Ricky Ybarra was looking for a fresh start. He’d been laid off and ended a long-term relationship, and needed a new place to live. In June, after a call with Betsy Ann Cowley, he thought his luck might turn around. Cowley offered the 40-year-old chef work on her property, a former ghost town in the Sierra Nevada called Pulga.

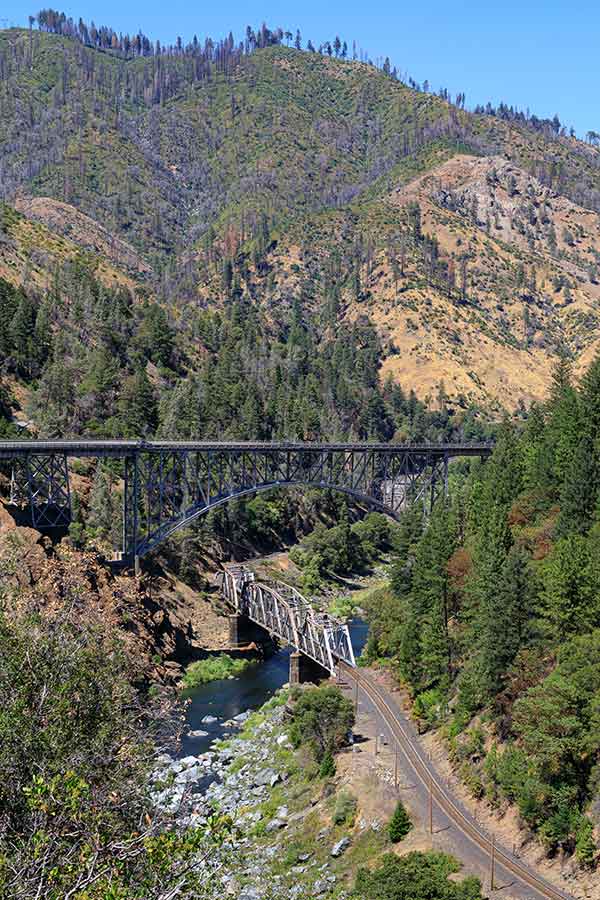

A mining settlement established in 1906 near Chico, Pulga is located at the edge of the Plumas National Forest in rural Butte County — the site of the deadly 2018 Camp Fire. With the help of her stepfather, Cowley, 35, acquired the 64-acre former town in 2015, and began running it as a rustic resort, renting 11 cabins on Airbnb and hosting weddings, corporate retreats and events.

Ybarra says Cowley verbally offered him — and, later, his girlfriend, sous-chef Sosha Young — cooking gigs for her summer events. As musicians, the two found Cowley’s vision of an intentional community attractive. Pulga had a reputation as a refuge for creatives: Cowley was once a resident of Oakland’s Fifth Avenue Marina artist enclave, and a glowing Bust Magazine profile portrayed her as an eccentric frontierswoman running a “feminist haven” orbited by writers and architects. Young and Ybarra were sold.

Shortly after their arrival, however, the two say they found something more sinister. As they tell it, Cowley began assigning additional work without pay, and invaded their privacy in ways that made them feel violated. After they left Pulga in August, Young and Ybarra both filed separate wage claims with the California Labor Commissioner’s Office.

“She essentially began treating us like her personal indentured servants, so we left without payment,” Young, 31, wrote in her complaint to the state, which she shared with KQED.

KQED spoke with six people who worked in Pulga between 2019 and 2022, most of whom are artists from the Bay Area. In interviews, several accused Cowley of wage theft, and said they’re still dealing with setbacks after their time in Pulga.

Taken together, their accounts demonstrate the lengths to which artists will go for opportunity and income, particularly during the pandemic. The workers claim that Cowley enticed them with flexible jobs, access to nature and space to create, but then withheld pay, leaving them broke, desperate and, in some cases, fearing for their safety.

In a series of interviews, emails and text message exchanges with KQED, Cowley denied nearly every allegation made by her former workers, and frequently changed the subject by accusing them of damaging property or violating rules.

Amid a string of sometimes erratic communications, Cowley emailed text message screenshots to KQED in which her friend appeared to threaten one of the sources in this story. (“I’m gonna make their lives hell … I just enjoy making people cry,” the text read.) She also claimed the Labor Commissioner’s Office told her “there is nothing there” regarding the wage disputes. But according to a department spokesperson, the cases are pending review.

“She just counts on people going, ‘I don’t want to lose this opportunity,’ that’s why they’ll do whatever for her,” says Ybarra. “But we just said, ‘We quit.’ She’s like, ‘No, that’s not how this game is played. I accuse you of some dumb shit, you grovel and you do the thing for me,’ and then it goes on and on. And we didn’t play that game with her.”

‘We were on eggshells’

In June, Cowley hired Ybarra and Young to cook for her summer events at a rate of $200 per day, the two say. According to their account, she also offered a cabin and access to utility vehicles, and a space to practice and record music in their spare time. The couple says they trusted Cowley because, at the time, she was married to Ybarra’s former boss at Oakland’s Starline Social Club, Adam Hatch. (Hatch, who recently stepped down as a managing owner of Starline, declined to be interviewed for this story.)