Frisco Foodies is a recurring column in which a San Francisco local shares food memories of growing up in a now rapidly changing city.

S

an Francisco might not be known as a “sandwich town,” but hear me out: The City’s grab-and-go culture and proximity to fresh produce make it the perfect place for a one-handed meal.

Yes, you might associate us more with tourists eating clam chowder in a sourdough bread bowl, but one of the legacies of the Gold Rush and Frisco’s history of blue-collar laborers is that we hate sitting down for a meal, and we love taking it to go in the car — and finding a nice view to enjoy that sandwich while the fog rolls in. And with the advent of Dutch Crunch bread, invented in the Netherlands but a Bay Area specialty, our local sandwiches have an unparalleled layering of textures that can’t be found anywhere else. Did I mention how well they hold up to California avocados?

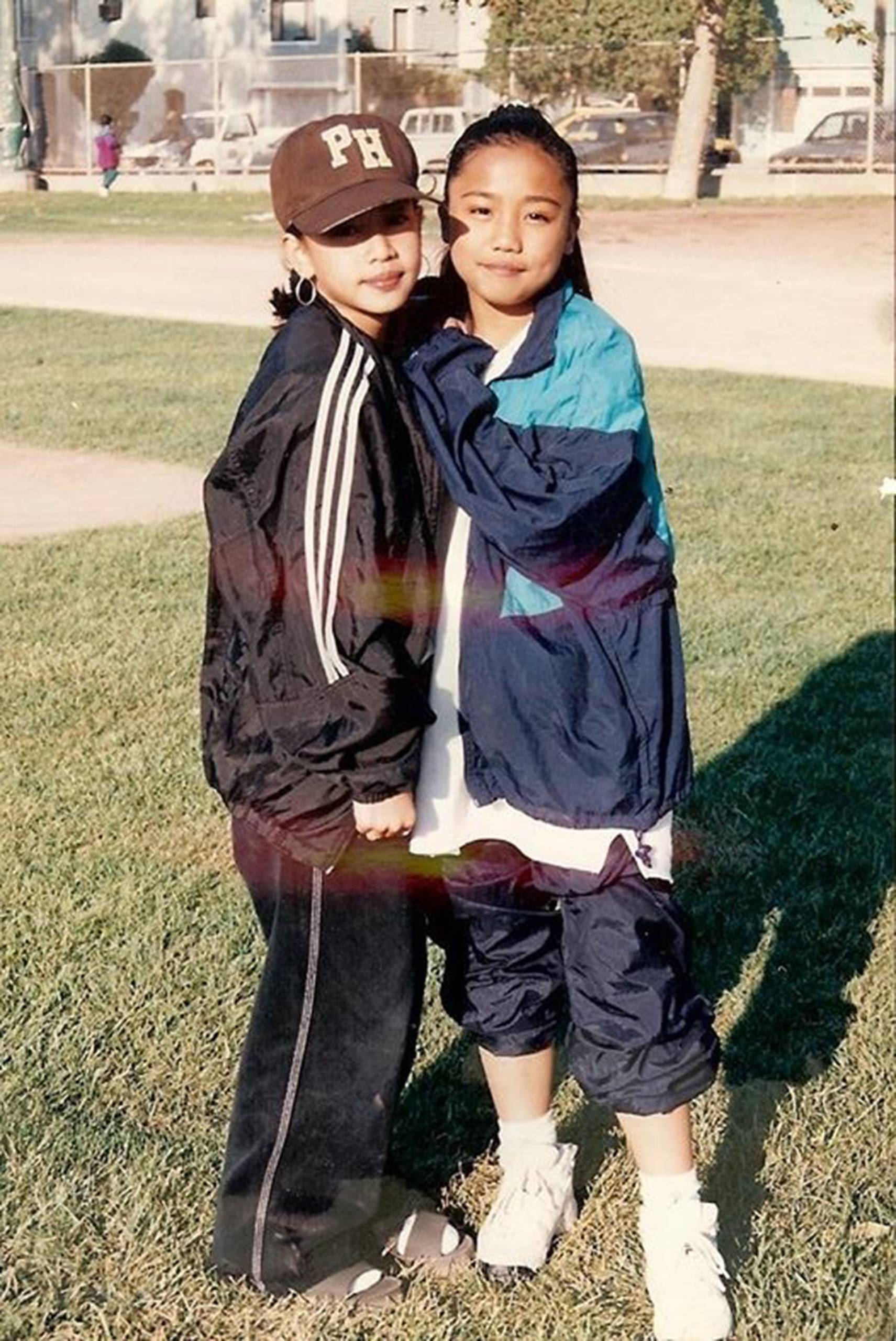

I was first introduced to the San Francisco-style deli sandwich at Jackson Park baseball field, where my best friend Arlene and I were the de facto softball managers for the Potrero Hill Middle School Stallions — a position we signed up for mostly just so we could leave class early. Once we set out the mitts and bases, Arlene and I would go around the corner to JB’s, where we split a roast beef on Dutch Crunch and a side of fries.

By the time practice was done, so were we. Stuffed and caught up on all the hot goss, we’d go back to Jackson Park, collect the mitts and bases, and do it all over again the next day. Those lazy afternoons of softball and sandwiches constituted an “America” we otherwise only saw in the movies. To me, they represented an idyllic time when families of color could still afford to live in the City, watch a game at Candlestick and truly feel like a part of the community. After we graduated, memories of our days on the bleachers faded, but my love for those SF-style deli sandwiches remained.