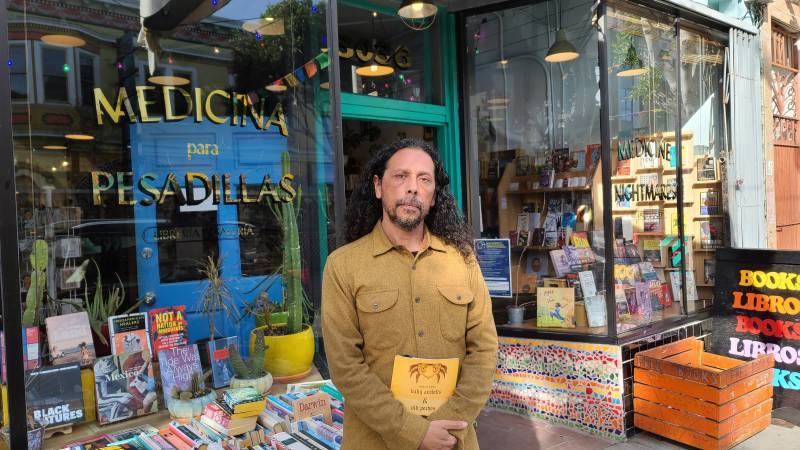

In a city that gives the cold shoulder to working class people and creative folks that aren’t backed by trust funds or tech money, Medicine for Nightmares Bookstore opens their doors to those who still care about the artistic soul of San Francisco.

It’s a place where you can walk in and be greeted with a warm “Hey hermano, hey prima, hey familia,” and strike up a conversation with the booksellers, fellow readers or local writers that frequent the Mission shop. It’s a venue where folks can read to a supportive inter generational audience. It’s a gallery space showcasing artists of color. It’s a sanctuary to just stop in and exhale a deep breath from the chaos of the city.

This familia vibe is tended to and nurtured by co-owner and poet Josiah Luis Alderete. Coming of age in San Francisco in the 90s, he became immersed in the Mission’s vibrant literary scene. “People say North Beach is the heart of a literary scene in San Pancho or in San Francisco, and I’d say, nah, man, it’s the Mission,” he muses.

As many of the bookstores and cafes from that era have shuttered in the neighborhood, Alderete is helping keep the Mission poetry scene alive through organizing and booking local writers to read and share their work at the 24th street bookstore.

In our conversation back in 2022, Josiah shared literary history of the Mission, why Axolotl’s show up in his pocho poems, and how his work is a form of memory keeping.

