View the full episode transcript.

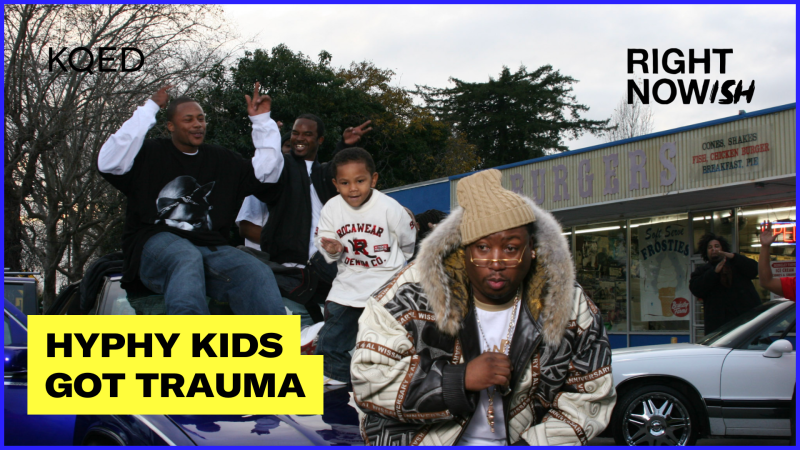

In the spring of 2006, I filmed and posted a video to Youth Radio’s YouTube page titled “Stomper Go Dumb.”

The video shows the Oakland A’s mascot, a big plush elephant in a baseball jersey and hat, dancing to a song titled “Happy To Be Here,” off of E-40’s My Ghetto Report Card album.

E-40 delivers lyrics that speak of surviving hard times and losing loved ones along the way. As the music plays, Stomper glides through the parking lot, dancing with the people, one with the letters “RIP” airbrushed on their shirt. A few folks hug each other and smile. This video clip, only a minute in length, is a window into a world where dance and jubilation meet mourning and sadness.

Before the “hyphy movement,” and even prior to having its own name, the style of dance now commonly known as turfin’ or turf dancing provided an outlet for young folks in Oakland. They could party to their favorite music, have fun by physically telling stories, and express themselves while taking up room on the floor.

Through appearances in big-time music videos and participation in dance battles at places like Deep East Oakland’s Youth Uprising Center, young folks not only got to show their moves — they were also able to honor their deceased loved ones.

In this episode, we talk to Jeriel Bey, the person credited with coining the term “turfin’,” Jacky Johnson, a founding Youth Uprising staff member, and Jesus El, my longtime friend and a well-known turf dancer.

Episode Transcript

Pendarvis Harshaw, Host: Heads up, this podcast contains explicit language.

In the spring of 2006, there was this video posted on Youtube titled “Stomper Go Dumb.”

[chatter, shouting, and cheering from the Stomper Go Dumb video]

The clip is less than a minute long, but it shows something that’s really important. It’s shot in a parking lot. It’s Stomper, the Oakland A’s mascot– a big gray plush elephant in white pants and a forest green and gold baseball jersey. And he’s out there giggin’ to an E-40 song. Ears flapping, feet sliding, arms waving, Stomper is in full party mode, and so are the folks around him.

Behind the camera is me. In the footage, Stomper gets close to the camera, daps me up, then he proceeds to glide across the pavement, pausing momentarily to act as if he’s ghostriding the whip, and then he thizz dances. Another guy in an airbrushed white-t stands next to him, giggin’ as well.

The guy’s shirt has the letters RIP boldly written next to an illegible name. And they’re all dancing to E-40’s “Happy to Be Here.”

[Happy to be Here by E-40 plays]

Pendarvis Harshaw: The track is off of 40’s My Ghetto Report Card album, one of the few slower tracks off of his landmark project, which is chock full of high energy party anthems.

But in that moment, as we’re posted in front of E-40’s album release party at Tower Records, it’s this song that plays as the A’s mascot is showing off his gigs.

People are dancing and laughing, embracing each other and celebrating, despite having the letters RIP and their friends’ names written across their chest.

[Happy to be Here by E-40 fades in]

“Oooh; it’s gloomy out here, dark days ahead

God got my back but the devil he want my head”

Pendarvis Harshaw: After I shot the video, I posted it to the YouTube page for Youth Radio, now known as YR Media. I was a baby reporter working with them at the time.

And with this video racking up half a million views, and hella people using this footage as GIFs on social media platforms, it was clear that I’d documented something significant.

Deeper than a dancing elephant, it was a window into the culture. I’m Pendarvis Harshaw, and this is Hyphy Kids Got Trauma.

