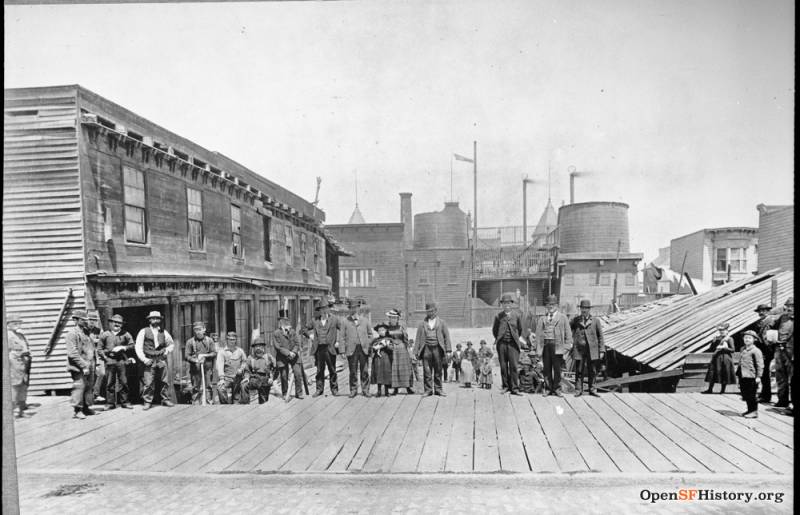

On June 1, 1884, Johnny Heinold handed over $100 and bought himself a salt-encrusted wooden shack at 50 Webster Street, on the Oakland waterfront. When Heinold first came upon the building, it was a lowly bunkhouse for oyster poachers, constructed out of old timbers from a shipwreck. Immediately, though, Heinold saw the building’s greater potential as a saloon. And he was right — Heinold’s First and Last Chance Saloon went on to become a legendary East Bay watering hole and, today, has more than earned its status as a National Historic Landmark.

When Heinold first opened the saloon, it was on the main highway between Oakland and Alameda. It was also located very close to the 1,000-foot-long Webster Street Bridge — then a major thoroughfare. The saloon was on the horse car line that ferried fans to and from baseball games at two different ballparks. Most importantly of all, 50 Webster Street was also surrounded by sea captains, sailors, fishermen and other dock workers who needed a drink or seven at the end of a long day.

It didn’t take long for Heinold’s First and Last Chance Saloon to become beloved by the community around it. The bar was also enormously profitable — Heinold is said to have averaged earnings of $40 a day at a time when $3 was considered a lot. But beyond the money, Heinold loved the saloon dearly for the rest of his life, spending most of his time behind the mahogany bar for close to half a century. In the end, he even died there — friends found him slumped over in a chair there one day in 1933, having suffered a stroke.

But oh, what a storied life Heinold and his saloon had before that. Here are five historical tidbits about both.

Jack London basically lived there

Heinold’s First and Last Chance Saloon’s biggest claim to fame, arguably, is being a major inspiration and favorite hangout of Jack London.