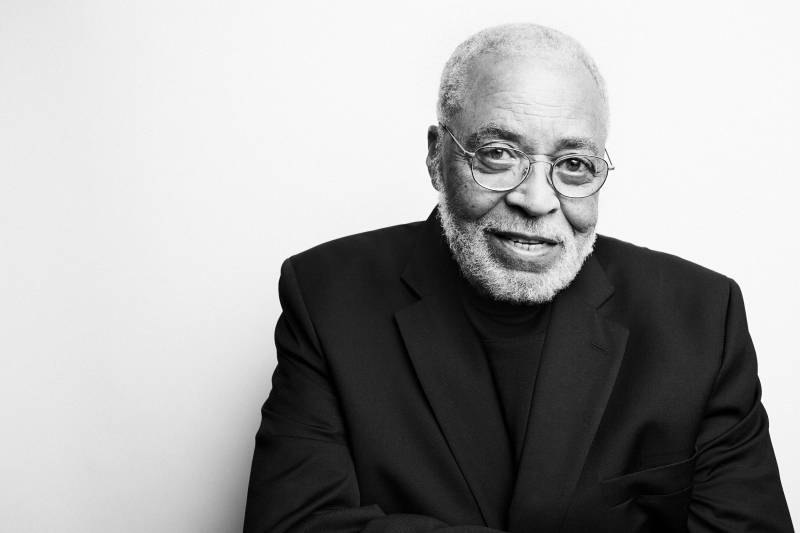

One of America’s most beloved actors, James Earl Jones, died Monday at age 93. He was at home in Dutchess County, N.Y. surrounded by his family, his longtime agent Barry McPherson confirmed to NPR.

In addition to an illustrious stage career — which included roles in classics like Macbeth, Othello and The Iceman Cometh — Jones also had an extensive film career, appearing in Dr. Strangelove, Field of Dreams, and The Hunt for Red October. He voiced Mufasa in The Lion King, and as Darth Vader, he delivered the line that still sends shivers up the spines of Star Wars fans: “I am your father.”

James Earl Jones was born on Jan. 17, 1931, in Arkabutla, Miss. He was raised by his grandparents. When he was 5 years old, the family moved to a rural farm in Dublin, Mich. Jones said the move so traumatized him that he developed a severe stutter that continued until he was in high school.

“I was able to function as a farm kid, doing all those chores where you call animals,” he told WHYY’s Fresh Air in 1993, “and I certainly let the family know what my needs were. But when strangers came to the house, the mute happened. I didn’t want to confront them and I wasn’t ready. I hid in a state of muteness.”

Then a high school teacher found a way to help: “He one day discovered that I wrote poetry and he said to me, ‘This poem is so good I can’t believe you wrote it. The way you can prove it to me is to get up in front of the class and recite it by heart.’ And I accepted the challenge and did it, and we both realized we had a means — we had a way of regaining the power of speech through poetry.”