Editor’s note: KQED Arts’ award-winning video series If Cities Could Dance is back for a third season! In each episode, meet dancers across the country representing their city’s signature moves. New episodes premiere every two weeks.

What’s long been known to Washington, D.C.’s black population is finally official: Go-go is the music of the nation’s capital.

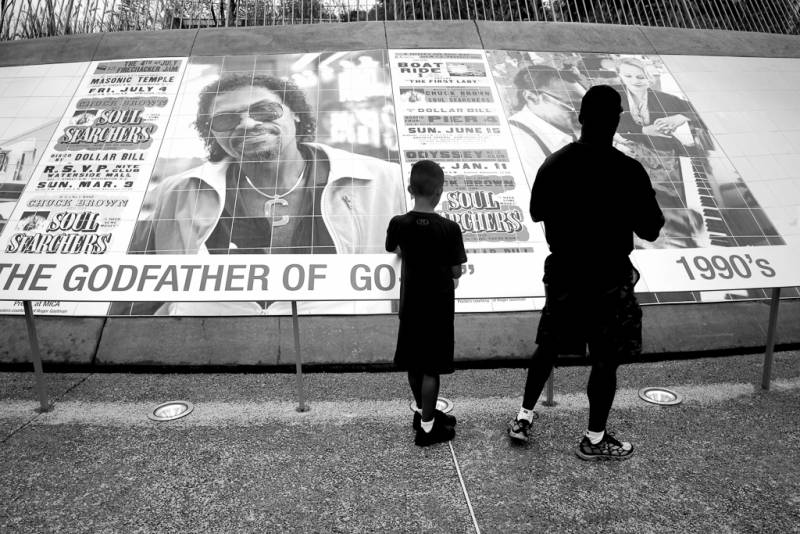

The history of go-go—a mixture of relaxed funk, gospel, jazz, call and response, and Afro-Caribbean beats—stretches back into the 1970s and starts with a musician named Chuck Brown, a fixture of the D.C. music scene. Together with his band, the Soul Searchers, he created a type of music that demands bodily movement.

Over the years, as the go-go the beat got faster and bouncier, a dance evolved alongside it. Today, the style known as Beat Ya Feet is inextricable from the music that drives it. Defined by rapid footwork, the dance was born in southeast Washington, D.C., where Marvin “Slush” Taylor created Beat Ya Feet in the late 1990s.

John “Crazy Legz” Pearson first started dancing around the same time. In his Anacostia neighborhood, Beat Ya Feet spilled out of clubs and house parties into the street, set to the music of TOB, Junkyard Band and TCB. “It was like we represented our neighborhood,” he remembers. “And it motivated me to practice, practice, practice, because I didn’t want to let my people down.”

Nothing about Beat Ya Feet is slow or tentative.

“Go-go has a lot of different rhythms within the sound,” says dancer Kevin “Noodlez” Davis, one of Legz’s protégés. “You could dance to the rhythm of the rapper or you could dance to the rhythm of the keyboard.”

Acknowledgment of go-go as the city’s official music is also an acknowledgment of D.C.’s rich cultural history as a majority-black city (which, due to demographic changes, is now no longer the case). Much of that culture is rooted in the Shaw district and Barry Farm, an area of southeast D.C. settled by freed men and women and built from the ground up, with little to no assistance from the city itself. In 1941, the government seized sections of the community’s land to build a public housing development, which in turn became a hub of activism in the decades that followed. In the ’80s, the emerging go-go scene flourished there, and it’s where Slush invented Beat Ya Feet.

(Today, only 32 Barry Farm buildings still stand, their future uncertain. The rest were demolished to make way for new development.)

With rising unaffordability and gentrification, the city’s black population has increasingly been pushed out of central D.C. and into the suburbs of Maryland and Virginia. Years of cultural displacement and erasure came to a head in April 2019, when the community rallied around an unassuming corner store in D.C.’s Shaw neighborhood. At Central Communications, go-go music played over outdoor speakers every day, as it had since 1995. But the resident of a new luxury condominium in the neighborhood complained about the noise to T-Mobile national headquarters, forcing the store owner to turn his music off. Thousands of D.C. residents filled the streets in protest; #DontMuteDC was the rallying cry.

The next generation of Beat Ya Feet dancers is well aware of the legacy they’re upholding and the history of the city they represent. Tierra “Poca” Parham runs Raw Element Dance Studio in Maryland, but she’s deeply tied to D.C.—and Beat Ya Feet moves are the embodiment of that connection. Legz started the Who Got Moves Battle League at the Boys and Girls Club of Greater Washington, training the next generation of fast-moving go-go fans.

Watch Legz, Noodlez, Poca, Delow, Soul and Litty dance across iconic D.C. locations, including the Lincoln Memorial, Anacostia’s go-go mural (Many Voices, Many Beats, One City, painted by Cory L. Stowers), at the corner of Florida Avenue and 7th Street, and in front of the Howard Theatre, at the heart of the city’s Shaw neighborhood. — Text by Sarah Hotchkiss

From Anacostia’s iconic go-go murals to the historic Howard Theatre, learn about the locations featured in this episode of If Cities Could Dance.