[Music]

Pendarvis Harshaw: In that video of Stomper dancing to an E-40 song, the mascot does a few more dance moves, and then gives an extended embrace to a brotha with cornrows in a black leather jacket. The person inside the Stomper mascot outfit is saying what’s up to my right hand man, Jesus El, Zeus as we call him.

He’s just a couple inches taller than me, born exactly three weeks before me, and we’re a lot alike. We’re socialites; neither of us can stay away from a party. Oakland proud, we both love the town and constantly get caught up in our own thoughts about how to save it – and the world, for that matter.

While I chose to sit down and write for a living, Zeus chose to fly. A trained gymnast, for over a decade he worked for the NBA, majority of that time was with the Golden State Warriors as an acro-dunker.

[hip-hop music echoes inside of stadium with a cheering crowd]

Pendarvis Harshaw: That means that at halftime of a game he’d come out with his crew – the Warriors’ Team Thunder dunk team – and run across the court, bounce off a trampoline, elevate higher than the rim, catch the ball mid-air, wink at the camera, and then dunk the ball before safely returning to earth. Outside of that, he’s also a well-known dancer from West Oakland.

[Music]

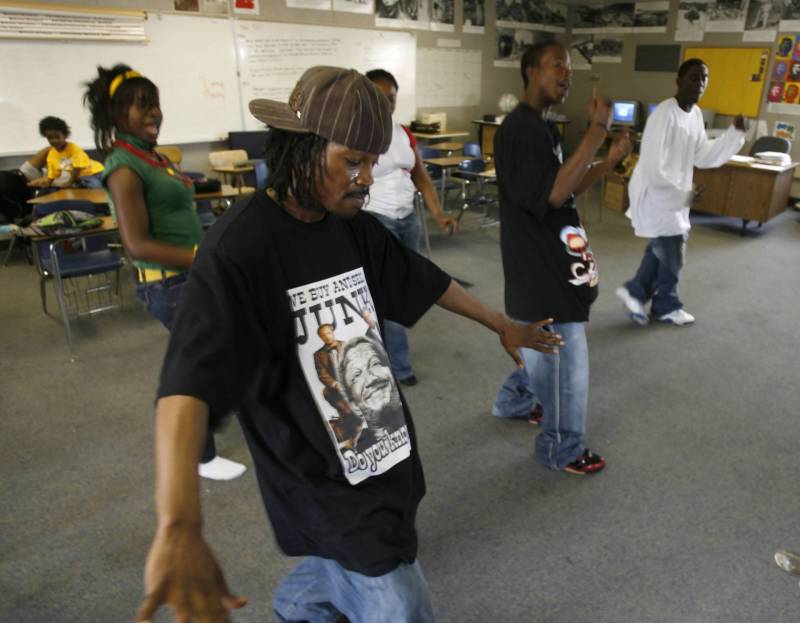

Pendarvis Harshaw: I got this photo in my text message today. What’s going on here?

Jesus El, guest: Oh, man, that’s crazy. That’s a throwback. So this photo is of me dancing at Youth Uprising in a dance battle. Uh, and I look super young and skinny.

Pendarvis Harshaw: We grew up in different parts of the Town, and met during a 7th grade summer program– cracking jokes on the back of the bus. And after twenty-plus years, we haven’t stopped cracking jokes since.

Pendarvis Harshaw: The jordans – are those the fake Jordans we got?

Jesus El: I think those was the fake Jordans.

Pendarvis Harshaw: The fake Jordans.

Jesus El: Yours was fakers than mine though.

Pendarvis Harshaw: Faker? How they– if they fake, they fake.

Jesus El: If they fake they fake, but yours… your Jordan had buttcheeks. Remember that?

Pendarvis Harshaw: He was facing the wrong way.

Jesus El: He was facing the wrong way and he had the buttcheeks showing. Mine, I could at least, you know, well I was getting away with it.

Pendarvis Harshaw: You just gotta pull the jeans down.

Jesus El: I had to pull the jeans– yeah, I had to wear the big jeans over him.

[Music]

Pendarvis Harshaw: Back in ‘06 we were broke community college students taking classes at Laney in Oakland.

Zeus had dreams of becoming an NBA mascot, and was simultaneously developing his own acro-dunking team. I was focused on doing journalism, and had just got accepted to Howard University.

So while I was spending the year getting ready for college on the east coast and getting my journalism chops up, Zeus was building his own legacy, both in the Town and around the globe.

