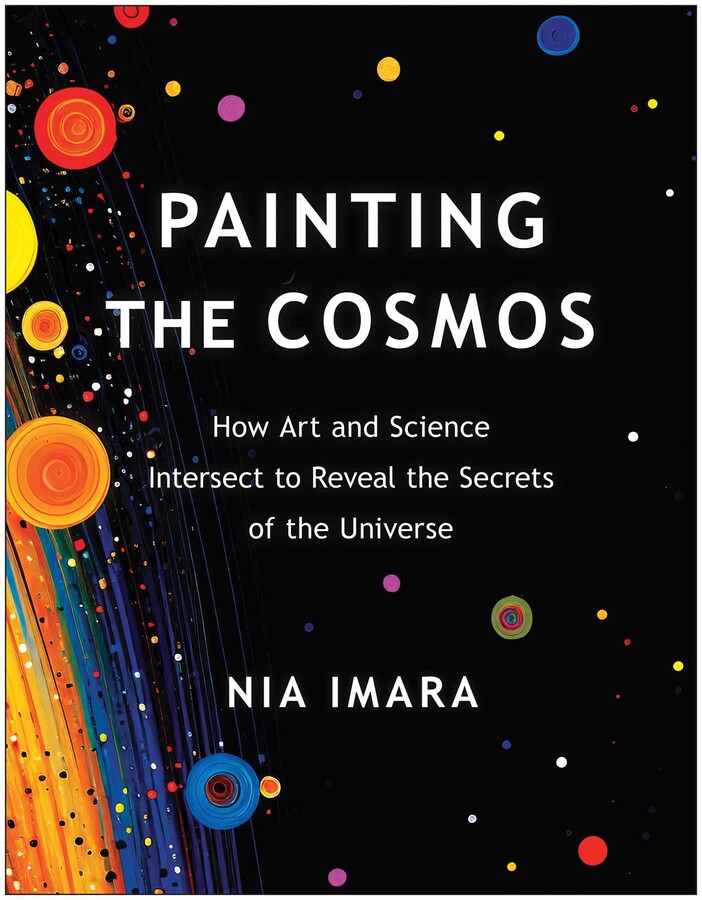

The book Painting The Cosmos challenges the notion that science and art exist in separate worlds; it also illustrates of how everything in this universe is actually connected. There is no separation, only slight differences. And from this diversity of cosmic forces, comes life itself.

The book is a science publication that reads like an uplifting conversation, packs in information like a textbook and feels like a coffee-table-worthy glossy periodical. But if you ask author Dr. Nia Imara, she’ll let you know: the book is art.

The 240-page read, published by BenBella Books and distributed by Simon & Schuster, is a window into Imara’s world, where the constant speed of light (186,000 miles per second) coexists with the fact that famed botanist George Washington Carver was also an avid painter (who made paint from peanuts).

Imara’s writing brings together stories of Chinese astronomers and Russian poets, with references to renowned painter Romare Bearden and legendary author Toni Morrison.

The book explores the rate at which the universe is expanding and delves into the study of the sun’s sound waves — helioseismology. Topics addressed include Einstein and Emory Douglas, and a reminder that we too are stardust, a perspective supported by a quote from the first African American woman to travel into space, Mae Jemison: “The really wonderful thing that happened to me when I was in space was this feeling of belonging to the entire universe.”

“That quote by Mae Jemison sums up a lot of the sentiment expressed in this book,” Imara says.

From Physics to astronomy to art

Raised in Oakland, Imara is a graduate of UC Berkeley’s Department of Astronomy and a professor at UC Santa Cruz. In her book, another quote from Mae Jemison speaks directly to the author’s personal story: “Science provides an understanding of a universal experience. Art provides a universal understanding of personal experience.”