In the month since I first visited the 2024 SECA Art Award exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, much has changed. Not to the show itself: The delicate paintings by Rupy C. Tut, Rose D’Amato’s signage-inspired work and Angela Hennessy’s elegant, elegiac sculptures all remain as they did on opening night. But the world around them has shifted. My eyes, especially, are seeing things differently.

I think this is a good thing.

Art is made in a particular time and place, drawing from an artist’s unique experiences, interests and aesthetic sensibilities. But it also needs to exist beyond its maker; once a piece of art has left the studio and entered the public realm, it becomes something else (a different else) to each person who views it.

As of Jan. 7, I can’t help but see Hennessy, D’Amato and Tut’s work in relation to the devastation of the Los Angeles fires. How do we describe a place that no longer exists? How do we voice our grief? How do we imagine what happens next?

The first gallery, painted a deep navy blue, is filled with Tut’s paintings on linen and hemp paper. Her process is meticulous. Tut creates her paint with a mortar and pestle, grinding vivid pigments into powder and mixing them with gum arabic and patiently gathered rainwater.

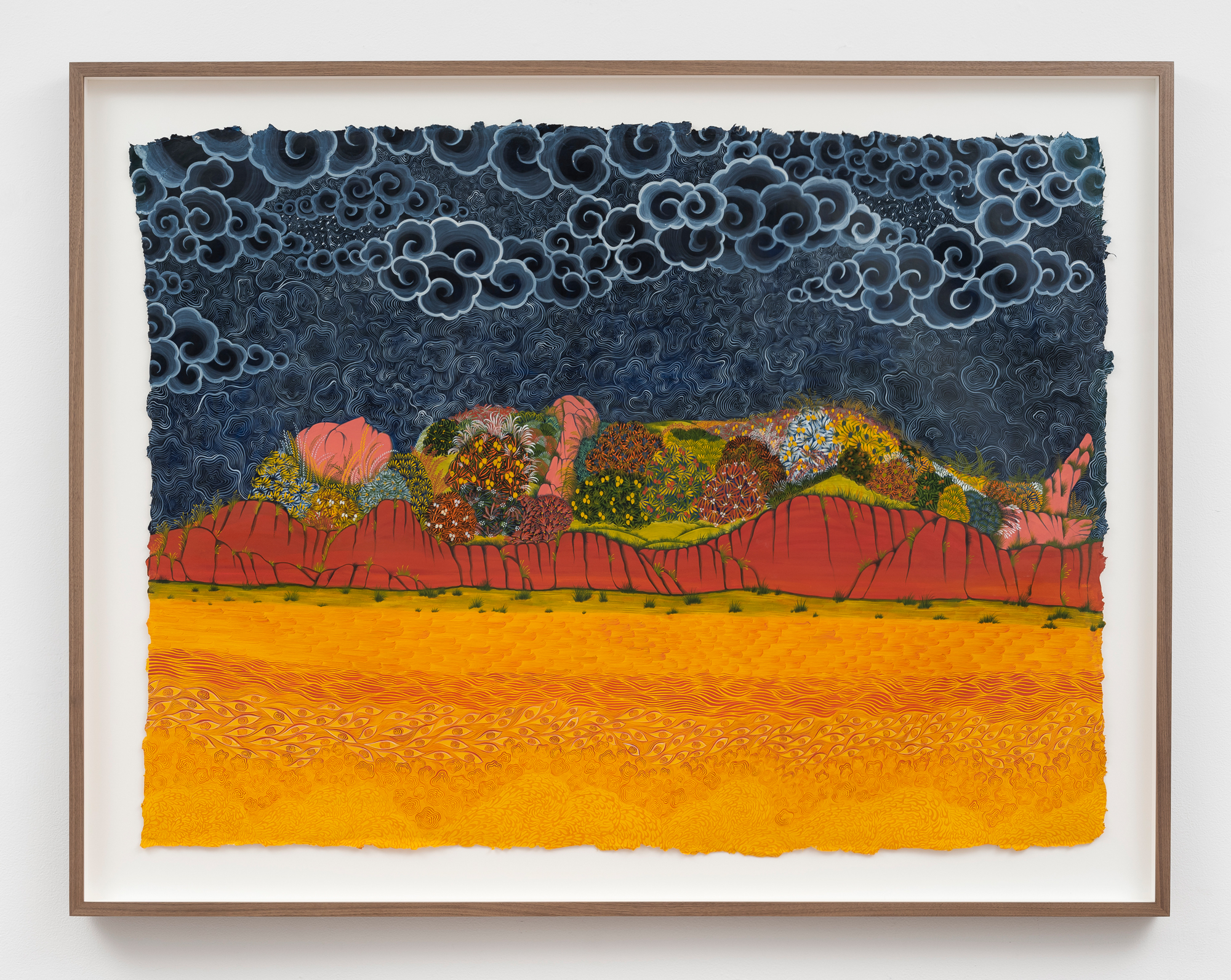

But that’s behind the scenes. What’s visible to SFMOMA visitors are the thousands of tiny brushstrokes on her surfaces. In The Dreamweaver ਸੁਫ਼ਨੇਕਾਰ (sufnekaar), a figure lies atop a mountain range, its peacefully reclining body made up of bushes, grasses and flowers in every shade of yellow and green. Above, a cloudy sky is rendered in concentric white lines on that same deep navy. In Tut’s world, every whole is made of many, many, disparate parts.