To create the archive, Jahi sought out a partnership with a Black-led institution, and he found the right collaborator in AAMLO and its Chief Curator Bamidele Agbasegbe-Demerson. Prior to the Bay Area Hip-Hop Archives’ launch, AAMLO already had close to 12,000 artifacts and documents chronicling Black life in Northern California, from the Gold Rush to the Black Panther Party. “So we’re joining their community,” Jahi says. “And when we’re done, we’ll probably have about ten or 12,000 pieces from the Bay Area Hip-Hop Archives. It’s a level up — in terms of preservation, protection and, most importantly, the opportunity for artists to tell their story in their own voices so they are not erased.”

Beyond artists, the Bay Area Hip-Hop Archives honors people who’ve played a crucial role in facilitating the local scene, such as promoter Ankh Marketing, which has produced community events and big-name concerts with Goapele and Erykah Badu alike, and the Upper Room, a substance-free gathering space for the San Francisco spoken word and alternative hip-hop scenes of the ’90s. Other inductees include MC and queer party producer Aima the Dreamer; journalist, scholar and DJ Davey D (who serves as an advisor on KQED’s That’s My Word); dance historian and photographer Traci Bartlow; DJ Kevy Kev; the “Black Panther of hip-hop,” Paris; poet and educator Hodari Davis; and Phesto Dee of Souls of Mischief.

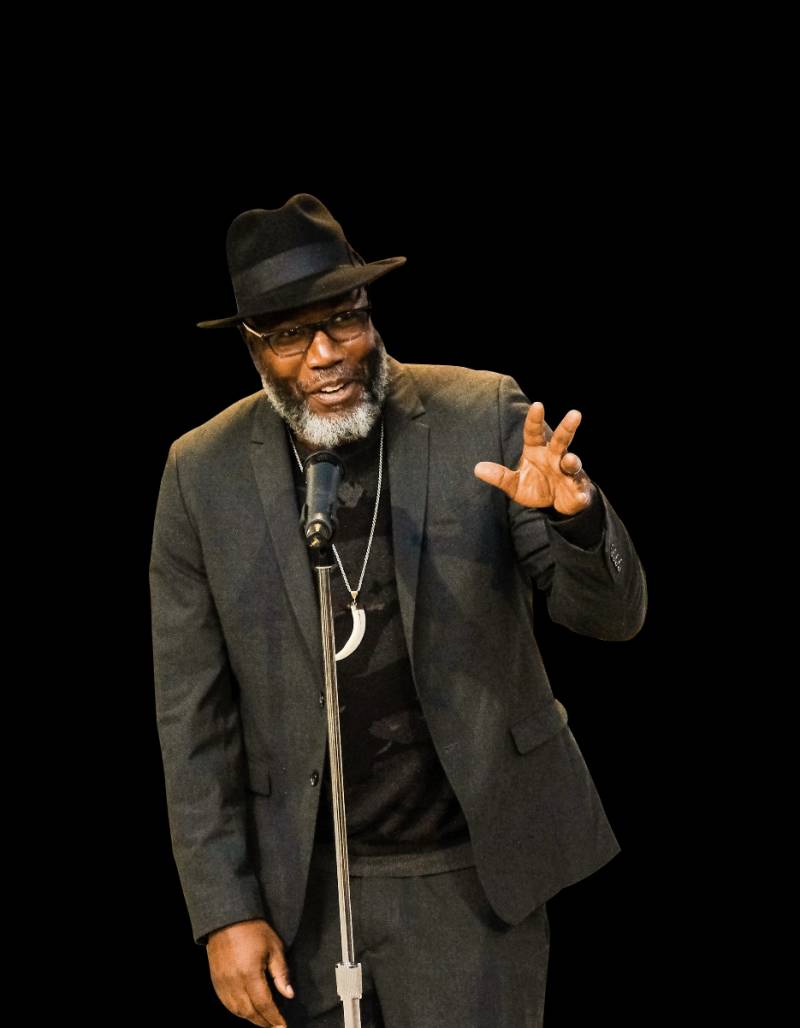

Jahi himself comes from the activist, alternative corner of hip-hop — what he refers to as the “socially conscious, mostly profanity-free, life-affirming lane.” He’s called Oakland home for 24 years, but he grew up DJing and freestyling in East Cleveland in the early ’80s. It was a turbulent time in American history, with the crack epidemic and rise of mass incarceration, and hip-hop offered him a sense of belonging and an artistic outlet. “All the rappers had perfect attendance, because we was always at school 30 minutes before school opened so we could battle,” says Jahi.

Jahi’s path into music was somewhat unconventional: He had a successful career at an educational nonprofit before embarking on a professional music career at 28 years old, in the late ’90s. Public Enemy’s Chuck D and KRS One gave him some of his first big opportunities, which led to a major-label album and a successful stint in Europe. He later founded the production company Microphone Mechanics, which has been his springboard into museum exhibitions, theater and, now, the archives.

Jahi has an inclusive vision of hip-hop, and isn’t about creating a dichotomy of street-versus-conscious, mainstream-versus-underground — nor is he into shaming or excluding practitioners of the art form who are different from him. Instead, he wants to celebrate the many styles and philosophies, the collective efforts, that have made the culture such a potent form of expression. “Hip-hop is a house with many rooms, and we’ve been in the sex, drugs, violence, pimp, hustler room,” he says. “It’s not the whole house.”

At the unveiling of the Bay Area Hip-Hop Archives in February, artists spoke of unity and pride. “We built this community,” said Mystic. “We built this when we had no models. We created magazines, we produced albums, we threw events. We created what the dream needed to be, and it was grounded in the radically loving and socially political foundation that is Oakland.”