There are only two things wrong with Peter L. Stein's American Masters documentary Jacques Pépin: The Art of Craft, which premieres at San Francisco's Castro Theatre on Tuesday, April 25, 2017 and will premiere nationally on PBS stations Friday, May 26, at 9pm. First, it's not long enough; Pépin is such a charming character that -- especially in film digest form -- he leaves us wanting more. The film fizzes, pops and then is gone, like the delicate bubbles in a fine champagne. Second, this "American" master's French accent is still pretty thick, even after all these years. Though that is partially the point. In a political climate that puzzlingly discounts the contributions of immigrants, Pépin's adventure is a buoyant illustration of the catalytic grit, wit and innovation one newcomer can bring to an America still dreaming. Stein says, "It's sometimes really nice to remember that people come to these shores, do good in the world and build something that actually changes culture."

Needle scratch. Rewind. Whenever we revisit the lives of celebrity chefs whose revolution eventually stocked our grocery store shelves with foods we now take for granted, we must first imagine the landscape BEFORE they arrived. We have to visit the U.S. supermarket with a young Jacques Pépin to discover with horror the only mushrooms on offer come in a can. The industrial practices that fed the troops in WWII have been weaponized to feed the masses and to make "daily household drudgery" (like cooking) a thing of the past. Everything is convenient, pre-sliced and pre-packaged. This idea is repeated in several recent documentaries, but given my own proximity to Rainbow Grocery and Whole Foods market, I still find it hard to grasp.

