Growing up, I assumed fruit custard was a uniquely Indian food, no different than khichdi or palak paneer. Chilled fruit custard, sweetened with apples, bananas and grapes, made frequent appearances at my mother’s dinner parties, indistinguishable from other milky Indian desserts like kheer or shrikhand. I never saw anything similar to it in American restaurants or at my white friends’ houses: How could I guess it was anything other than Indian?

“Oh my god, I thought the same thing about fruit salad and Filipinos,” confesses blogger, baker and recipe developer extraordinaire Abi Balingit. We are chatting about her new memoir-cum-cookbook Mayumu: Filipino American Desserts Remixed, which documents the sweets she ate and made growing up in the Bay Area’s thriving Filipino communities.

“Our fruit salad has canned fruit, too, but we add more Filipino stuff like coconut jellies and sugar palm fruit, so I always thought it was 100 percent Filipino,” Balingit says. “Another product of colonialism and imperialism for sure.”

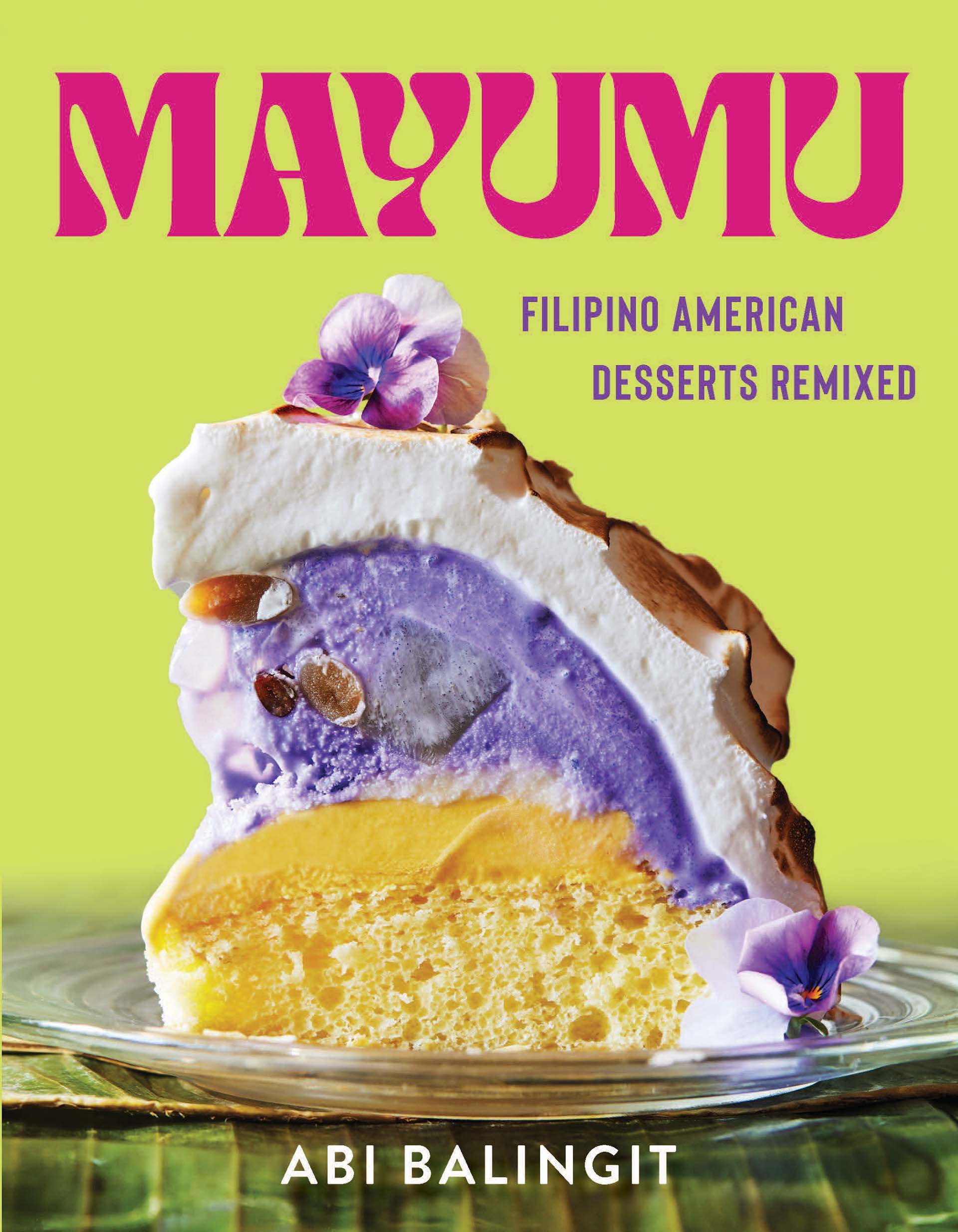

Our respective fruit salads and custards reflect a bizarre quirk of history, where the legacy of colonization and globalization has influenced our food to the point where the term “fusion” doesn’t really mean much. Asian cooking has been fused with Western culture. So why not make, say, a baked Alaska with ube ice cream — the tantalizing dessert displayed on the cover of Mayumu? Or a jello salad buko pandan?

“Obviously, growing up in America, the desserts are cupcakes, cakes and cookies — and these are things in the Philippines, too,” says Balingit. “I went to Seafood City or the small Filipino market and saw coco pie and ube pie, but at the same time I went to Safeway or Albertson’s and saw, like, Hostess and Little Debbie’s. There was nothing weird about it to me, there was no sense of foreignness or discomfort.”