The show has a straightforward but interestingly complicated premise: artworks are living, breathing, decaying, broken things. All artworks, like all things, are transitory. Organized by the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive’s chief curator, Margot Norton, To Exalt the Ephemeral: The (Im)permanent Collection might be a conservator’s nightmare, but it’s also an audience’s dream.

This is Norton’s first curatorial project since joining the museum last year, and it’s based on an idea she dreamed up while interviewing for the job. Pulled from the museum’s collections, the show focuses on ephemeral, conceptual and performance art — genres with a rich history in the Bay Area. Yet today, we see less of the ephemeral and more that is easily transacted upon.

Should art function like Dorian Gray, remaining perfectly young as time passes? It’s definitely easier to assign value to such work, and then let it sit, unblemished, accruing monetary worth on the art market.

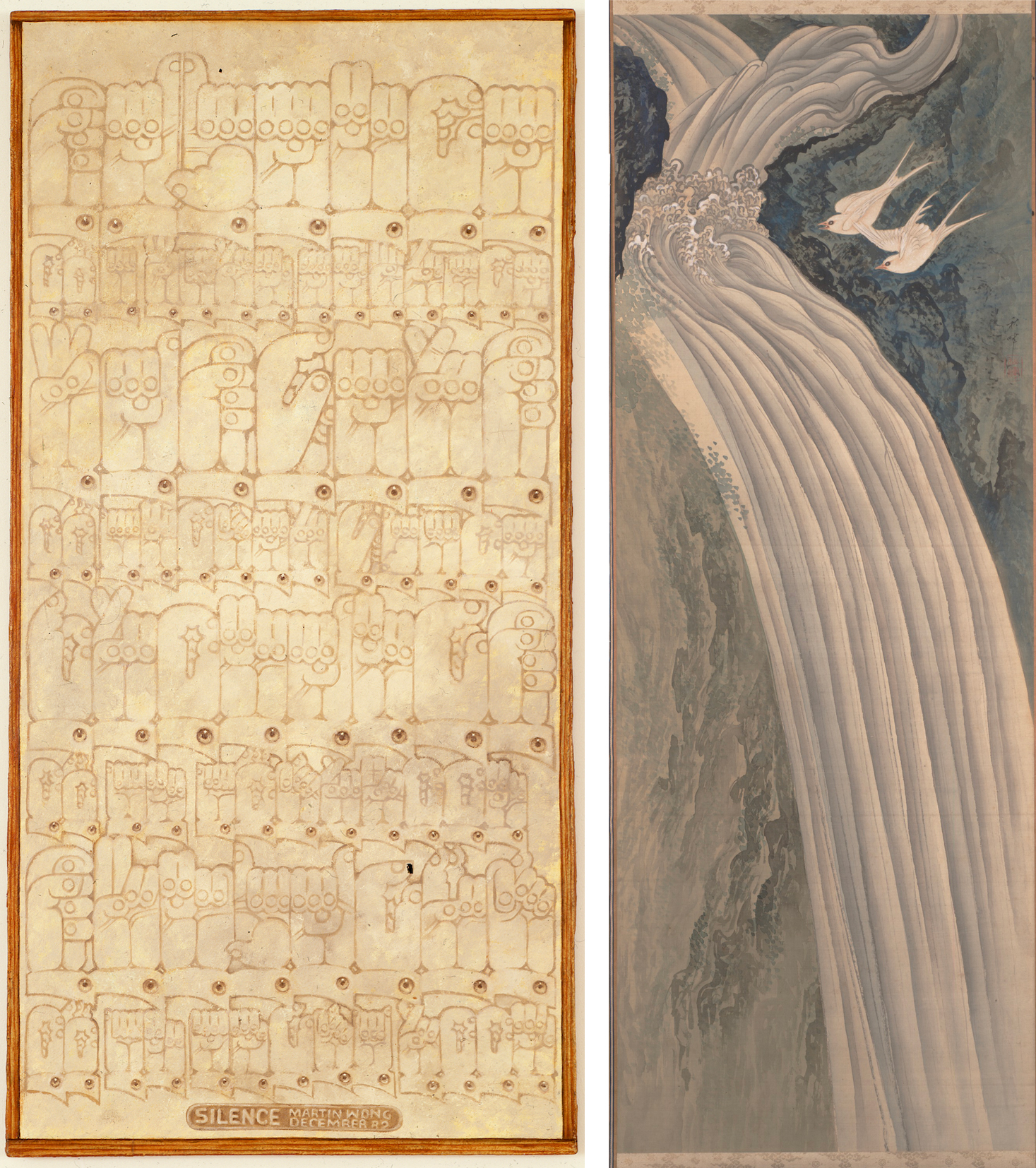

To Exalt the Ephemeral honors an alternate route. Included in the exhibition are examples of artists who rebelled against the idea of permanence, either because they refused to participate in the status quo of the art market or because their artistic concerns took them into novel territory. The tension here is that the majority of the works in this show reference the idea of ephemerality as a subject rather than evidencing it physically. For example, a suite of Andy Warhol Polaroids refers to the fleeting nature of time as captured in a snapshot — but there is little in the medium that challenges traditional modes of photography.

The show opens with works that are the most materially relevant to the theme of ephemerality: objects that embody a sense of transience, because they were constructed with organic materials or because they are traces of past actions and fleeting moments.