It’s difficult to suppress a dazed smile as the elevators open on the seventh floor of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. The sensory bombardment is immediate: speakers play the sounds of a cheering crowd; split-flap displays clatter above; a giant image of 1985 Bay to Breakers runners surrounds an arched entryway; and white stripes peel off in different directions across the gallery’s wood floor.

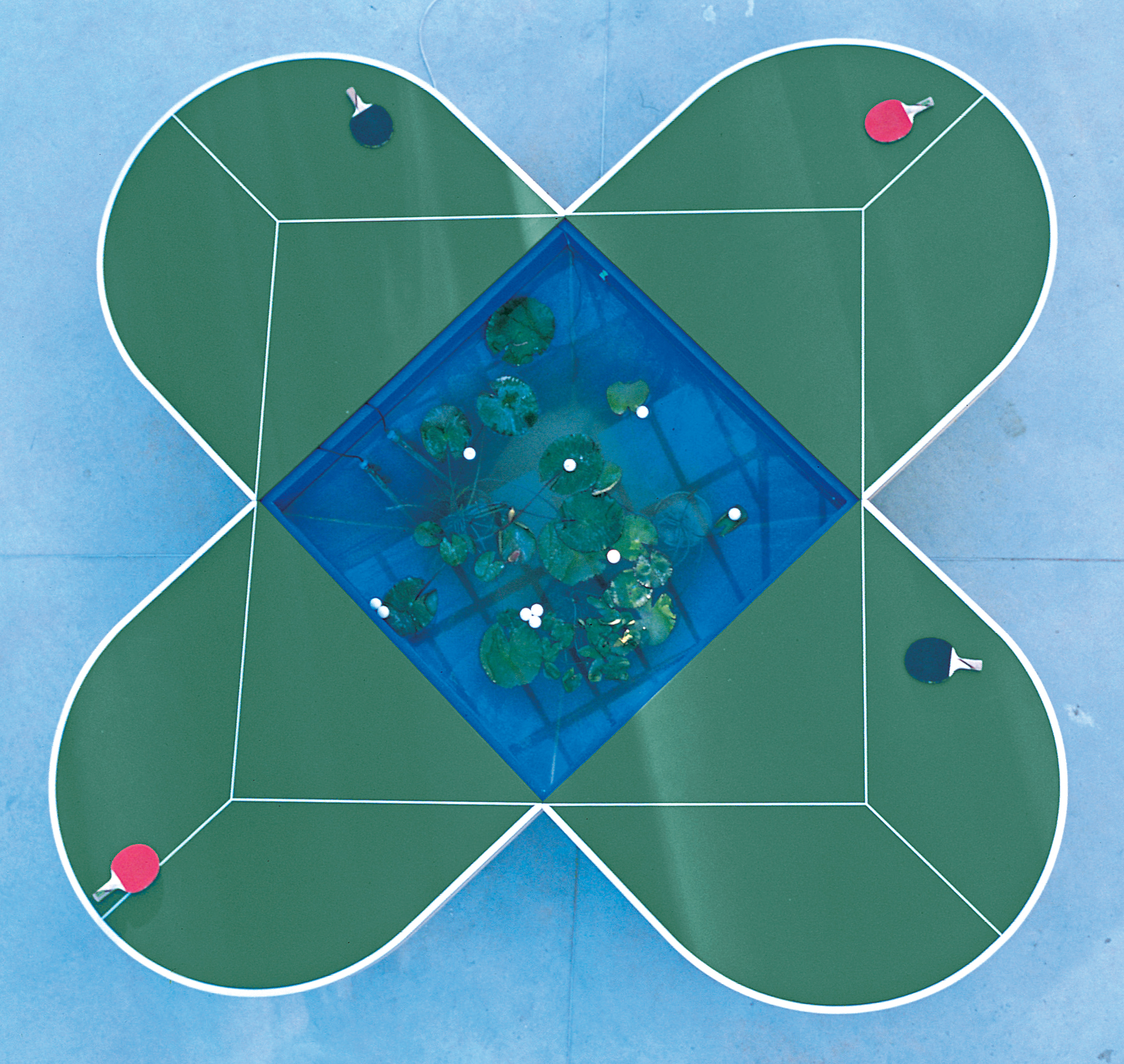

The effect is multipurpose gym, funhouse, cacophony. In other words: museum show as stadium experience. Get in the Game, SFMOMA’s largest-ever exhibition, contains over 200 artworks and design objects spread across the length of a football field. Paintings and photographs hang beside surfboards and tennis rackets. Notable sports moments loop jumbotron-style on overhead screens. Visitors can even play select artworks, like Gabriel Orozco’s elegant but very difficult four-sided “ping pond table” or noted prankster Maurizio Cattelan’s ultralong foosball setup.

