There are two love stories at the center of new documentary, Super/Man: The Christopher Reeve Story. One is the relationship Reeve shared with his devoted wife, Dana. The other is the lifelong friendship the Superman icon shared with his college roommate, Robin Williams. If Reeve was alive today, Glenn Close asserts at one point, Williams would be as well.

“I believe that,” she emphasizes. And you believe her.

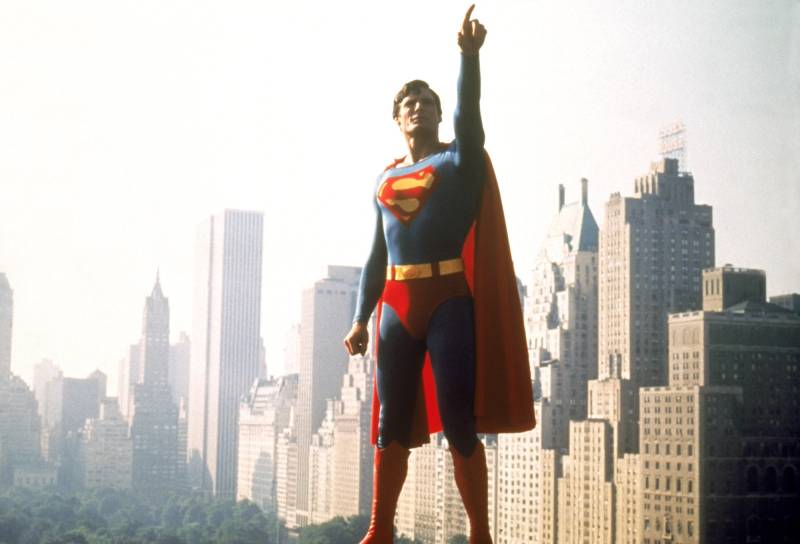

Indeed, there is a gut-wrenching amount of tragedy in Super/Man — the kind of series of cruel and unusual events that borders on the unfathomable. We are introduced to Reeve as a serious, Juilliard-trained actor who made his fortune embodying DC Comics’ most famous superhero, but whose greatest passions revolved around the great outdoors. One day in 1995, aged 42, Reeve took an awkward tumble from his horse and somehow suffered a spinal injury so severe, there is talk in the film of the ways in which his head needed to be “reattached” to his body.