While Peter sees Naomi mainly in her grungy, noisy, illegal shared flat, he and Sylvia meet regularly for civilized meals and arm-in-arm strolls through familiar streets in the rain. (It’s always raining in this novel.) They talk easily about her lectures and a big discrimination case he has won against a business with a demeaning dress code for its female employees. Rooney conveys the enormous comfort Peter finds in Sylvia so well that we share “the deep replenishing reservoir of her presence.”

Ivan is as socially awkward and reticent as his brother is dominant and ambitious. Despite a degree in theoretical physics, he barely supports himself, taking on just enough freelance data analysis work to enable him to focus on competitive chess. After a weekend chess exhibition where he plays 10 people at once at a local arts council several hours outside Dublin, the program director gives him a lift to his rented lodging for the night. Margaret, 14 years Ivan’s senior, is guiltily separated from her alcoholic husband. The tentative but intense connection that unfolds between these two sidelined people is one of the great pleasures of this novel.

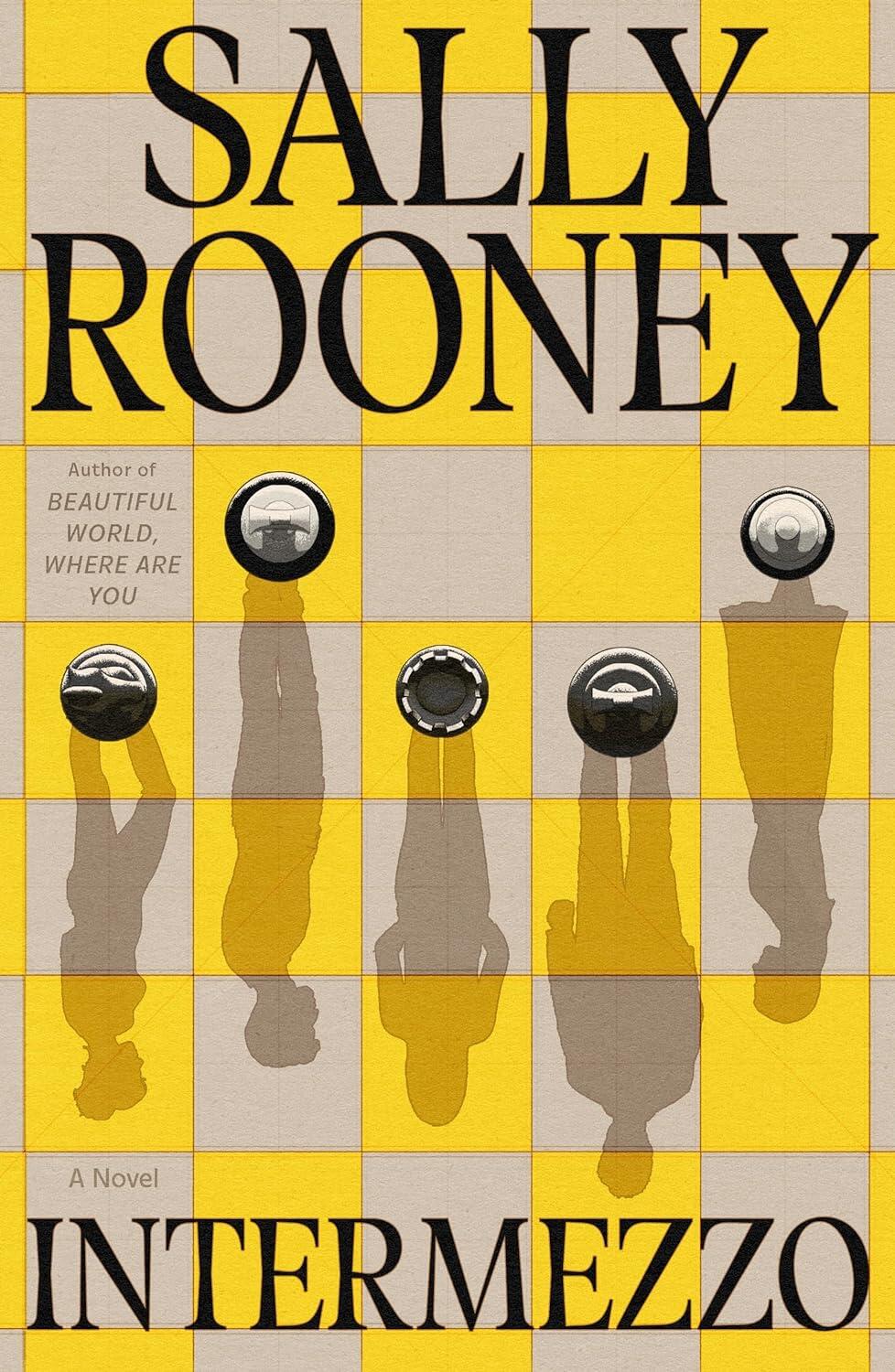

When the brothers get together for dinner at Sylvia’s urging, Ivan cautiously opens up about his new relationship. Peter’s kneejerk reaction is disparaging, which causes Ivan to hit back: “I’ve hated you my entire life.” With its fraught fraternal dynamic, Intermezzo taps into a classic literary theme — think Cain and Abel, Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, Elizabeth Strout’s The Burgess Boys, Sam Shepard’s True West, and even James Herriot’s All Creatures Great and Small.

The novel is also sprinkled with fragmented quotes from various literary classics, including Hamlet, The Waste Land, The Golden Bowl, and Ulysses — which Rooney duly cites in her endnotes. But don’t let the erudition put you off. Embedding quotes from beloved texts has become popular with writers, at once a way of paying homage and adding layers of meaning.