When playwright Keiko Green was in her early teens, she learned that her grandfather — her ojiichan — had worked as a food scientist for Ajinomoto, the Tokyo-based company best known for inventing monosodium glutamate, a.k.a. MSG. In that moment, Green recalls, she didn’t feel a sense of pride in her family’s contribution to culinary history. Instead, she felt something more akin to shame. For a biracial Japanese American kid growing up in a predominantly white suburb of Atlanta, Georgia, the MSG link was just one more thing that made her different.

“It just felt like I was sticking out so much,” she recalls. “And there was that teenage part of you that wants to just disappear into the background and be a little invisible.”

And anyway, wasn’t MSG bad?

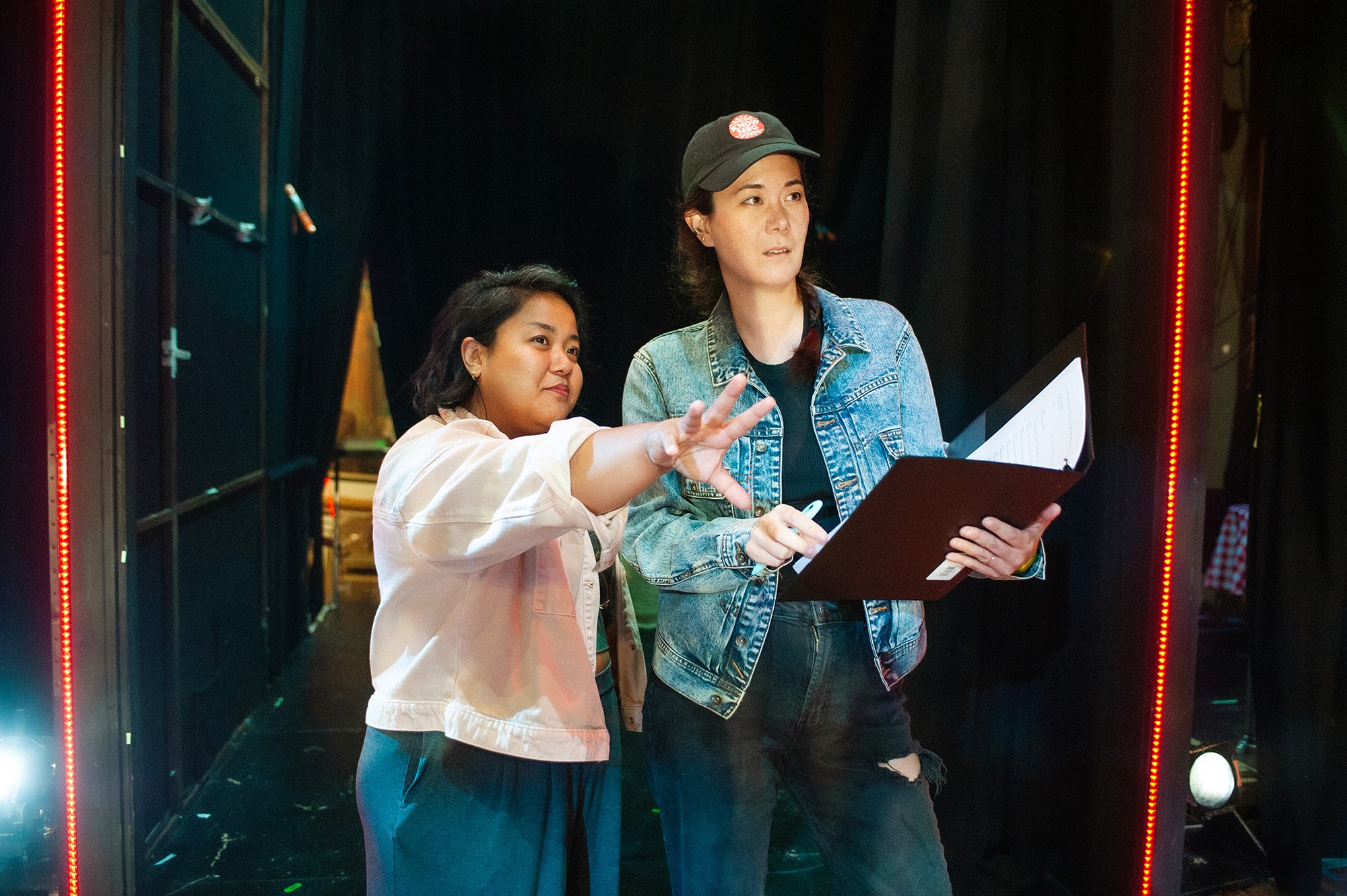

Well, no. Years later — long after Green had learned that those old “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” campaigns were based on bad science and, often, blatant racism — the playwright recreated this moment of racialized teen angst in her play Exotic Deadly: Or the MSG Play, which opens at San Francisco Playhouse on Jan. 30, directed by Jesca Prudencio.

Like Green, the protagonist, Ami (played by Ana Ming Bostwick-Singer), is an Asian American teen growing up in the late ’90s. Ami first hears about MSG from a doctor on TV who warns about the flavor enhancer “poisoning America.” When she learns that her grandfather was the Japanese scientist who invented the headache-inducing powder, it’s like finding out that her own blood is tainted. She, too, wishes she could just make herself invisible.