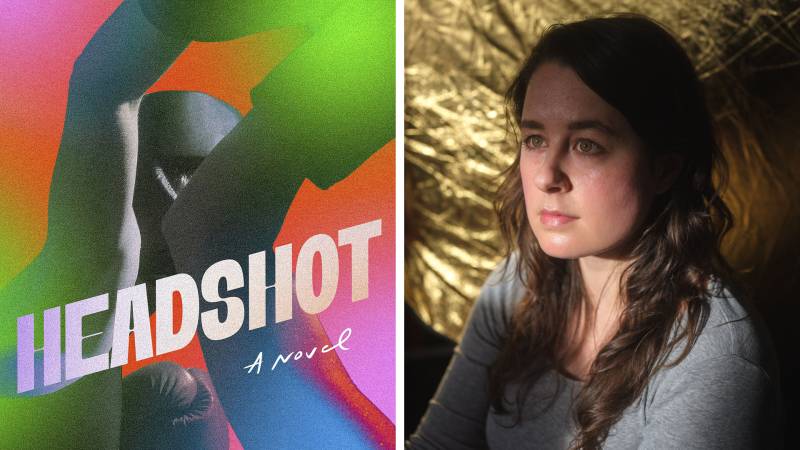

In Headshot, Rita Bullwinkel makes an electrifying claim: “Each girl born has the ability to be activated into a boxer.” Her debut novel is an absorbing study of eight teen girl boxers competing in the 12th Annual Daughters of America Cup in Reno, Nevada. It is about female potential — a small community of girls who harvest it in themselves and learn to communicate in a secret language of fists.

Though she doesn’t have a boxing background herself, Bullwinkel — an English professor at University of San Francisco— has always wanted to write a book about teen girl boxers because of how “inherently theatrical” she finds the sport. “The ring looks like a stage; the lighting looks like a stage; and it is one human in conversation with one another,” she explains.