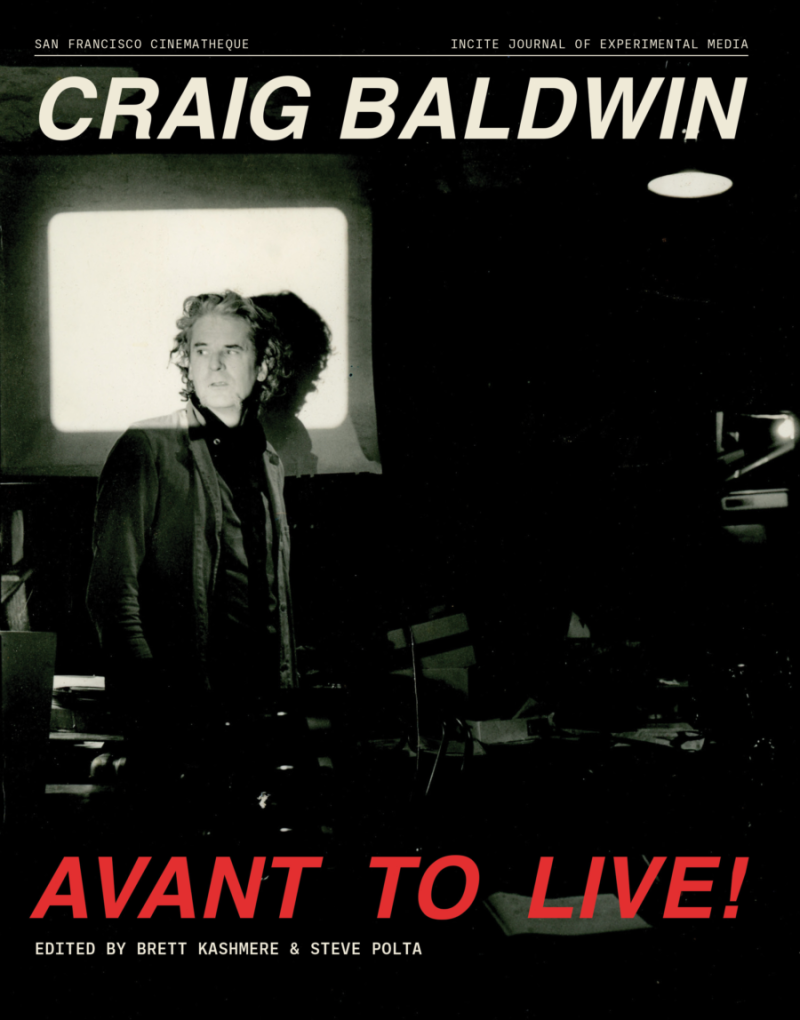

An enjoyable exception to the usual prestige books about artists, Craig Baldwin: Avant to Live! evokes the iconoclastic personality of San Francisco’s preeminent underground filmmaker and The Other Cinema curator.

Written and compiled by Bay Area artists and curators Brett Kashmere and Steve Polta (and just published by their respective organizations, INCITE Journal of Experimental Media and San Francisco Cinematheque), the massive tome frontloads a veritable trove of reminiscences, anecdotes, interviews and tributes before presenting an array of critical analyses.