Jesus El: I’ve been to China ten times, been to Italy, um, Rome, Japan, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Mexico…

Pendarvis Harshaw: He adds England, Budapest, and all of North America. He’s performed for Ripley’s Believe It or Not, holds a couple Guinness World Records, and in 2005 he performed in front of some of the biggest names in the business at the NBA All Star game in Denver, Colorado.

Jesus El: I met Destiny’s Child. They like, room was right next door to ours. Jay-Z, Chris Tucker, we met so many different people…

Pendarvis Harshaw: Zeus got his start after being mentored by the late Sadiki Fuller, the guy who wore the Thunder mascot costume for the Golden State Warriors. And that’s how Zeus got to know other mascots– like Stomper.

But Zeus’ main inspiration came from superheroes in movies and television shows. In his own way, Zeus was a superhero when he was on the court. And just like any superhero, he’d be treated differently when he took the cape, or um, uniform off. He would leave the old Warriors arena in East Oakland and he’d transition, like Superman to Clark Kent.

Jesus El: I had times where I’m having the day of my life. Like, I just did a new dunk, I’m the first person to do it. I do it in front of people. I make it. I’m feeling like on cloud nine…

[Music]

Jesus El: …and then I get back, you know everybody leaving the BART, and uh people don’t have to notice me—I’m not tripping off of that. But then, you know, people clutching they purse or, you know, like, just trying to, like, stand away from me, you know what I mean. I’m like, bruh, you was just clapping for me.

Pendarvis Harshaw: Yeah

Jesus El: Just like that, you was just clapping for me, and now I’m just another nigga that may bring harm your way and that’s trauma within itself.

Pendarvis Harshaw: There’s trauma in that duality of physically showing joy, and being celebrated and then getting hit with the weight of reality.

In order to escape it, Zeus would literally leave. He found solace in seeing the world. But despite the freedom he felt traveling back then, Zeus knew he had to keep his stories close to the chest because of how smirkish people can be.

Jesus El: I remember just traveling like, I mean, soon as, aw man, soon as I touch that airplane: Oakland is in Oakland. I’m going global, I’m out. Right? And then when I come home, I have to pretend like I’m not that person.

Pendarvis Harshaw: You gotta dumb it down?

Jesus El: I gotta dumb it down all the time. Because, one, people… people who speak too highly of themselves are typically the ones who end up shot first, right?

They typically the ones that people target. It could be jealousy. It could be hate. It could be all kind of stuff. But people who… sometimes you got to just stay under the radar to survive. That’s how we survived this long.

Pendarvis Harshaw: As confining as that might seem, it was kind of the code, still is. The Town is a place where you gotta stay low even as you come up.

But on the contrary, Zeus was getting his limelight on the hoop courts. And outside of that, he was cutting up on the dancefloor– that’s where he really escaped, specifically, through the art of turf dancing.

Jesus El: Turf Dancing is an acronym called Taking Up Room on the Floor that was coined by Jeriel Bey.

So turf dancing, it’s a style of dance that derives from Oakland. And it’s storytelling and it’s certain moves that you do, but it’s storytelling. It’s waving, gliding, all of that but it’s a certain swag that comes with it.

But before it was even called turfing, it was called hitting it or touching it or fucking wit it. Like, ‘fuck wit it bruh’, ya know what im saying?

[Music]

Pendarvis Harshaw: Jeriel Bey, raised between Oakland and LA, is a marketing minded brother who had turf dancing, lightweight, land on his doorstep.

Jeriel Bey, guest: They know me as the godfather of turf dancing. I coined the phrase, a lot of people are like ‘you didn’t coin the phrase!’ But you know coining is something you use before anybody else use it. So I used it in both, in print and on my fliers, you know, my events, you know, just… I knew long ago just from having a lot of internships that, you know, you brand yourself, you know how to brand myself. So I definitely am known for that.

Pendarvis Harshaw: Jeriel was a party promoter, who was living in West Oakland and that’s where, two young dudes from the neighborhood, Demtrius Zeigler and Cory Johnson AKA Scooby, would hang around his house.

Jeriel Bey: Those are the two first kids I met and then those two kids brought every other kid around me. You know, these kids, like, 14, 15, with sawed off shotguns in their backpacks. Like, bad but good kids, they just needed some focus. And the only thing they all knew that they all knew how to do was dance. Guns, and money, drugs and all, they all was coming in front of the house, dancing with me. And so my thing was like, okay, I got to give back and give ’em something to do.

