Kevin Epps’s selective snapshot of the African-American experience at Alcatraz, The Black Rock, pushes through the fog of history in search of shards of contemporary relevance. When it finds them, the one-hour documentary comes into wrenching, pinpoint focus. Most of the time, however, the film comprises a riveting but thematically blurred collection of recollections.

Depending on your perspective, I saw The Black Rock under ideal or awful circumstances. Epps, who emerged on the scene with a bang in 2002 with Straight Outta Hunters Point, ferried a boatload of backers, friends and sponsors to Alcatraz on a dank Tuesday night two weeks ago for the premiere. After a mood-setting, ranger-led tour of the prison, we gathered in the dining room to watch the film.

Alcatraz ceased operating as a penitentiary in 1963 (after just 29 years housing the most incorrigible inmates in the federal system), but sitting in the chilly darkness I felt most of that distance evaporating. (My notes are unusable scribblings, though, a consequence of wearing gloves.) At the same time, this wasn’t the best venue for assessing the work, as only the folks in the front row had an unobstructed view of the screen.

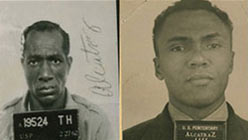

The Black Rock juxtaposes interviews with surviving inmates and guards of various races — a necessity, I suppose, given the scarcity of people around with first-hand knowledge of Alcatraz as a prison, but one that dilutes the film’s stated emphasis on black prisoners — with segments on three special cases: Harlem gangster Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson, Depression-era counterfeiter Robert Lipscomb and William “Ty” Martin, the only black member of a famous, failed 1939 escape attempt.

Johnson is a colorful character, no doubt about it, and it’s intriguing to hear that he was a moderating influence on the other prisoners during his years on the Rock. But the most compelling figure is Lipscomb, who was given 25 years in 1929 for passing a couple of hundred dollars worth of fake bills. “Prison became a university for him,” somebody recalls in The Black Rock, and Lipscomb was so learned and determined that he challenged the prison’s continued segregation policy after the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education. He got no satisfaction, only a reputation as a troublemaker who years later was sent to a mental institution.