At one point far into Maurice Vellekoop’s operatic, nearly 500-page graphic memoir I’m So Glad We Had This Time Together, he depicts himself at an art event in Toronto. He has donated his work to the silent auction and is now scoping out the scene, chatting up yet another handsome stranger in search of that elusive spark. “I thought you said you were an artist,” the man bitterly remarks, having just matched the artist to his art — presumably a comics illustration.

This moment is somewhat peripheral to the main storyline, included as a demonstration of the then 30-something-year-old’s long-delayed willingness to put himself out there on the dating scene. But in a way, it captures a concern even more essential to the book. This long, gorgeous, often rambunctious memoir is the story of a man’s search for a way out of the expectations that have kept him constrained for most of his life. Vellekoop will not remain unscathed by other people’s judgment and censure. In the end, though, this impressive book is the proclamation of an artist, in this case a cartoonist, finally staking out his claim.

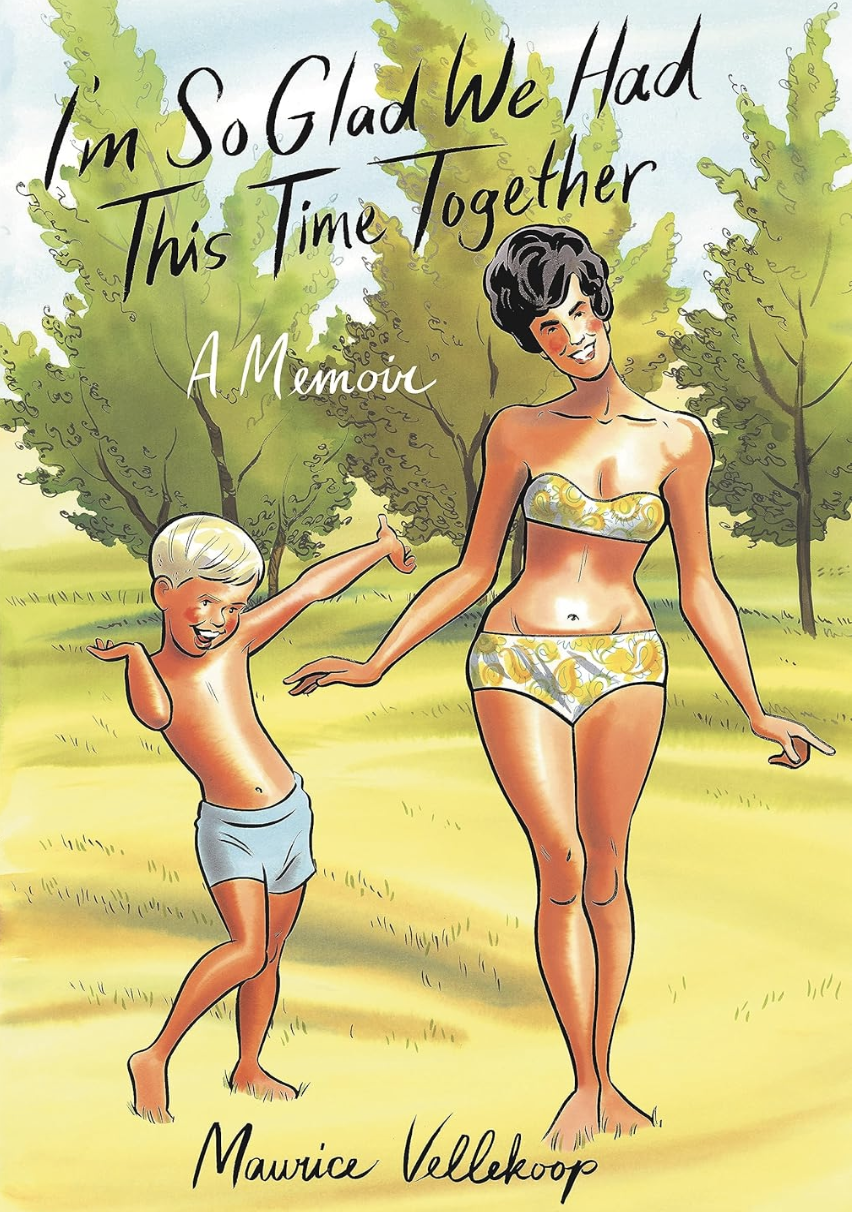

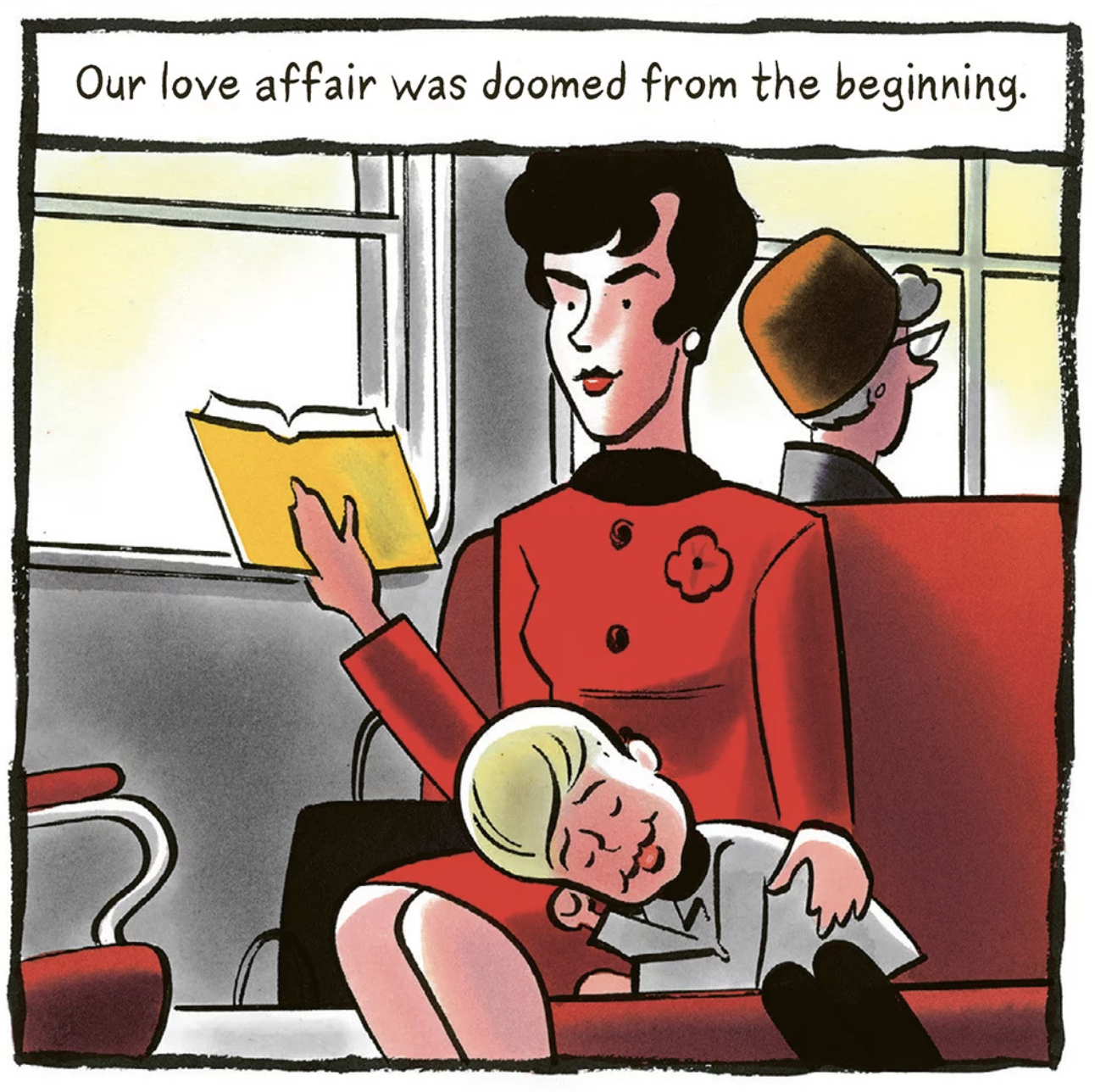

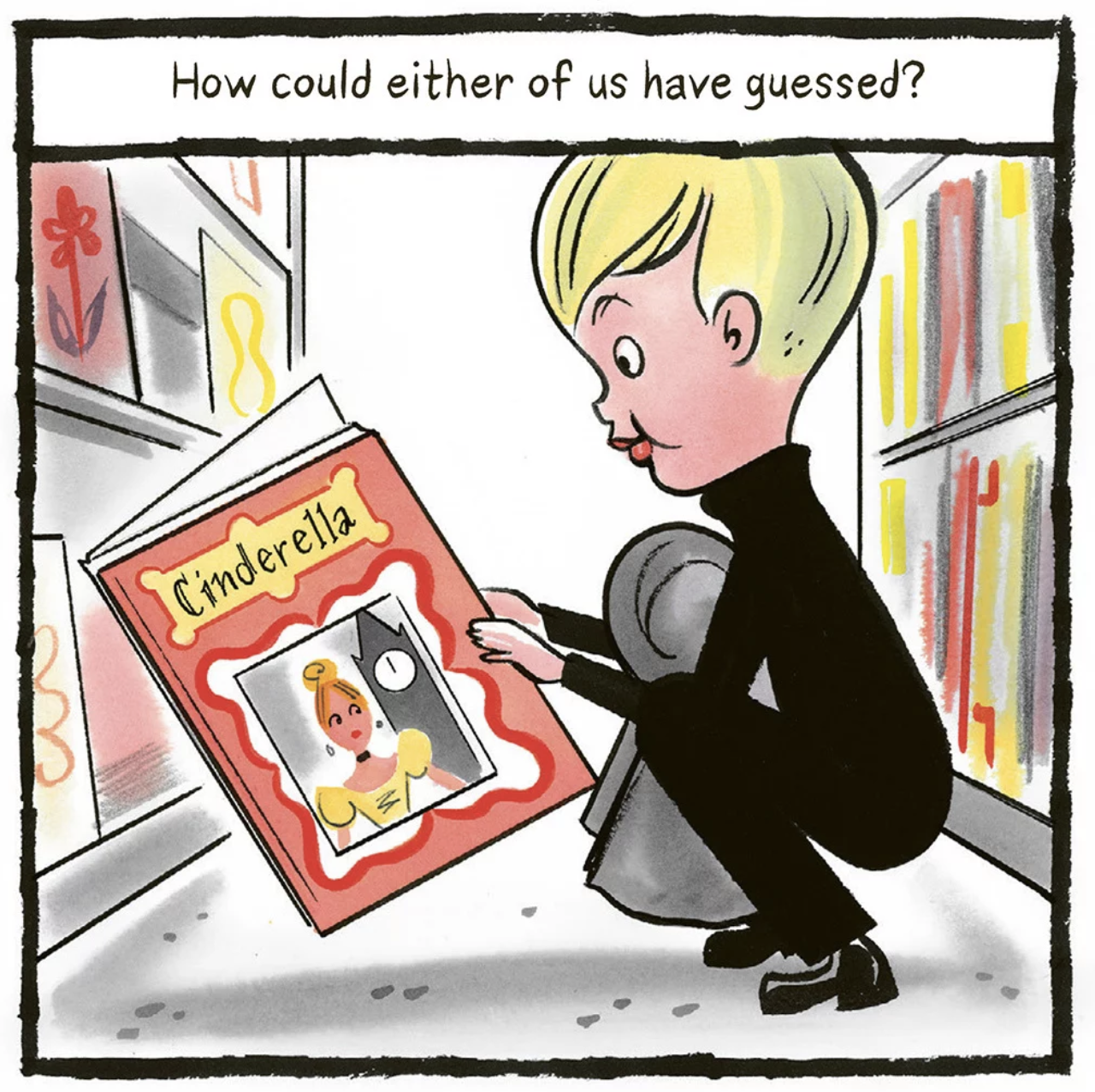

Divided into four sections tracking various throughlines from his life so far, Vellekoop opens his lavishly colored book of comics with scenes from early childhood. Born in 1964, young Maurice was the fourth and final sibling raised in the suburbs of Toronto by Dutch immigrant parents who were also avid members of the Christian Reformed Church. From his loving but complicated Mum and Dad, he developed an immediate, and passionate, connection with music and art. This working-class immigrant family displayed a Rembrandt in their living room. His mother made clothes for the entire family, also running a hair salon out of their basement. His father, an art and music lover, took him to see Fantasia when he was a little boy. It was initially through the two of them, and his adored older sister, Ingrid, that many of his great loves — and, eventually, prodigious talents — were launched.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))