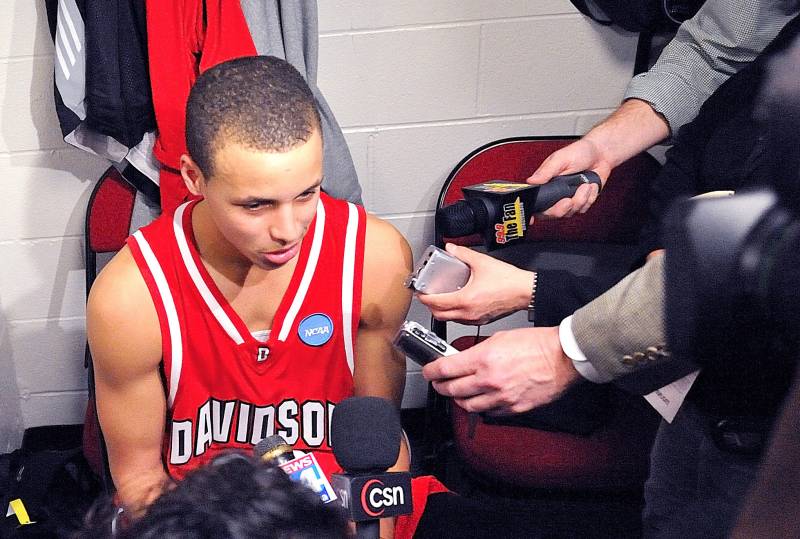

In a subtle way, I’ve been exploring that theme in Oakland. What’s at stake when people do not fully see you? Ryan [Coogler, this film’s producer,] told a story with extreme stakes with Oscar Grant — a young Black kid in a hoodie — about the consequences of not being seen as a whole person. Steph’s story is a version of that notion of how we only see the surface — a skinny kid, undersized, might get pushed around. With scouts and journalists, there’s a knee-jerk judgment there that gets layered on top of someone’s potential future. When that happens, it’s very difficult to overcome.

We found out how whenever family and a community see you and lift you up, and a mentor steps in and believes in you, powerful things happen. We’ve been unpacking that notion of being underrated and how it applies to athletes, communities, universities. It became a driving idea for Underrated.

In his lowest moments, Steph Curry had his family and Coach McKillop. Who was your mentor, and in what ways have you felt underrated?

In college, I had a significant drug problem and was arrested and sent to federal prison. When I got out, I was getting my life back together and went to Howard to study creative writing. That wasn’t even six years removed from me being in federal prison.

I got it in my head to study documentaries. UC Berkeley was a great place for that. Jon Else was a filmmaker there, and had been nominated for Oscars. He was a producer for the seminal PBS series about Civil Rights, Eyes on the Prize. I didn’t think I’d get in because of my grades and my record. [John Else] talked to me, he listened, he heard my story about why I was there and what I was hoping to achieve, what I had planned for the next five years. He advocated for my admission and I got in. That changed my life.

Because I was seen, despite what had happened to me and despite me not meeting the eye test, so to speak, I was nevertheless seen. I thought about that while making this movie: the parallels. I’m 6-foot-2. Steph is 6-foot-2. I’m mixed race. Steph is mixed race. I was born in Akron, Ohio. Steph was born in Akron, Ohio. How do you explain that? It goes back to the notion that all of us are connected and that we all need a sense of family and community to represent us.