In her home office on the Peninsula, Senegalese fashion designer Diarra Bousso holds up a laptop, describing how she comes up with the prints that bring her DIARRABLU resort wear line to life.

“My process mostly starts from parametric equations,” Bousso says. “Like, you can either draw a circle or you can graph a circle.” Bousso prefers the latter.

As she talks, I get flashbacks of algebra class. (Bousso has also taught high school math; her lesson plans using fashion design are used by teachers across the country.)

“So this is like a sine polar curve, and it has variables called A and B. But just changing those variables, you get different shapes,” Bousso says as she uses the cursor to slide one variable’s tab to the right and a new pattern emerges.

Bousso screenshots the pattern in the Desmos graphing calculator app she’s been using and, seconds later, we’re in the prototyping phase. This involves a different, proprietary app. “I’m super proud of it. One of our engineers built it and I get to visualize what this [pattern] would look like on DIARRABLU pieces,” Bousso says, as the freshly designed print appears on a caftan silhouette, one of the line’s signature styles. “It’s all math.”

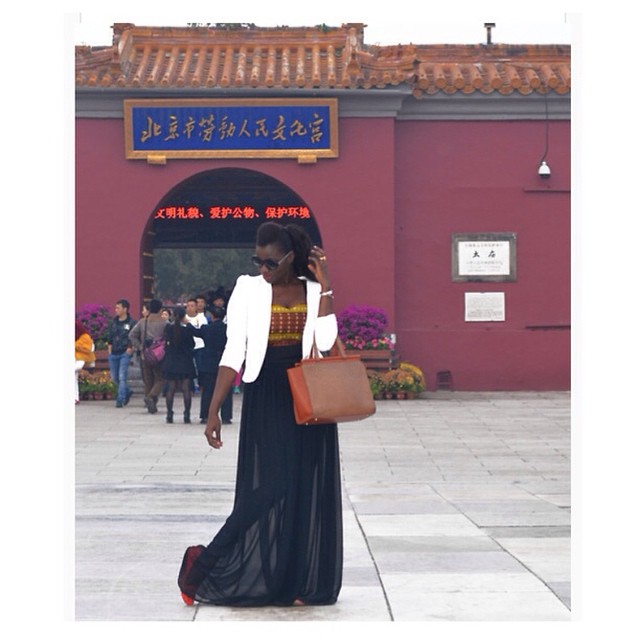

At 33, Bousso is certainly the sum of all her parts thus far: the mathematician, the artist, the designer, the traveler, the educator, the star student, the blogger. She’s also the survivor of a life-threatening accident that ultimately reset her life path. After years of doubting her artistic side in favor of pursuing a career in finance, Bousso has found her sweet spot as a “creative mathematician” — a title she learned about through one of her mentors, Stanford professor and author Jo Boaler.

When Bousso claimed that title, “it was like the first day I felt my identity had a niche. This is the name of what I’ve been doing my whole life, I just didn’t know.”

Math versus art

Bousso grew up in Dakar, Senegal, in what she calls a typical Senegalese family — her parents were very dedicated to her education. Her biggest inspiration, she says, is her father, El Hadji Amadou Gueye, who was the first person in his family to go to elementary school and later earned his MBA in France. Her mother, Khoudia Dionna, “was the best of her class,” Bousso says. “So she was all about academic excellence and she would be the one tutoring us after school.”

Bousso, who has two sisters, says she wasn’t very outgoing with other people, but “I was very talkative to myself. Like, I would have full on board meetings with myself in my room with different characters.”

Despite being a creative child, Bousso got the most praise in school for her math skills. In Senegal’s education system, after middle school, kids pick either a science track or a literature and social studies track; it was obvious for Bousso to go the science route, she says, “even though I wish they never did that separation.”

Being selected for national math competitions gave Bousso validation, and a sense of self: “Besides being a weird kid, I also could be a cool numbers kid, and I really liked that identity.”

Bousso’s GPA — one of the highest in the country at the time — got a teacher’s attention and, subsequently, a nomination to the United World College program in Norway, where Bousso spent her last two years of high school studying with teens from all over the world. She then received a full scholarship to Macalester University in Minnesota, where she studied math, economics and statistics — “the jobs my dad told me when I was 11 had a future,” Bousso recalls. Her creative side was still tugging on her, but she only casually indulged it. “I took some art classes on the side, but I didn’t feel confident, because I felt like I had real artists in my class and I thought I was a fake artist.”

All in on the numbers

In 2011, Bousso’s first job out of college was on Wall Street, trading mortgages.

“In my head I’m like, ‘oh my God, my family would be so proud. I’m in finance,’ which is what my dad did. Like, I’ve made it. Life is good,” Bousso remembers.

But within a few months, Bousso says the sparkle of her new life started to fade. On the weekends, she’d unleash her creative side, taking pictures of New York City life for a blog she started, then dread going back to work on Monday.

“And it slowly started getting deeper,” Bousso says. “I started asking myself very big existential questions, like, ‘What is the purpose of life? What am I here for?’ I got really depressed and I was very embarrassed about it because I [had] never failed.”