year (her prim mother, aghast at the nude models, would have rejoiced), she took a summer painting course with Elmer Bischoff, who became a lifelong mentor and friend.

Bischoff encouraged Brown to paint the stuff of everyday life, teaching her to trust her own instincts above art world fads and critical responses (a lesson that would serve her well in the next three decades). In that class, Brown learned to love paint. Her pieces from those early years are thickly impastoed; some look like they could still be wet. Comically large brushes were involved — sometimes even trowels — as Brown layered large swaths of house paint in swirling images of women swimming; her son under a heavily decorated Christmas tree; dogs; her domestic space; and a Thanksgiving turkey.

Brown found remarkable and rapid success early in her career. Painted in 1959, that aforementioned turkey was purchased by the Museum of Modern Art in New York when Brown was only 22 years old. By 1964, her work had appeared on the cover of Artforum (the accompanying article dubbed her “Everybody’s Darling”), in group exhibitions at the Whitney, the San Francisco Museum of Art (now SFMOMA), and in two successful solo exhibitions with New York’s Staempfli Gallery. But she was disenchanted with her heavy brushwork, and, trusting her instincts, she decided to pursue a new direction in her work, refusing gallery shows for the next three years.

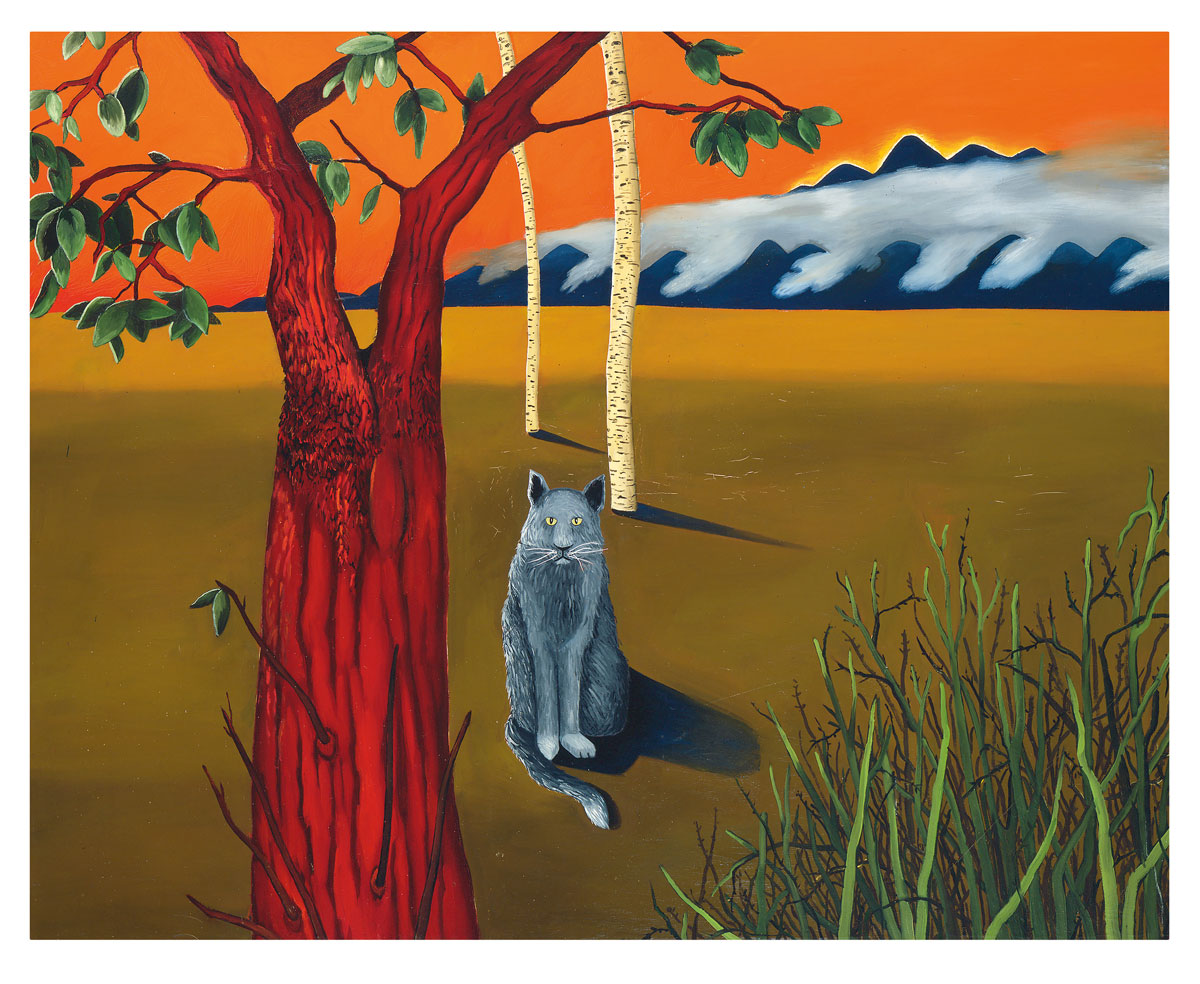

In the SFMOMA retrospective, this shift comes suddenly, via Gray Cat with Madrone and Birch Trees (1968), a large-scale canvas that references Henri Rousseau’s tropical landscapes. In comparison to her earlier work, this painting’s surface is nearly flat, its subjects rendered distinctly; a large gray cat stares out from a spare landscape of olive and ochre, topped by a nuclear orange sky. This is a deeply weird painting, a portal to another way of rendering Brown’s view of the world.