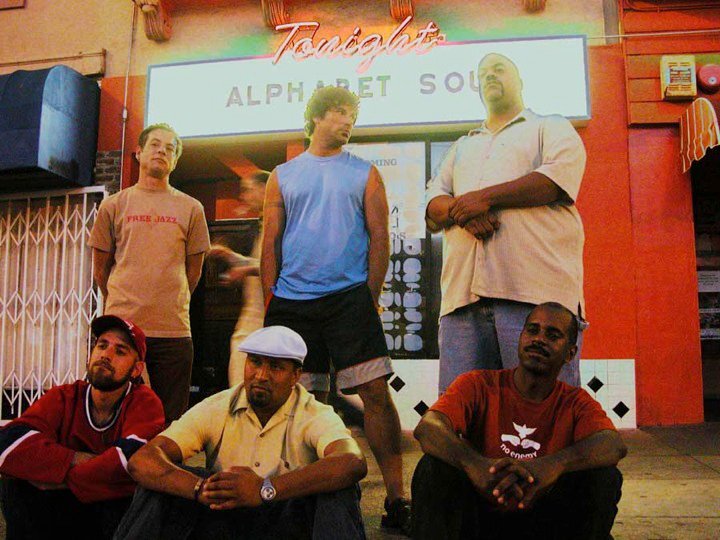

That guy was budding Berkeley impresario Gary Jones, who played an essential role in the formation and rise of Alphabet Soup. The group began to coalesce at a West Oakland gathering that brought Scott and Brooks together with Chris Burger, an omnivorously creative musician who’d been a track star at Berkeley High.

Rather than shedding influences as he rolled along in life, Burger added new sounds to his love of Jimi Hendrix and his infatuation with heavy metal. He’d caught the hip-hop bug seeing Run DMC on the 1984 Fresh Fest Tour at the Oakland Coliseum, and with his literary bent, he took to writing and honing his own rap verses.

The youngest of 10 kids with an older brother in and out of jail, Burger saw music as a path to avoid trouble. He started a rap group called Death Court at Berkeley High, “but my identity was a runner,” he says. “Thinking beats and rhythm helped me when I was running. It was really about pouring energy into rhythm.”

Burger’s manic intensity made that first encounter with Scott and Brooks potent, and the group’s early gigs brought bassist Arlington Houston and drummer Jay Lane into the Alphabet Soup pot. Scott soon realized his love of P-Funk drummer Jerome “Bigfoot” Brailey wasn’t what the situation called for, and Brooks supplied Scott with mixtapes to get him up to speed on hip-hop. As the group cohered, it rapidly established its innovative jazz and hip-hop-meets-East-Bay-grease sound on the burgeoning Mission District club scene.

Alphabet Soup wasn’t the only hip-hop group drawing on live jazz; A Tribe Called Quest set the standard for sampling jazz and deploying Ron Carter’s live bass with 1991’s The Low End Theory. But when Alphabet Soup shared bills with Us3, the British rap group known for sampling classic hard bop Blue Note tracks, they weren’t impressed. “We were like, you don’t have a band, you suck,” Scott says. “About that time, The Roots started to be known in Philly. They’d come out west and we’d get on bills with them, and that was cool.”

I

t was a heady time in San Francisco for a multiplicity of acts who reconfigured old and new idioms of Black American music. With labels like Ubiquity and its reissue-driven imprint Luv N’ Haight putting out tracks and albums, the overlapping groove scenes gained national traction.

In the Bay Area, the Mo’Fessionals earned an avid following by blending hip-hop, funk and R&B (featuring Chris Burger’s raps). But the 13-piece horn-driven combo made a bigger impression on the punk and new wave scene than in jazz and hip-hop.

Vocalist Lavay Smith and Her Red Hot Skillet Lickers turned Café du Nord into a jump blues joint, while guitarist Charlie Hunter brought low-down funk to the Elbo Room. Pianist Graham Connah turned Bruno’s into a protean jazz workshop with an array of ensembles, while vocalist Paula West started her rise to national prominence. Drummer Josh Jones brought a vivifying jolt of Afro-Cuban beats to the Up & Down Club on Folsom Street, which became ground zero for many of the era’s most exciting acts.

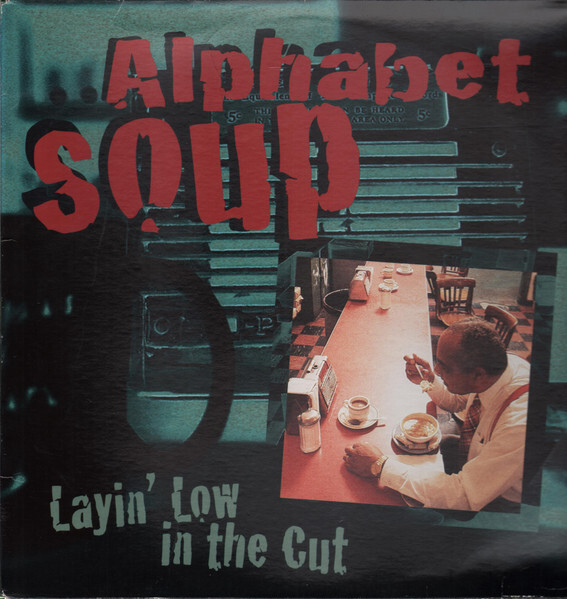

Two 1995 compilation albums released by Mammoth Records, Up & Down Club Sessions Vol. 1 & 2, captured this creative frisson with tracks by Alphabet Soup, Charlie Hunter, Kenny Brooks, Will Bernard, Josh Jones, Scheherazade Stone’s Hueman Flavor and the Eddie Marshall Hip-Hop Jazz Band, a group led by the veteran jazz drummer who’d played in the influential fusion band the Fourth Way a quarter century earlier (and served as unofficial house drummer at the 1970s North Beach jazz mecca Keystone Korner). Several members of the San Francisco 49ers frequented the club, which cross-pollinated its audiences as well as its musicians.

“I always thought that the hip-hop element turned that generation on to the jazz element,” says J.J. Morgan, who owned and ran the Up & Down Club from when it opened in 1992 until he sold it in 1997. “The hip-hop element made it the cool thing. With Alphabet Soup, the rapper didn’t come on until the second or third set. The first set was instrumental, so these 20-something kids are basically listening to this high-energy jazz. It was seven nights a week, but when you’re in it you don’t realize it’s special.”