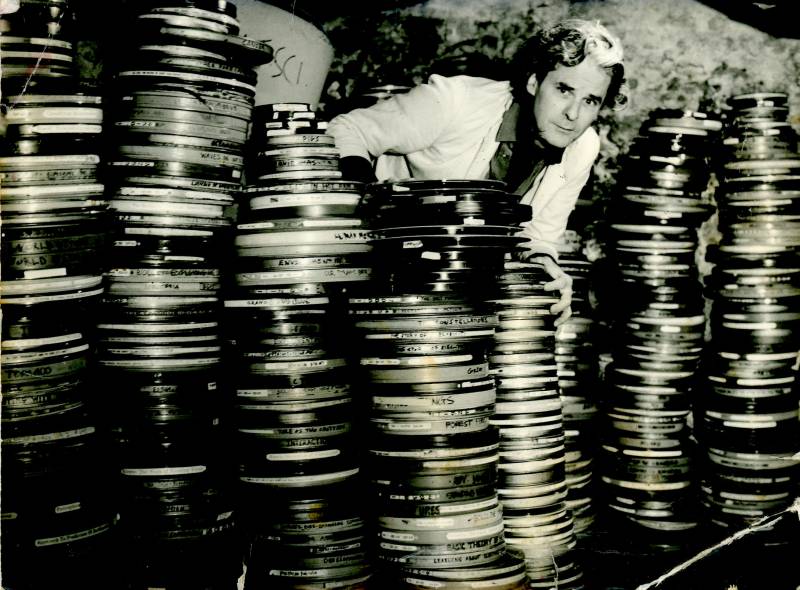

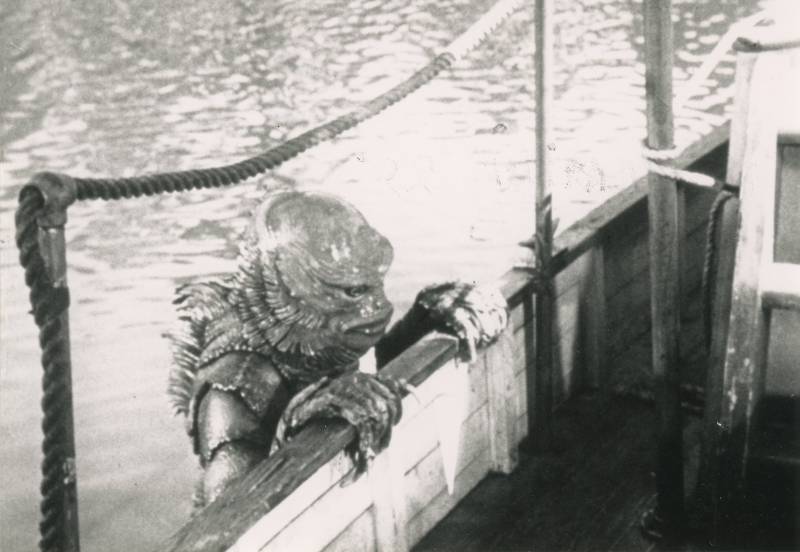

For more than 40 years, Craig Baldwin has reappropriated images from discarded and forgotten educational and industrial movies (found footage, in the vernacular of experimental film) to craft brilliant, hyper-dense 16mm films critiquing U.S. exceptionalism, colonialism, capitalism and moviemaking. Given that his works — Tribulation 99: Alien Anomalies Under America, ¡O No Coronado!, Sonic Outlaws, Spectres of the Spectrum, Mock Up on Mu — are subversive mashups of experimental documentary, science-fiction fantasia and essay film, it’s fitting that Craig Baldwin: Avant to Live is a hybrid zine, scrapbook, academic treatise and alternate social history of post-1970s San Francisco.

The Roxie hosts a celebration of the book Sunday, May 28 and a retrospective of Baldwin’s films May 30–31. I met the Mission’s whirling dervish at his home base, the Artists’ Television Access space on Valencia St., for a typically chatty, digressive conversation. Baldwin greeted me with a lament about the current state of the building, where he’s screened thousands of alternative films since the ‘80s, and a brief history of the punk artists who preceded him.

Craig Baldwin: The history of this space [is that] it was too big — I think it was a bakery and a family could live here.

KQED Arts: A business in the front and the family lived upstairs.

I think it’s a brilliant idea. And you know what I call it? Live/work. [ATA and The Other] happened to be the destination space for people from the ‘burbs who would check this place out on a Saturday. You can’t get down the sidewalk. I’m not putting that down, by the way. I’m glad they come to the city. It’s too bad it doesn’t happen in their own neighborhoods but I’m glad to be presenting an alternative.

But we can hardly afford the rent. You know what’s two doors down? Dogue. If you want to serve your dog a $75 meal. Do you believe that? That is just m************ outrageous.

I’m here on account of Avant to Live, which has more love per page than the Kama Sutra.

I like that. The writers are pouring love on me, if that’s what you mean.

Do you recall a formative moment when motion pictures, moving images, captured you more than theater, sports writing and your other adolescent creative pursuits?

The first movie I ever saw, at the Village Theater when I was growing up in Sacramento. Lorna Doone. You could look it up. Black-and-white. Anyone can come up with an anecdote like that. There’s nothing particularly meaningful about that … that probably happens to every kid who goes to see their first movie. But I remember that moment to this day.