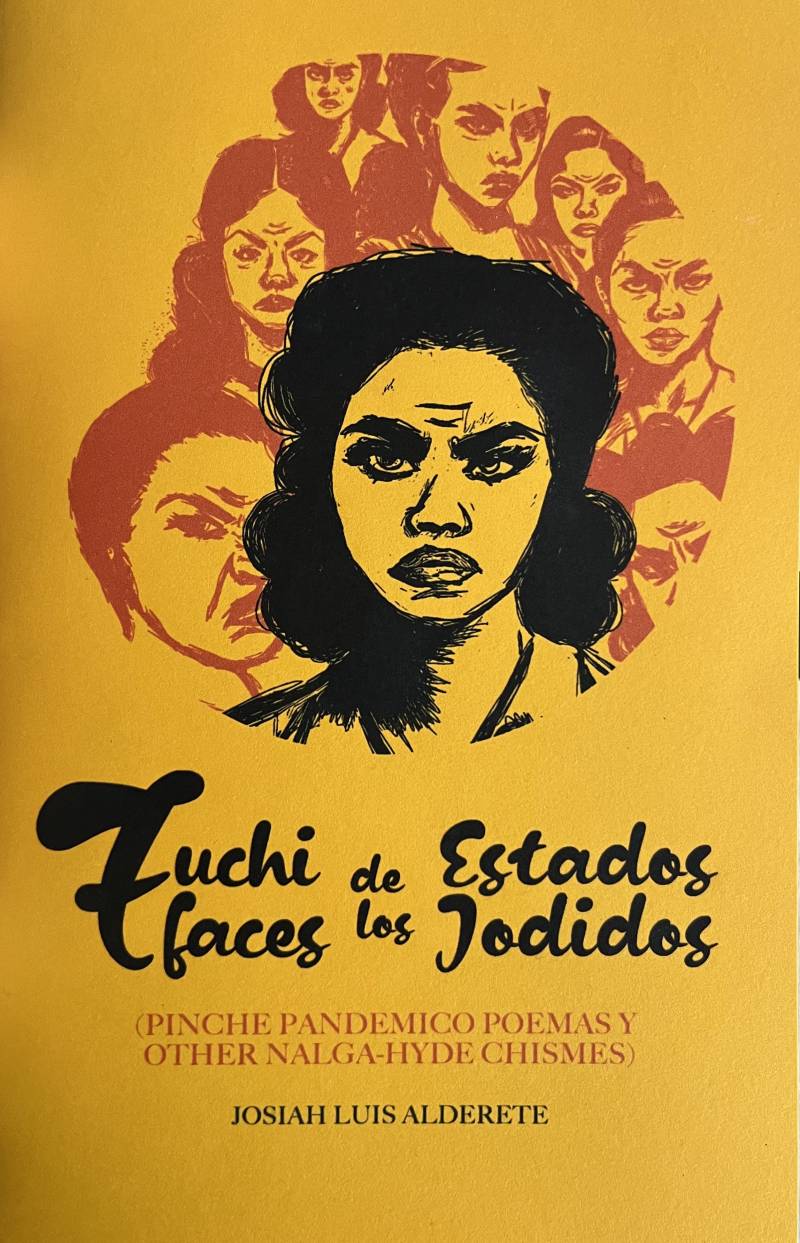

Most recently, Josiah published a new chapbook of poetry called Fuchi Faces de los Estados Jodidos. He has also been named the Fall 2023 Mazza Writer in Residence at San Francisco State’s Poetry Center. ¡Míralo, the poet stays busy poeting!

This fall, Medicine for Nightmares will celebrate its 2nd anniversary — a testament to the deep love and dedication that co-owners Alderete and Tân Khánh Cao have invested in the business despite the shaky pandemic economy. If you haven’t visited the store, do yourself a favor and check it out. It’s always filled with good energía and good people.

This episode originally aired March 4, 2022 .

Below are lightly edited excerpts of my conversation with Josiah Luis Alderete.

Marisol: On the cover [of your book] is a picture of a salamander indigenous to Mexico. It has the cute grin and the crown of feathery gills and in Nahuatl it’s called the “axolotl”… That’s also part of the name of your monthly poetry readings, Speaking Axolotl. I’d love to know what the axolotl symbolizes for you?

Josiah: The axolotl for me goes way back to my high school days. I went to a school that mostly only taught dead white males. So basically, I went to a very, very white school and never saw myself or my cultura in anything that was taught. That was the first place I was ever called a wetback. I remember that quite distinctly. I remember not knowing what it was. There were a lot of other words used there too.

But the last month before graduating, the English teacher gave us a short story to read called “Axolotl,” which is a story by Julio Cortazar. And I remember reading that story and connecting with it—Don’t get me wrong, I love reading other cultures, I love them dead white males, they’re great— but I looked [Cortazar] up right after that. I was like, ‘Quién? Who the hell is this?’

From Cortazar I found Márquez. From Márquez I found Borges. From Borges I found Silvina Ocampo. From Ocampo, Jimmy Santiago Baca. So it’s Julio that got me jumping off to those other people. So a lot of times when you see me using the axolotl, it’s kind of me giving a tribute back to Julio and that first moment when I connected as a youngster.

Marisol: Do the qualities of the axolotl — in that like they regenerate any time a limb is cut off or an organ is cut off — does any of that have resonance for you too?