Pendarvis Harshaw: The dance sessions brought about dope moves, clean gigs and hyped reactions. The problem was: the dance they were doing didn’t really have a name. There were notable moves: the drop, the airwalk, the old school Brookfield. But the overall dance style was kinda just a part of Oakland culture. That’s how we moved.

And, at the same time, the terms folks were using to describe the dance style weren’t exactly marketable to the venues Jeriel was looking to work with.

Jeriel Bey: I was like man, I can’t sell this as ‘fucking with it’ or ‘giggin’.

Pendarvis Harshaw: So Jeriel started brainstorming, and during a conversation with one of his cousins, it all clicked.

Jeriel Bey: Man, I got these youngstas in front of the house, you remember Demetrius and Scooby? They be ‘fuckin wit it’ and shit, you know, they all be dance differently: the East Oakland, the West Oakland, you know? They all dance different. Like I said, like different turfs and they all dance different…Man, how does turf dancing sound? He was like, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s it. That’s, that’s it right there!’

And so that’s what it was. Everywhere the little homies was going, ‘What ya’ll doing?’ We turf dancing, we turf dancing. And that’s how it stuck. Even when I did community events in the City, I made sure they put it on the fliers, we turf dancing. We’re not “hyphy dancers,” hyphy was kind of like the energy, the spirit, the movement. But, you know, turfing is how we was able to separate ourselves from the energy, you know, we was turf dancing. We wasn’t hyphy dancing.

Pendarvis Harshaw: Turf dancing – a mixture of boogaloo, poplock, pantomime, and being player while moving on beat – was something different than just going 18 dummy like some might imagine when we’re talking “hyphy” dancing. I mean, that was a part of it, but it was deeper than just shaking yo’ dreads.

[Echo of E-40 saying “Shake them dreads.”]

[Music]

Pendarvis Harshaw: It was a world of Bay Area storytelling through dance, complete with signature moves from certain neighborhoods. Hence the name “turf” dancing.

And people would dance everywhere, at the bus stop, the house party, The candy shop – which was this fake-teenager-club-function thing that didn’t serve alcohol but was somehow still full of faded teenagers.

We hit it at the sideshow, on a car, in a car. In the school hallway, acting as if you were a car. And, at your local community center, specifically this one called Youth Uprising.

When Youth Uprising opened in 2005, it was this sleek looking youth center located on 87th and MacArthur in East Oakland.

[Music]

Pendarvis Harshaw: A huge-freshly painted state of the art building with bright colors that stood in contrast to the surrounding apartment buildings and the adjacent school – Castlemont High School– an institution that had been under-resourced for years, and it showed.

Inside of Youth Uprising, the building was well-decorated with artwork and photos. They offered healthy meals to teenagers who came from the surrounding community, as well as employment and educational resources.

I’d go up there and kick it in the music studios or attend discussions about the state of the community. And I’d also hit the dance battles they threw– turf dance battles. Here’s founding Youth Uprising staff member Jacky Johnson.

[Music]

Jacky Johnson, guest: We stopped publicizing them after a while. We would just like announce the day of we were gonna do it because they would just get so like crazy. Like, our little amphitheater would just be packed. And we would see, like, young people running down the hill across MacArthur from, um, up the hill just run cutting through like, backyards to run over to the center.

Pendarvis Harshaw: Jacky is a longtime community advocate who works at the intersection of social justice and entertainment.

Back in the day, she got her start as a young adult on the staff of Youth Uprising. One of her tasks was to organize and promote the turf dance battle events. And through that, she saw how important dancing was to the culture.

Jacky Johnson: The crowd fueled the dancers. The dancers fueled the crowd. Like it was just this perfect mixture of just a showing of what, um, Oakland, of what the Bay Area’s energy is about. And I just think of that time, I always reflect on, you can’t, you know, I, I hope that young people or, you know, other generations, they’ll have their own moments like that, but that, to me, that just feels like a moment that couldn’t… couldn’t be duplicated.

Pendarvis Harshaw: The dance battles would be roughly once a month, and they’d garner all kinds of attention. Makes sense, we didn’t have much else to do.

A lot of this culture was born out of a void. There weren’t many places in Oakland where folks could congregate for large scale-hip-hop events, and it had been that way. Because of previous conflicts and altercations at shows, hip-hop concerts were constantly under threat of being banned or over-policed in Oakland.

A lot of artists and promoters would turn to the Bay Area suburbs and central valley to do hip-hop events. But Youth Uprising was one of the venues in Oakland working to connect young fans to the local stars.