But that experience didn’t make you a filmmaker.

What made me a maker was Super 8. The generation coming up now, they don’t have their Super 8. It was the tractability, flexibility, mutability, portability, ease, comfort of Super 8 that anyone in high school would be doing.

You could borrow your best friend’s camera, or your parents might have a camera, and just go out and shoot. That’s probably it. But the found-footage thing, the Craig Baldwin thing, there is a story in the book about Stolen Movie, which is playing at the Roxie [May 30] and FlickSkin, the film that I made to get into the film program at [SF] State. I had my paintings in the Crocker Art Gallery in Sacramento. My mother probably sensed something, and she would drive me on a Saturday … many mothers do that, take their kids to art classes.

Then what made you different?

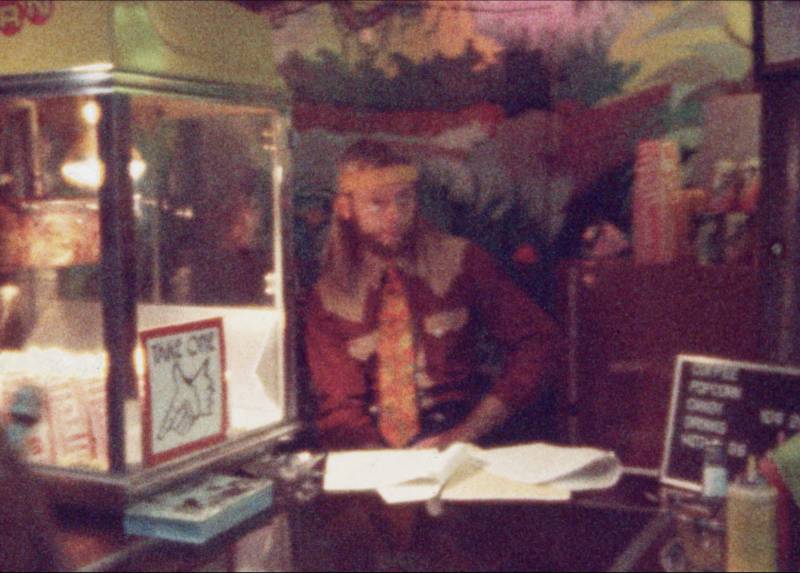

Good question. The subcultural thing [for one] … I was impoverished the whole time. I never went the pro route. Accident or nature or coincidence or God or whatever, I ended up having a roommate who had an uncle who ran a porn theater. I ended up sleeping in the projection booth. I saw what film was. Found film, to me —

That is, film intended for one purpose —

That I could re-use. But it was more the materiality. It could have been another way but I was in the porn field, I was close to the film, I was demystified, I was radicalized, I understood what it was, just light through a strip of celluloid. This was a public thing that people paid money to see, and it was nothing but that. And the way it was treated in that porn theater was not professional, you understand? It was devalued. It was degraded. It was the lowest, the gutter, and that’s what radicalized me. As a found-footage maker, I realized I could do that. For me, [film was] the artistic opportunity, the potential, the attraction, the allure, the eros, the desire to get your hands on it.

Anything else you recall about that porn house?

It was a very famous theater on the corner of Jones and Golden Gate. It was more like a pickup joint. People would just be standing, the screen would be there and people would be walking around. There were seats, but you weren’t expected to sit down. I said, ‘This is almost like an installation.’ Naïve, you understand. [I realized] film is not untouchable, film is not above me, not something I can’t reach. It is something at my level, it is free, cheap, like what I do here. [Baldwin waves his hand.] All these pieces of furniture were just found on the street. I wouldn’t buy a piece of furniture. It was just the way our generation lived. [Or at least] the way I did.

The tactile experience of shooting and editing film has been replaced by digital equipment. So what is the meaning of an image now? How does a 20-year-old maker connect with image-making, and does it matter?

I just don’t know. It’s a rhetorical question. It’s more difficult for me to personally connect, which has something to do with my generation, but also has to do with my sensibility, which is more like a sculptor or a painter. It’s more assemblage.