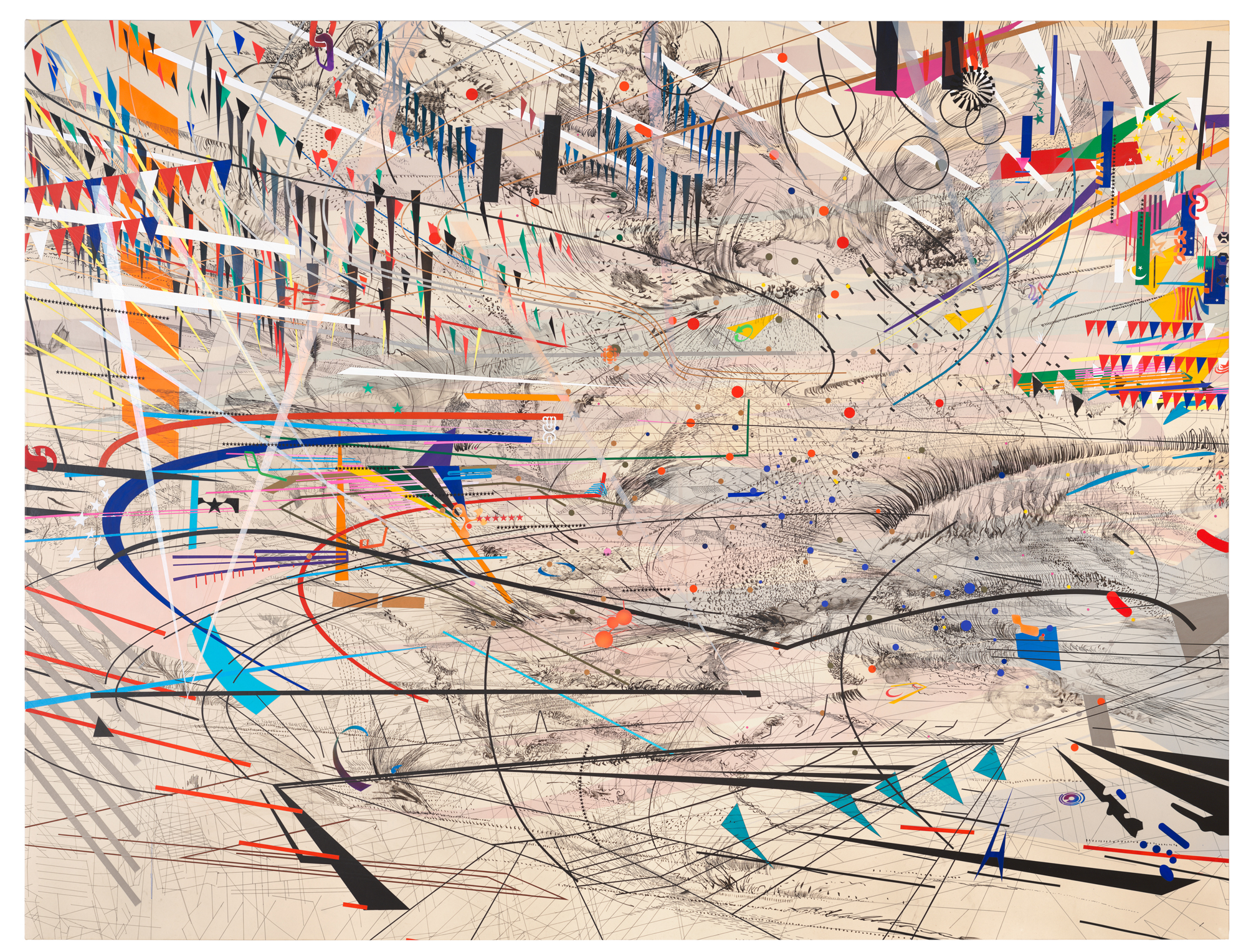

Organized thematically into five zones that address fandom, inherent drama, boundary-breaking, less organized sports and “the dark side,” the show revels in bold accent colors and curves, courtesy of exhibition design by fuseproject and One Hat One Hand. Even the intro text invites a kind of free-for-all viewing experience, giving visitors permission to zigzag around, “searching out your favorite sport or the artworks that most interest you.”

There’s plenty of beautiful work in the show, along with truly interesting displays of how athletic gear has evolved over time. But Get in the Game may be difficult for those used to a quiet, contemplative art experience. This is not an art show so much as it is a sports show with art in it. It feels like the kind of blockbuster exhibition Yerba Buena Center for the Arts might have put on in its early years, or that the Oakland Museum of California Art might stage today.

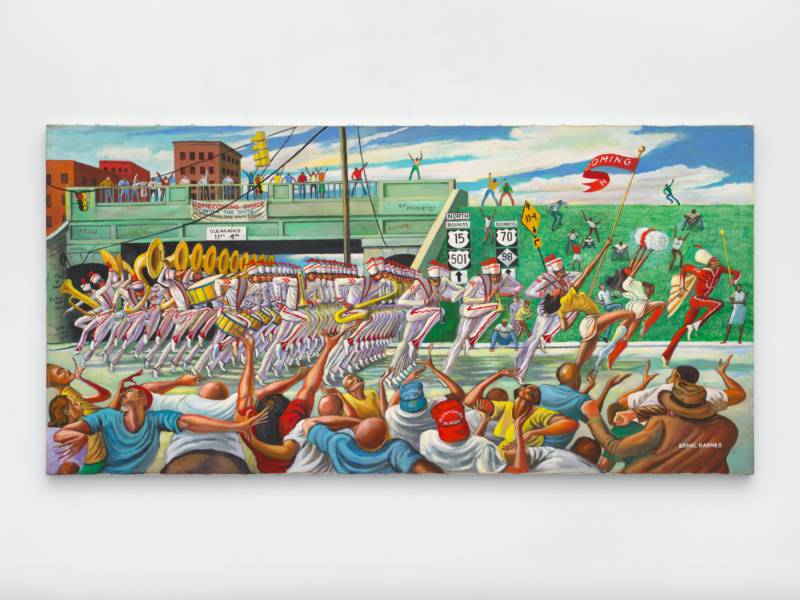

Which is not to say it’s not a rewarding visiting experience. Get in the Game contains, even for the sports-averse, something for everyone. My personal highlights — Emma Amos’ dynamic textile Hurdlers I, David Hammons’ exquisite Basketball Chandelier, Douglas Gordon and Philippe Parreno’s 90-minute Zidane video or any of Ernie Barnes’ exquisite paintings of bodies in motion — will not be everyone’s favorites. Another visitor might be equally thrilled to see Nikes or what I can only assume are rare trading cards of Joe Montana and LeBron James.