Jacky Johnson: A lot of artists would stop through and perform, and I think they loved being able to connect with the young people and be a source of inspiration. And then the young people were excited because they never knew who was gonna stop by and what was gonna happen next.

[Music]

Pendarvis Harshaw: Yeah, that was me, one of the young folks juiced to be at the center.

I initially started by catching the bus up there after hearing about it from friends. But when I got my car, this plum colored Chrysler Sebring with a functional sunroof and dysfunctional sound system, I was there. Well, until the transmission died, then I was back on the bus. But either way, I was fasho pulling up.

And I’d bounce out with the same camcorder I filmed Stomper going dumb with, show love to the security guards, and then, as a young journalist trying to get on, I’d find my way to interviewing folks like E-40, Mistah FAB, Vidal White, Too $hort, The Husalah, The Jacka and later, Oakland Mayor Ron Dellums. I have a few photos from back then, not much video.

When I look back at the few photos I have of myself from back then? Man, I was in it!

Specifically this one photo of me sitting in the audience of a dance battle, wearing an oversized t-shirt, baggy jeans, and those knock off Jordans that Zeus roasted me about, while holding on to that camcorder.

Yeah, I was in it.

I was one of the many young folks who ascribed to a culture that was having its moment in the sun, despite the ever-present dark clouds.

Back in the day, Jeriel Bey taught classes at Youth Uprising. In addition to that, he choreographed dances for music videos and performances. He also threw dance events–including battles between cities.

Right before one event in Los Angeles, Demetrius Zigler, who used to hang out in front of Jeriel’s house, was killed. In response, Jeriel and his dance team, the Architeckz, danced in the battle in Demetrius’ honor.

[Music]

Jeriel Bey: I remember us all having this sweater, his picture, like, you know, on the hoodies, which is synonymous with losing someone on the street. So we had him on our hoodies. We drove down to L.A.

Pendarvis Harshaw: Jeriel and his team won the battle, but they did so while mourning their friend. Full of mixed emotions, they made the drive back to Northern California.

Jeriel Bey: I’m tired, everybody is sleep in the van. I get a call, I think, from Jacky Johnson. She’s like, ‘Yeah, you know, E-40 heard about your guy being killed, and um and they want to put you on this video called, Tell Me When to Go.’

[Record scratch]

Jeriel Bey: I said, the song I’d been hearing on the Radio? She goes ‘Yeah. They’re shooting in West Oakland right now.’ I’m like, damn, I live in West Oakland like we’re all by the train station. What? That’s three blocks away from me.

[Music]

Jeriel Bey: Cool. I wake up everybody, I’m like a man we finna go shoot a video. ‘What video?’ Tell Me When to Go. ‘What?!’ We smash to West Oakland, we pull up to the house, we take a little hoe baths and shit, wash our faces and shit.

Pendarvis Harshaw: They get to the set, and 40, Lil Jon and the production team are moving through scenes. The iconic opening of the video, with a circle of folks going dumb on the ground shaking their dreads? That’s not them. That’s another dance crew.

After rushing to the set, rehearsing an impromptu routine and getting ready for their light, Jeriel and the Architeckz almost get skipped over.

Jeriel Bey: And they was like ‘We gon’ give you one shot, let me see what y’all got.’ And then the rest is history.

Pendarvis Harshaw: The black and white footage from the video shows the group forming a semicircle, with the opening facing the camera. They dance aggressively, hittin’ signature turf dance moves as well as shaking their dreads. The majority of them are wearing the hoodies dedicated to Demetrius. Dancing in his honor, they left an impression on the filmmakers.

Jeriel Bey: We shot like three more times after that. And before the video came out, it was, ‘Oh, good job, Architects,’ oh, E-40, people loved us, ‘Oh, ‘Demetrius, rest in peace, Demetrius, aww community community,’ but as soon as that muthafucka hit MTV, it was like, ‘Man them niggas ain’t really from Oakland tho.’ It’s all the hate and then the bullshit came.

Pendarvis Harshaw: People were congratulating them on the video set, but were critical once the video came out. Jeriel says that other artists, dancers and people from the Bay Area hip-hop community made comments about the fact that Jeriel is originally from LA, or that the Architeckz weren’t that tight. Jeriel was shocked.

Jeriel Bey: That’s when I realized, like, yo, people can love you on the way up, but the envy is a muthafucka. Envy will get you killed out here when people feel like they deserve more than you and I experienced all that shit.

Pendarvis Harshaw: Jeriel says people were envious of the Architeckz success.

