Though Topless at the Condor does its best to explore whether Doda’s decision to take it all off could be considered a feminist act, the issue is far too complex for the film’s soundbites. Within Doda’s story, there are seeds of joy: bold women exercising the freedom to show off whatever body parts they wanted. The film attempts to draw a parallel between second-wave feminists who burned their bras and Doda’s decision to free her nipples. But this point is a stretch, at best.

In another line of argument, the film weighs dancers’ individual financial gains against the collective effects of normalized objectification. Unfortunately, despite some solid input from commentators like Wednesday Martin and Florence Williams, there simply isn’t enough time here to effectively unpack questions of empowerment and exploitation.

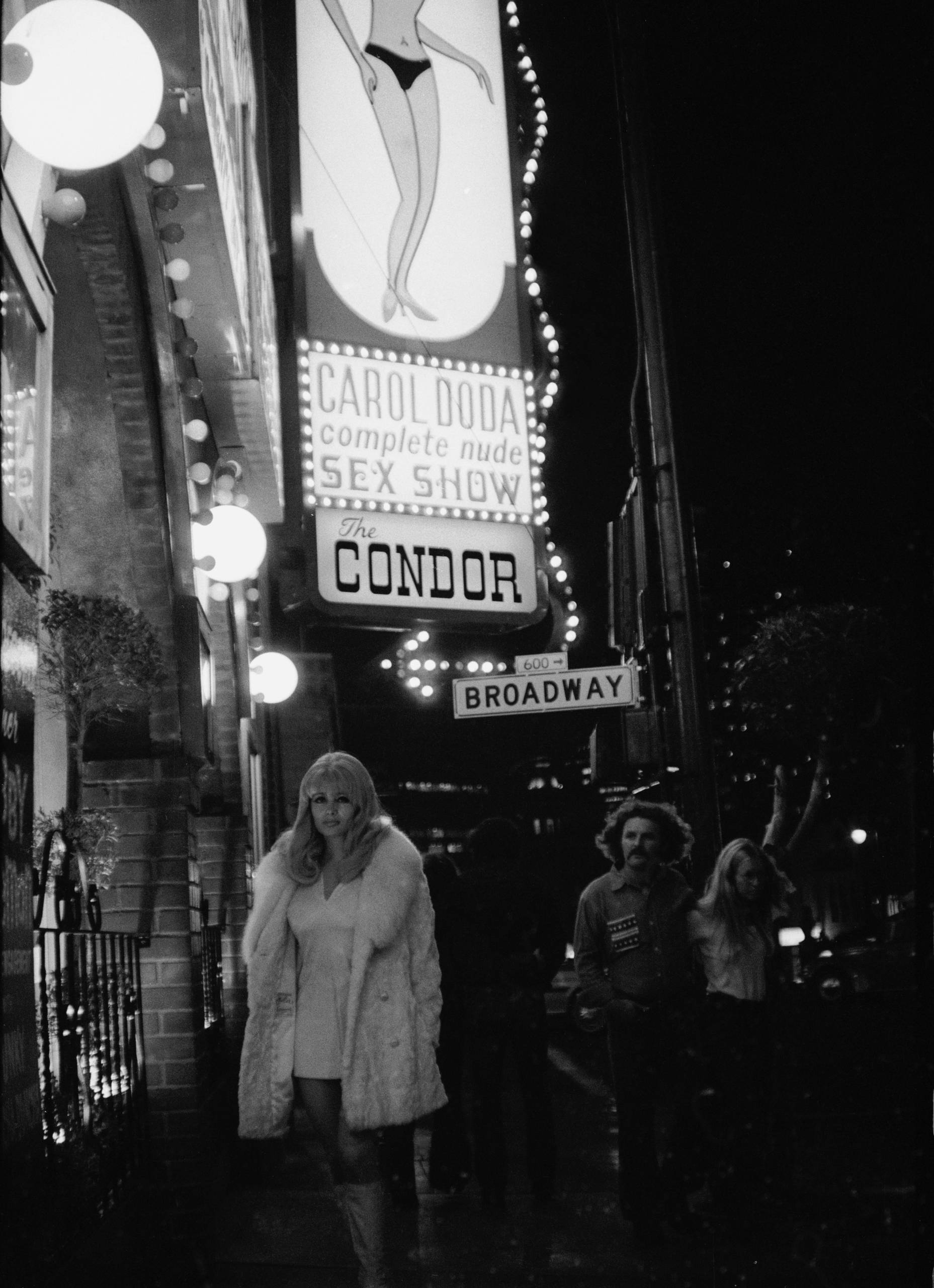

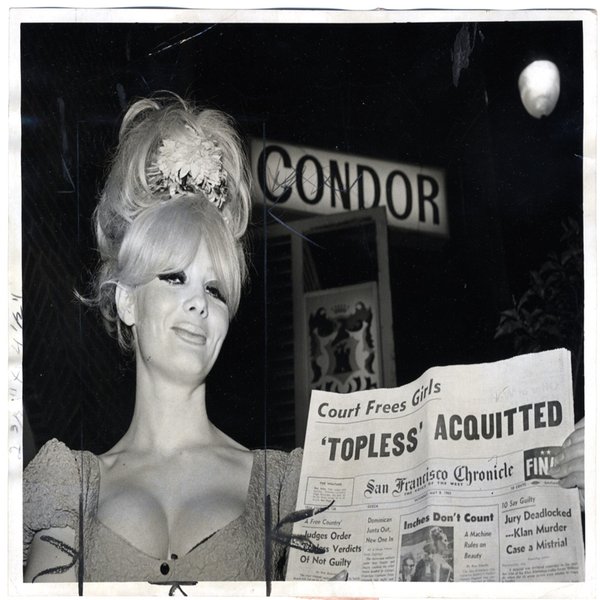

What the film does more successfully is transport the audience back to the sights, sounds, lights and music of 1960s North Beach. Sly Stone’s history in the neighborhood is a welcome addition to the narrative, as is the music of Teddy & George. The documentary is also outstanding when it comes to exploring Doda’s moxie, personal motivations and drive to survive. Some of the nuggets uncovered here about Doda’s later life — like the fact that she performed with a metal band at the DNA Lounge in the 1980s — are captivating. Any time interview footage of Doda is used, her charisma and complexity shine through.

Doda was a product of her time and circumstances and she paid dearly for both her boundary-pushing and endearing, devil-may-care attitude. The film works hard over its 100 minutes to pay Doda her dues and immortalize her life and legacy in a meaningful way. But, like so many who flocked to North Beach in the ’60s in search of a good time, viewers of Carol Doda: Topless at the Condor might be surprised to find out just how much grime was lurking underneath all of that glitz.

‘Carol Doda: Topless at the Condor’ opens at San Francisco’s Roxie Theater (3117 16th St.) and San Rafael’s Smith Rafael Film Center (1118 4th St.) on March 22, 2024. The documentary expands to screens nationwide on March 29.