“Being a Mexican American is tough … we gotta prove to the Mexicans how Mexican we are, and we gotta prove to the Americans how American we are. We gotta be more Mexican than the Mexicans and more American than the Americans. It’s exhausting.”

So goes the ancient proverb shared in the Jennifer Lopez-starring, Chicanx cult classic film, Selena. In the scene, Selena (a young Lopez) listens as her dad (Edward James Olmos) explains how the border-schism proximity between the U.S. and Mexico make it nearly impossible for Mexican Americans — also known as Xicanx people — to feel fully grounded in either country. Exhausting, certainly. But also beautifully fractured.

From this glaring fault line, Xicanx people are born, and it’s where we breathe ourselves into our colorful, imaginative existences. Ever seen the murals in San Francisco’s Mission District, wandered past public art in East Los Angeles, or spent an afternoon in San Diego’s Chicano Park? Where else do you regularly experience that kind of public, communal catharsis through visual art?

Rife with political and social resilience, gender fluid expressions and an ancestral sense of homeland, Calli: The Art of Xicanx Peoples — an ambitious, 53-artist exhibit opening June 14 at the Oakland Museum of California — invites audiences to embrace and navigate these multi-dimensional complexities of Xicanx communities up close.

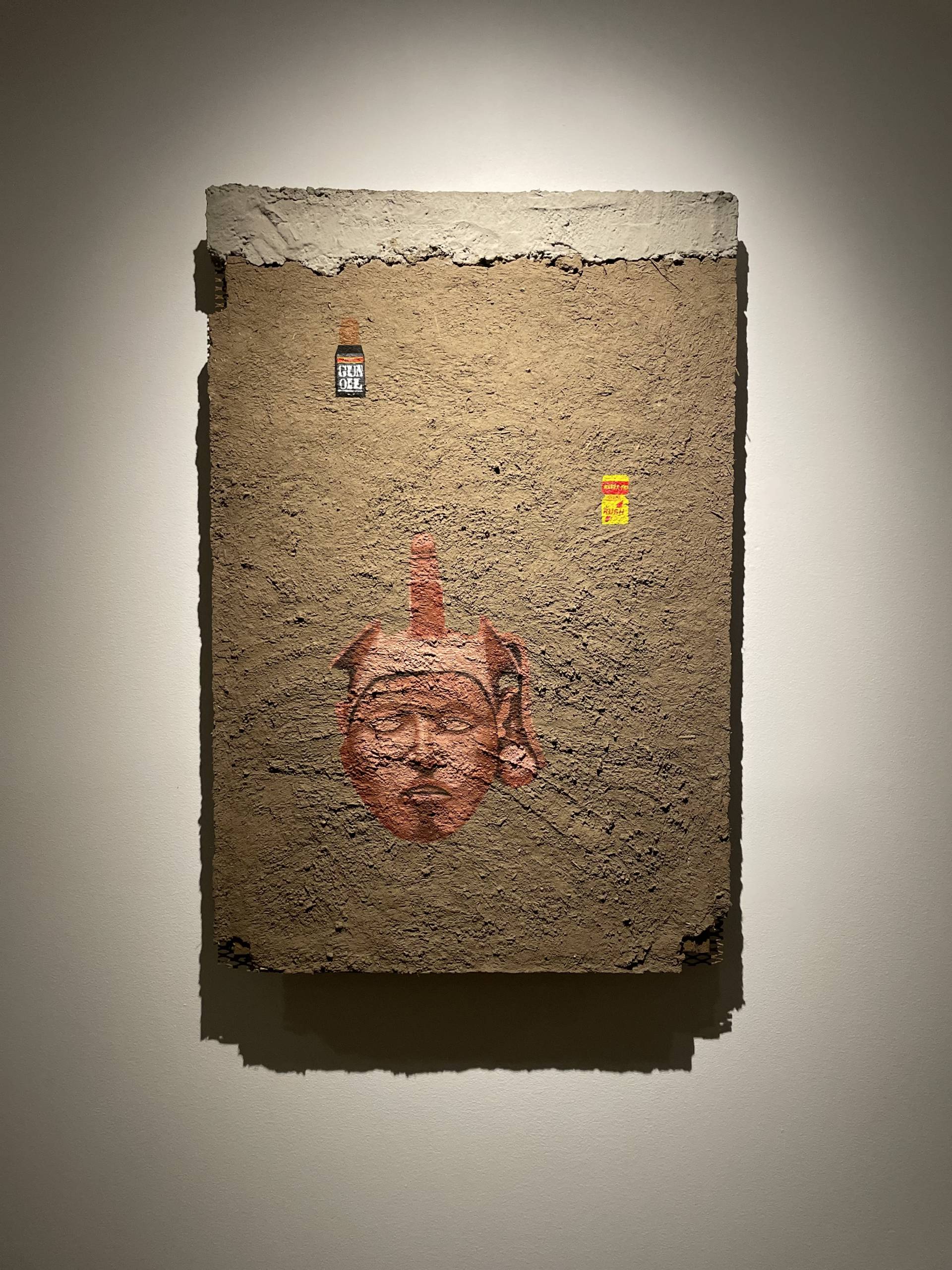

Held in the museum’s spacious, multi-room Great Hall, Calli — a Nahuatl word for home, family and lineage — opens with an adobe installation from Los Angeles artist rafa esparza (most recently featured in SFMOMA’s Sitting on Chrome). The piece serves as a portal for museum-goers, signaling a transformation of space, time and psychology as they enter the main showrooms. Titled Dispatches de Abajo, it features hand-formed, Indigenous-styled adobe sculptures and an adobe floor.

