In Robert Zemeckis’ 1992 black comedy Death Becomes Her, Meryl Streep plays Madeline Ashton, an aging Hollywood actress who pays a pretty penny for an elixir from a mysterious rejuvenation expert (Isabella Rossellini’s Lisle Von Rhuman). The elixir not only de-ages her, but also immortalizes her youth.

In the pivotal transformation scene, she drinks the glowing pink potion and her butt is instantly lifted to a perkier position. The liver spots on her hand disappear. The gap between her breasts closes. And the skin on her face tightens and is visibly more supple, as if the collagen she naturally lost as she aged was returned to her. In sheer elation she exclaims, “I’m a girl!”

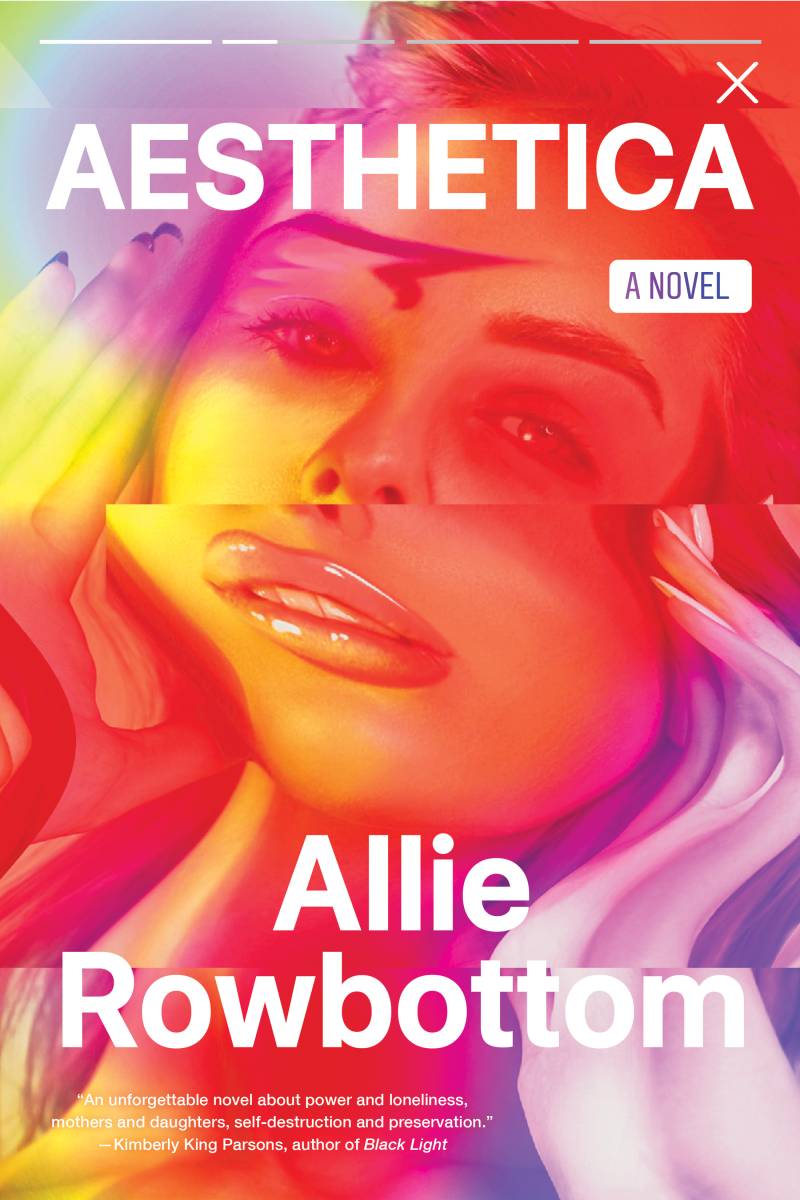

In 2022, these body transformations are possible through surgical lifts of the butt, breasts and face, or digitally through apps like Facetune, which has been downloaded upwards of 200 million times. In writer Allie Rowbottom’s debut novel, Aesthetica, there is an equally desirable and dangerous inverse surgery, one that restores bodies by undoing previous procedures. In her fictional world, the magic potion is an edit button with the power to delete.

Aesthetica’s protagonist, Anna Wrey, is a 35-year-old former Instagram influencer who has elected to have the Aesthetica surgery — a costly and experimental procedure that is only available in Los Angeles. That’s in the present day, in 2032. Back in 2017, she is a hungry but naive 19-year-old who gets wrapped up in Los Angeles’s influencer cult(ure) and is catapulted into mid-tier celebrity status with the help of a much older manager-boyfriend named Jake, who constantly uses and mispronounces the word “aesthetic.” The timing is a useful frame as Anna comes of age in a not-long-ago era, which The New Yorker’s Jia Tolentino declared “The Age of Instagram Face” in a 2019 essay. Readers can readily remember the clashing cultural mores, aesthetic goals and feminist beliefs that we continue to grapple with today.

Media outlets that cover beauty constantly announce new trends as pathways to the ideal body. The Brazilian butt lift came to define the 2010s despite worryingly high mortality rates. And more recently, as The New York Post noted crassly, some celebrities have returned to the “heroin-chic” thinness of ’90s supermodels. The constant stream of new beauty and body trends, some cyclical, some diametrically opposed, are a reminder that the concept of an ideal body was only ever meant to be a marketing goldmine, not an achievable goal. On TikTok, videos tagged ‘plastic surgery’ have reached over 15 billion views and birthed a cottage industry of plastic surgeons analyzing people’s faces.