Josiah: Oh yeah, when I realized that the reason we’ve discovered this is because there was some weird, nerdy dude in a science lab basically cutting off the little axolotl limb and he’s going, AHHHHH, (we can’t hear that) but [the limb] does come back, que no, it’s the resilience.

Marisol: You mentioning the fact that we know a lot about axolotls because like some scientist in the lab…I think that’s the strange paradox: the axolotl in Mexico are at the brink of extinction yet they’re like one of the most popular animals in research labs around the world. Maybe it’s also an allegory for like Latinx culture: it’s consumed but then [Latinx] people are barely hanging on here in the City.

Josiah: Yeah, that makes sense. That makes sense, that dissecting us. They’re always yanking things off, like, ‘What’s this taste like?’ [laughs], Yeah, man. That’s that’s a good one. I like that.

Marisol: In the spirit of having, community members come in and share their cuentos and their words [at Medicine for Nightmares] I want to have you read one of your poems from your book, Baby Axolotls & Old Pochos…

(untitled)

The rules for Español

en el caro or en la casa

the rules for Spanglish

near the front door or on certain playgrounds

the rules for English

near the Sizzler salad bar or when we talked about history

the rules for Nahuatl that I heard in mi dreams

pues no me acuerdo

mi accent goes way way back

and was not formed by the neighborhood I grew up in

or the place that mi familia is from

mi accent has been formed

by all those things about ourselves

that were not taught to us

by all those things that our ancestors were not allowed to say

mi accent has been formed by the forced violent migration

of our gente

by the mystical milagroso migration of our gente

along the way

along miles and years

between generations of talking blood and our children becoming our ancestors

we have peeled and transformed the idiomas that we have been given

so that we can believe what we are saying about ourselves

we’ve used what we’ve forgotten how to pronounce

without even knowing it

como constellations in el cielo

como slang directions to the party

como sagrado pronunciations of a ritual

como palabras that your abuelo spoke folded up in your corazon’s memorias

through no fault of our own mispronunciations

our tamales had one oliva each

with a hole in a hole in a hole

where what we were saying should have gone

cuando we were little

we spread the palabras out

on our Abuelita’s kitchen table

we’d mix the palabras up

with frijoles and tortillas that Abuelita would make for us

we could taste the history in what we were eating

we didn’t know what it was

we just knew it tasted good

that was when I learned

que the palabras that they give to us

no tienen sabor

the patron calls us another word for what we are

the religious man calls us another word for who we are

and so many of us end up believing them

si no los ponemos trucha

they’ll go ahead and lose us in-between the lines

they’ll go ahead and lose us in translation

¿can you pronounce yourself with the words that they have given you?

¿can you pronounce your cultura with the words that they have given you?

we can and do speak border because we have to

we can and do speak very clearly with our ancestor’s voices

I can speak just like mi Tia Vangie in a dream

I remember all of this

cuando I pronounce and mispronounce the palabras

Marisol: I picked that poem because I thought it spoke to this idea of identity formation and memory keeping, which I think a lot of your poems talk about. How do you see your poetry as a form of culture keeping?

Josiah: I mean, Black and brown poets, we’re historians. Art, for a lot of us, is all about survival and survival is history, is memoria. In a very small way my poesía is keeping track of us. Remembering the little things in the neighborhood.

Marisol: How do you think younger Josiah would feel about being here in the space as a co-owner alongside another poet [Tân Khánh Cao] owning a bookstore?

Josiah: It’s really silly, I always dreamed these dreams, but now that I’m doing it… like, how the hell did this happen? To flash forward and see the possibility that my book is going to be on the shelf and one of these strange, awkward little Latinx test tube babies is going to come in and pick it up and hopefully read something in there that connects ‘em… that’s a beautiful thing. If my poetry could do that to somebody, I think I got what I was supposed to do.

Rightnowish is an arts and culture podcast produced at KQED. Listen to it wherever you get your podcasts or click the play button at the top of this page and subscribe to the show on NPR One, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, TuneIn, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.