And yet, references to the brutalism of our contemporary world are sprinkled on top of earth’s peaceful sediment: a series of adobe pit bulls wearing chain collars stare menacingly beneath images of Mesoamerican figures; an acrylic can of gun oil lube painted in the corner of an adobe block. esparaza’s immigrant father was a brick maker in Durango, Mexico who taught esparza and his siblings how to work with materials like adobe. It’s something that has gifted esparza a connection to the earth in an otherwise sharply concrete L.A. landscape.

Like esparza, many Xicanx artists have had to build their own mythologies, create their own paths and shape their own futures by calling up an ancestral past in a land that is neither here nor there. (Audio recordings of six year’s worth of California’s tectonic movements play softly from speakers as visitors walk through esparza’s womb-like installation.)

That search for an ethereal belonging is a central theme throughout Calli. The exhibit is a healthy mix of contemporary works (kinetic papel picado, a mobile curandera station, a makeshift elote cart) and historical documents (archival posters, canonical prints, newspaper clippings, poems) that function as both an introduction to Xicanx history and an impressive Xicanx Hall of Fame for the already-initiated.

The trove of historical material is largely thanks to the late Chicana queer activist and professor Margaret “Margie” Terrazas Santos, whose efforts to collect posters from the Third World Liberation Front and Chicano Rights Movement culminated in an expansive and iconic resource for the OMCA, who acquired her visual library from living family members.

An intergenerational array of artists — including esparza, Consuelo Jimenez Underwood, Carlos Francisco Jackson and a legion of others — were invited to create works in response to the posters, depicting Xicanx lore as not just something of the past, but of the current moment and beyond.

Jimenez Underwood confronts borders, military violence, displacement, migration and territorial conflict with a massive, site-specific contribution that spans the entirety of the exhibit’s largest wall with a multimedia mural. Jackson revisits the violence of the National Chicano Moratorium in 1970 with a silkscreen print.

Nearby, an original prose excerpt from Luis Valdez — a pivotal Xicanx playwright who founded Teatro Campesino in 1965 during the rise of United Farm Workers — is displayed within a case. His words outline the dualities of Xicanismo: “sentimental and cynical, fierce and docile, faithful and treacherous, individualistic and herd-following, in love with life and obsessed with death.” Calli is all of this, at once, in a swirl of mediums, fabrics, textures and generational perspectives.

One of the expansive show’s highlights is its emphasis on queer and feminist Xicanx perspectives. Through photography, digital prints and various installations (video, audio and otherwise) viewers are presented with an alternative lens through which to understand the Xicanx pursuit of place and comfort within the largely patriarchal culture of Mexican machismo.

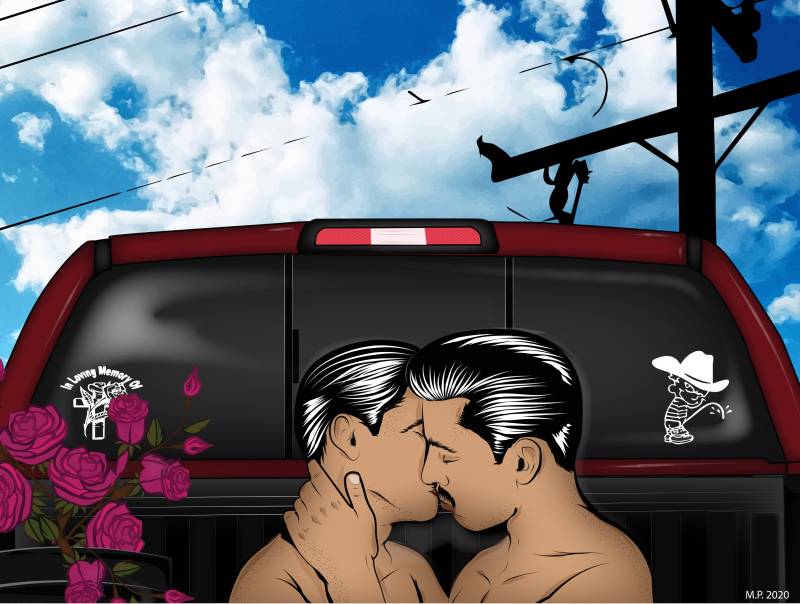

The “autodenominación” (or act of self-naming) is an intuitive, if not necessary survivalism, that many Xicanx folks have had to perfect in dealing with not only racism, but homophobia. In a stunning subversion of machismo, a large Manuel Paul print shows two Xicanx men wrapped around one another behind a pickup truck, lips touching lips, with the well-known iconography of Mexican masculinity surrounding them (such as a bootleg Calvin and Hobbes sticker in which Calvin is wearing a cowboy hat and taking a piss — a classic Mexican pick-up truck adornment).

Like the very Xicanx people the galleries are attempting to present, however, it is impossible to express each singular experience in all of its fullness. Rather than dig deep into one particular iteration of Xicanismo, Calli opts to widen the spectrum, and thus, visitors are more likely to miss a particular angle or texture on display.