Even if you don’t know who Viola Frey is, chances are you’ve seen a Viola Frey. The prolific artist’s large-scale ceramics dot the Bay Area landscape and the collections of our cultural institutions. The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Oakland Museum of California, the di Rosa — all are caretakers of the late artist’s work.

Maybe you’ve flown out of the country in the past 25 years? In SFO’s international terminal, Frey’s 1999 piece World Civilization is a massive tiled grid filled with the symbology she accumulated during her five-decade-plus career: suited men, vibrantly dressed women, hands, globes and exuberant patterning.

But there’s a gap between recognizing an artist’s work and knowing why that work is an important part of local art history. A gap that can now be filled by the 228 pages of the handsome hardcover Viola Frey: Artist’s Mind/Studio/World. As a bonus, two upcoming events at California College of the Arts and pt.2 gallery, on Feb. 13 and 15, respectively provide audiences with opportunities to cement the Frey’s life and work into their timeline of rich Bay Area art lore.

Reading Viola Frey 20 years after her death, it’s difficult to believe this is the first monograph of Frey’s work. The book exists, in part, thanks Frey’s own pragmatism, evident throughout her life story in the form of savvy artwork sales, real estate acquisitions and a temporary hiatus from exhibiting. The book is published by Gregory R. Miller & Co. and Artists’ Legacy Foundation, a nonprofit established by Frey, Squeak Carnwath and Gary Knecht to steward artists’ estates after their deaths.

Three essays from Nancy Lim, Jodi Throckmorton and Jenelle Porter, along with a detailed chronology from Cynthia de Bos, the foundation’s director of collections and archives, tease out the nesting egg of the book’s title. How do interior and exterior forces shape a life’s work — and what kind of thrilling slippage can take place between the mind, studio and world?

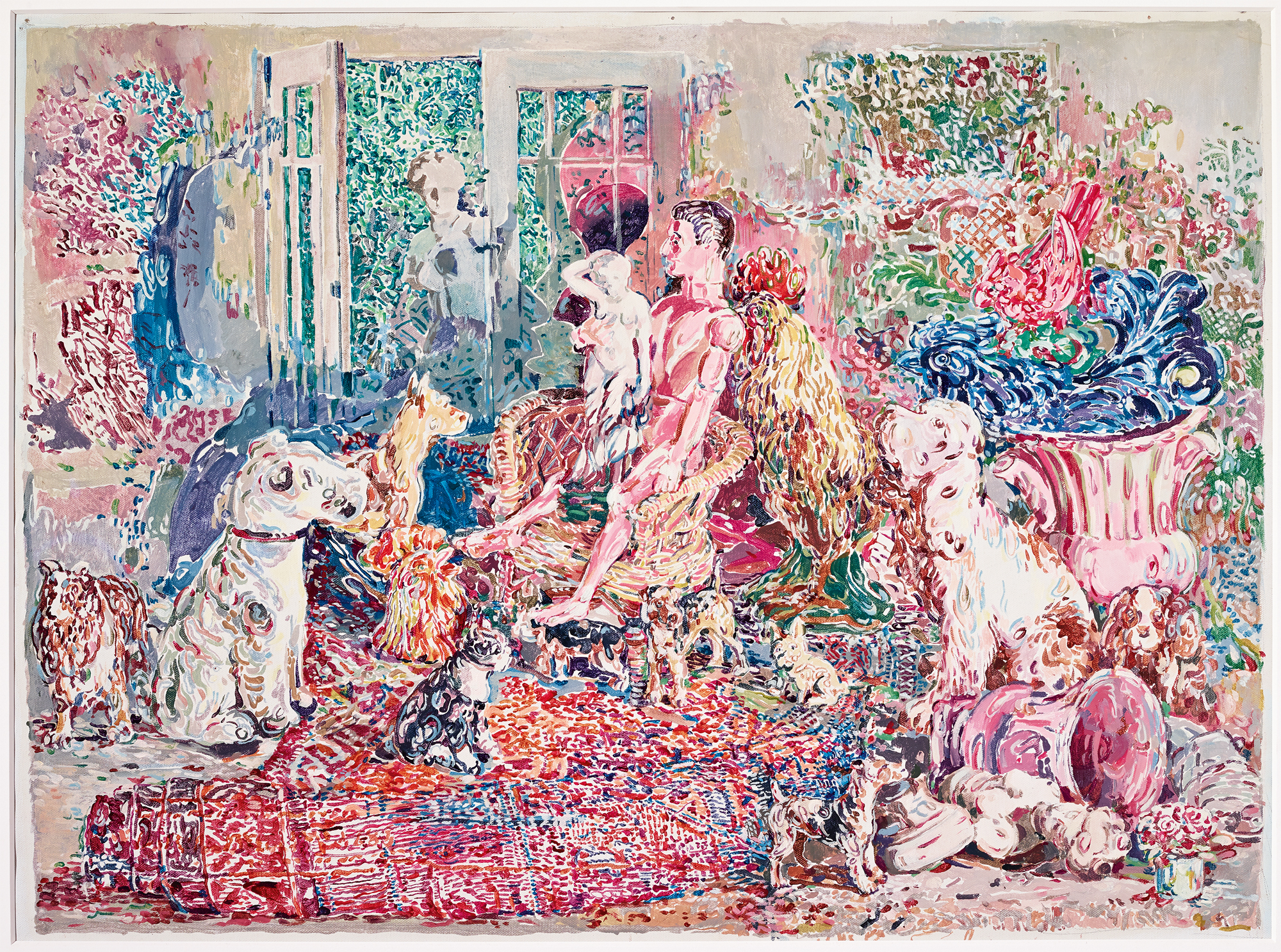

Frey grew up in Lodi on her family’s grape farm, home to scattered, defunct machinery and barns filled with her father’s collections of old stuff. (It’s a predilection Frey inherited: She was a regular at the Alameda Flea Market, which she described as a “human museum without walls,” and where she collected untold numbers of figurines.)