And, really it was misguided anger – a byproduct of the lack of resources. If there were more limelight, everyone could shine.

[Music]

Pendarvis Harshaw: But that video being on MTV, and the media attention that was focused on the hoods of the Bay Area during the Hyphy Movement came on the heels of years of media neglect. So folks were hungry, vying for an opening.

Some artists were over-promoting this hyphy thing. A few big media platforms, clothing lines, club promoters, even community centers were selling it.

Here’s Zeus.

Jesus El: Man, to be honest with you, I don’t think Youth Uprising would have been that impactful if it wasn’t for the dance culture, because a lot of people were showing up for the dance culture and staying for the resources, you know what I mean?

Pendarvis Harshaw: Jacky saw it differently, and has the same sentiments as Zeus. After the dance battles, how do you connect folks with counseling, healthcare and other resources?

Jacky Johnson: We’re like, okay, well how do we move these young people into our programming? And that would sometimes be a challenge because I think sometimes we felt really- I felt for sure stressed out about like, okay, like are we doing enough if they’re coming here and they’re not going into a, you know, career and education program.

Pendarvis Harshaw: The whole situation made Jacky frustrated.

Jacky Johnson: You have to hit these deliverables. It’s like, how do you, like, okay, you get this amount of money now go and transform somebody’s life as they’ve, yeah, experienced all this trauma and need all of the- these things, or the fact that we all are going through our own shit.

Pendarvis Harshaw: The Youth Uprising center has gone through its ups and downs, but it still stands today. And back when it first opened, even with all of the elements at play, the center was a beacon for kids like me and Zeus.

[Music]

[crowd cheering]

Jesus El: We on the bus, catching the 57 from West Oakland all the way to 88 and MacArthur, and this is when it was super turfed out. I’m talking about real hood, so we up there battling cats, Like around the stage it was like 300 people, like hanging over, just having hella fun tho. But you would have different people from different sides of the city come out and battle each other. And that’s how you earned your respect. Like with dancing, you earn your respect because you’re way somewhere in somebody else’s hood, and you could be battling they friend. But if you raw, they gon be like you raw bruh. Like I still know people to this day from me meeting them at Youth Uprising.

Pendarvis Harshaw: Those experiences. That community. Those intangibles. They don’t show up in a fiscal report. They show up in people’s memories.

I have mental pictures of audiences going wild after someone hit a backflip during a dance battle, fond memories of meeting a new crush after the conclusion of an event. And I even have one picture from that day that E-40 pulled up for a photo shoot.

Jacky Johnson: We really wanted to create a safe space from the violence, safe space from the police, um, where we kind of held it down and it was just this raw energy.

[Music]

Pendarvis Harshaw: Youth Uprising was one of the many nonprofits that both invested in, and benefited from the culture.

Its location, resources, and connections to big name-artists made it significant. But the youth programs, they were just a Band-Aid in the face of generations of neglected neighborhoods and people living in poverty.

The trauma that we inherited existed long before we did, and still, we found joy in the middle of all that. Some of the moments turned into photos, others are invisible memories that are stories waiting to be told.

And the stories – the way they were told, who told them and what stories were not told – well that’s another layer to the trauma. We’ll get into all of that in the next episode.

Seaside Stretch, guest: Just the term “hyphy,” was, it meant something completely different to what it was commercialized as. You know what I mean? It it wasn’t a good thing, you know what I’m saying? Like, they didn’t say like, Oh, them kids is hyphy, and that meant that they were just dancing around having a good time. No, that means that they were destructive and violent, you know?

Pendarvis Harshaw: This is Hyphy kids Got Trauma.

Hosted by me, Pendarvis Harshaw

Produced by Maya Cueva

Edited by Chris Hambrick

Sound design and original music by Trackademics

With support from Eric Arnold, Jen Chien, Holly Kernan, Victoria Mauleon, Marisol Medina-Cadena, Gabe Meline, Xorje Olivares, Delency Parham, Cesar Saldaña, Sayre Quevedo, Katie Sprenger, Nastia Voynovskaya, and Ryce Stoughtenborough.

This project was produced with support from PRX and is made possible, in part, by a grant from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

And this is a part of KQED’s That’s My Word project, a year-long exploration of Bay Area Hip-Hop history. Find more at BayAreaHipHop.Com

RIP Demtrius Zigler, and so many more.

Until next time, peace.

Rightnowish is an arts and culture podcast produced at KQED. Listen to it wherever you get your podcasts or click the play button at the top of this page and subscribe to the show on NPR One, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, TuneIn, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.