That’s why Bruce Conner connected with me. A Movie (Conner’s 1958 collage film that became a touchstone of experimental film) was part of an assemblage, part of an installation, of which there were a million things, the projector was part of it and the film was running on the projector. And he just said, “Let’s make this a standalone, let’s take the projector and the film and show it in a theater as opposed to a gallery.” That’s kind of an “aha” moment. Conner always identified himself as a sculptor, a visual artist. Moviemaker came way later in his career.

Viewers are somewhat more media-savvy than when you were editing shots from 1950s films into Tribulation 99 (1991). Do you think people trust images less than when you started out?

I never did trust it. I was always doing the fake news thing. Industrial films, educational films — for me the word is ideology. I was always trying to see through, X-ray, strip the whatever: capitalism, sexism, blah blah blah. I was radicalized. I happened to see the Bank of America burn in Isla Vista [in 1970] when I was 17 years old. I lived through it. For me, it was indulgent, silly, trivial to make films that weren’t addressing class war. That’s the dialectical materialism, that’s what you’re talking about. Class war almost seems like a quaint term, though I still believe in it. That’s what I’m still trying to get to.

One of the pieces in the book describes a lifestyle that you came to embrace called “masochism on the margins.”

I’m not saying I change the world, or culture jam. Not that there’s just two paths, but by engagement with the more corporate model, which is the larger model, that doesn’t necessarily guarantee that you are going to be able to make a difference, either. It’s a lose-lose situation, I guess you could say. So I choose the grind-me-up, self-sacrifice, marginal, the first guy they shoot kind of thing.

I always point to Jonas Salk, my hero. My father had polio. Big deal. He got through. And I did, because we had our polio shots. A small group of people can make a big difference. It’s not just elite people, like Salk certainly was. But people can propose ideas, and those people themselves might not be “successful,” but their ideas can live a little bit, down the line.

I learned from the book that you have a work in progress called Invisible Insurrection. What can you tell me about it?

I’m not very far along. I’ll finish that film. It’s all down there [points to the basement]. I just haven’t had the time. I’m just crying, screaming, raging overwhelmed right now. It’s a little bit of a review of a cultural history, and this moment where there was a resistance against the Bomb and then there was the move to suburbia, which I’m a product of, and then there were the beatniks, and so on.

What happened is, there are particular humans that we can point to and say, “Well, that guy had a pretty good idea what was going on,” and [one] was William Burroughs. Now, how many movies are there about William Burroughs? A lot. In France, the same postwar, the same malaise, “something’s wrong, something’s being screwed up.” The generation there that comes up, that’s the same as Burroughs, had their coterie of thinkers that we might call the Situationists. So it’s a Situationist film.

What happens is Burroughs shoots his wife, ends up in Africa, writes Naked Lunch, puts it together in Paris. Here’s Guy Debord, the guy who wrote The Society of the Spectacle (1967), which is also filled with quotes and aphorisms and citations — just like Burroughs. So these guys are developing a style which is a little bit reminiscent of everything we’ve been talking about today, which is this acknowledgement of philosophy and ideas that we have inherited that we think might be good, and putting together new combinations postwar, post-Bomb. They’re both writing [what] are arguably the most important books of our generation: Naked Lunch and The Society of the Spectacle.

What does your project do with those works?

What I am doing is having a conversation, a fistfight, between Burroughs and Debord, set in ’59 in France. I have a trillion French-language films, you understand. The right period, but also a little bit self-reflexive and hilarious. But I could use the voices of Debord and Burroughs. And I can certainly use the actual words, that is to say, what they wrote. Technology has provided that for us: You can get more text than you want.

So I can actually have those guys talking. I could recreate something that never happened. They never met. The point is I’m bringing them together. I will be able to have this discussion about intellectual history, about philosophical discourse, but in a para-narrative way. I [just] made that up. We see not only the discussion between Burroughs and Debord that never happened, but also the meeting of these two generations, the subcultures, the undergrounds, the progenitors of the ‘60s. Planting the seeds of resistance. A way of creating this moment postwar, our generation, in which these guys hash it out, in an essay form but not in a written linguistic form — in an enacted, embodied, imagistic form.

‘Craig Baldwin: Avant to Live!’ takes place May 28–31 at the Roxie Theater in San Francisco, kicking off with a book launch on May 28, screenings of Baldwin’s work May 30–31, and in-person appearances by the filmmaker at all events. Tickets and more info here.