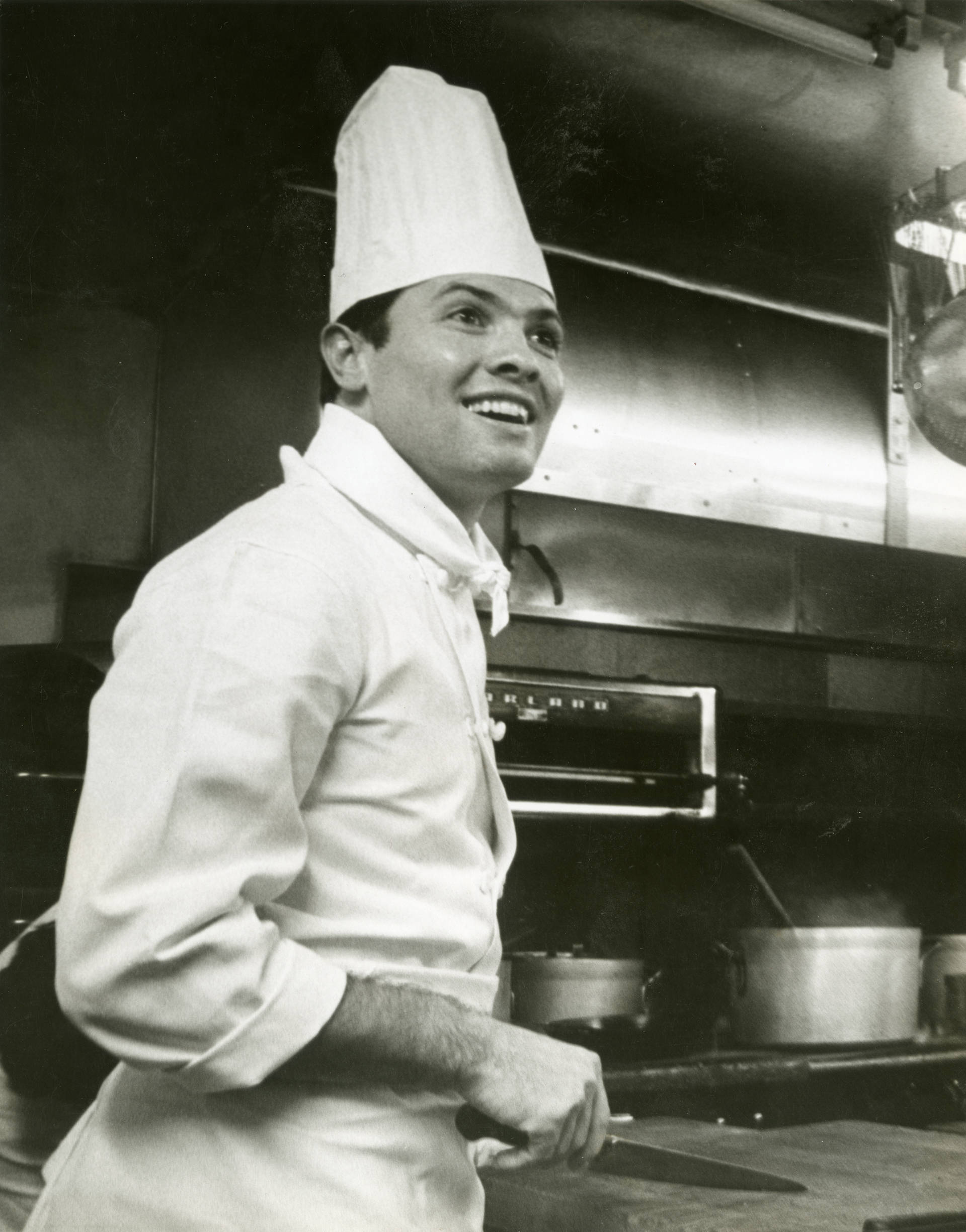

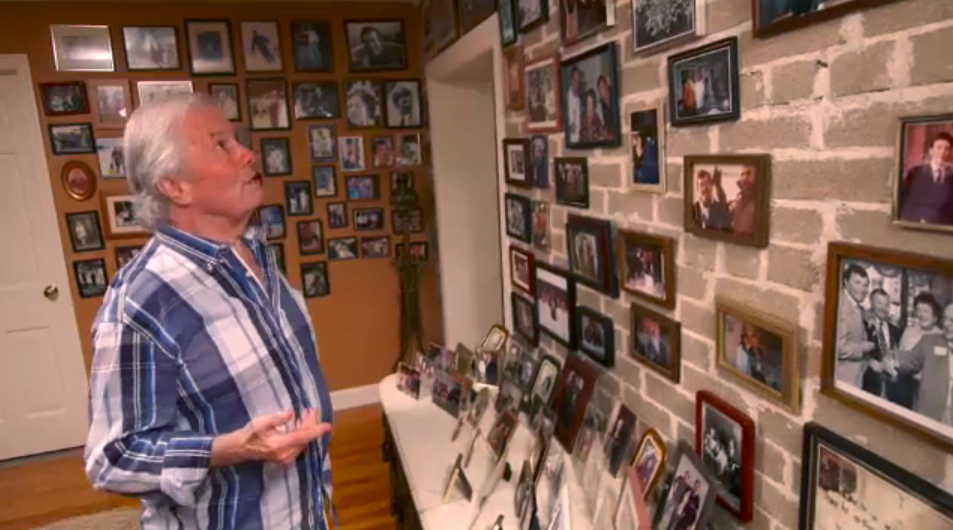

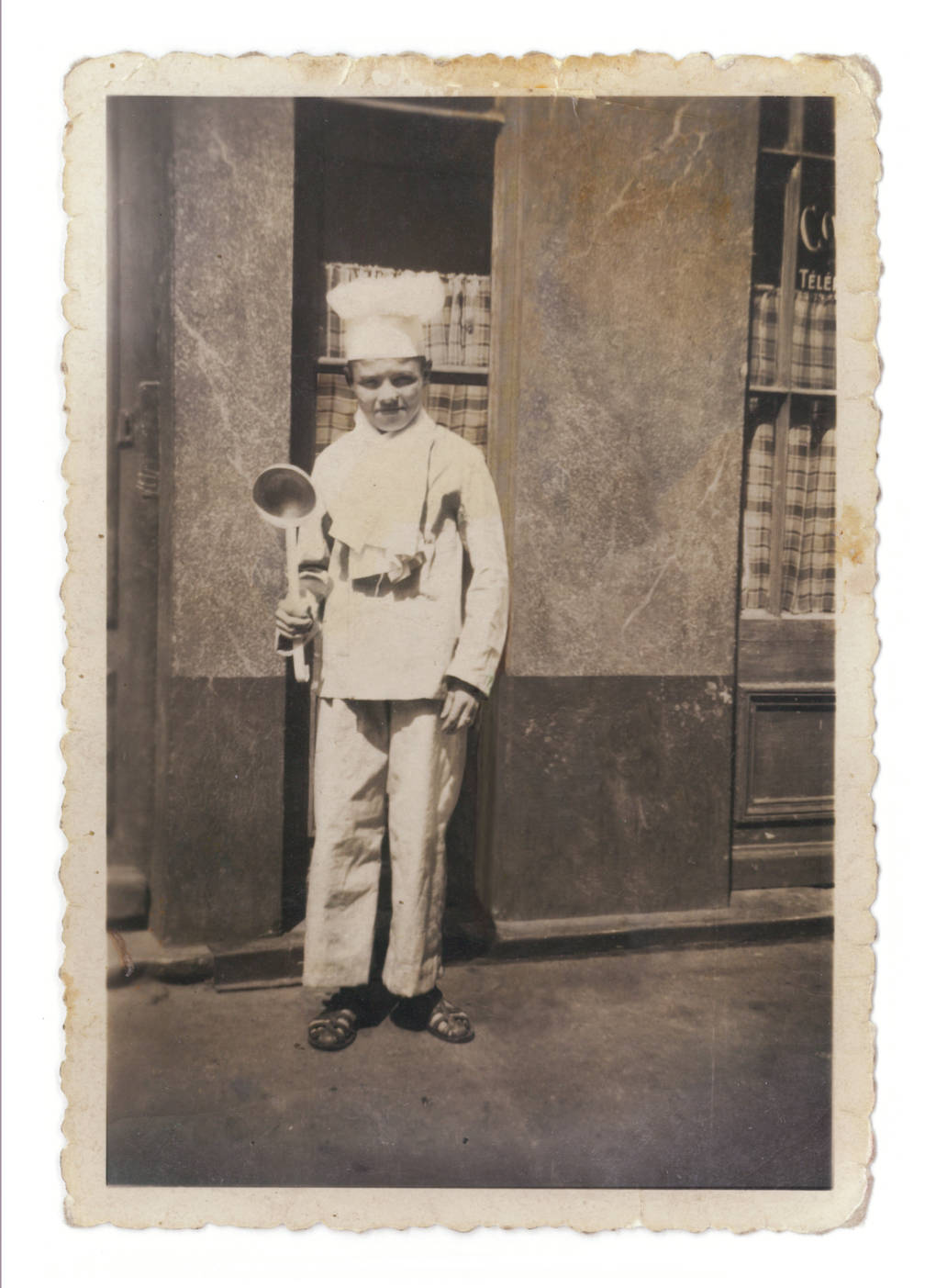

Pépin was no slouch when he arrived in the U.S. in the late 1950s. The film uses re-enactment, family photos and archival footage to cover the chef's early life. His first kitchen experience was in one of the family restaurants his mother opened after the Second World War, which the teenage Pépin parlayed into apprenticeships at some of the finest establishments in Paris. When he was drafted into the French navy, Pépin's work ethic and creativity eventually garnered him the position as personal chef to three French heads of state, including Charles de Gaulle.

Once his military service was over, Pépin headed to New York, landing a job at Le Pavillon, referred to in the film as the "best restaurant in the U.S." at the time. This was probably where the Kennedys came to appreciate his talents, so much so that, after winning the 1960 presidential election, they asked him to serve as White House chef. Another needle scratch. Pépin turned down the job! He chose instead to become Director of Research in the test kitchen for Howard Johnson's, the largest restaurant chain in the U.S. at the time. This move is key to the current celebration of Pépin as a distinctively American master. After serving in the world's great temples of haute cuisine, he decided to learn about mass production, creating recipes for Beef Bourguignon that could be produced in 500 gallon vats and putting the French back in French Fries. A decade later, Pépin left that post to strike out on his own, opening a very popular lunch spot in mid-town Manhattan, La Potagerie, which only served soup.

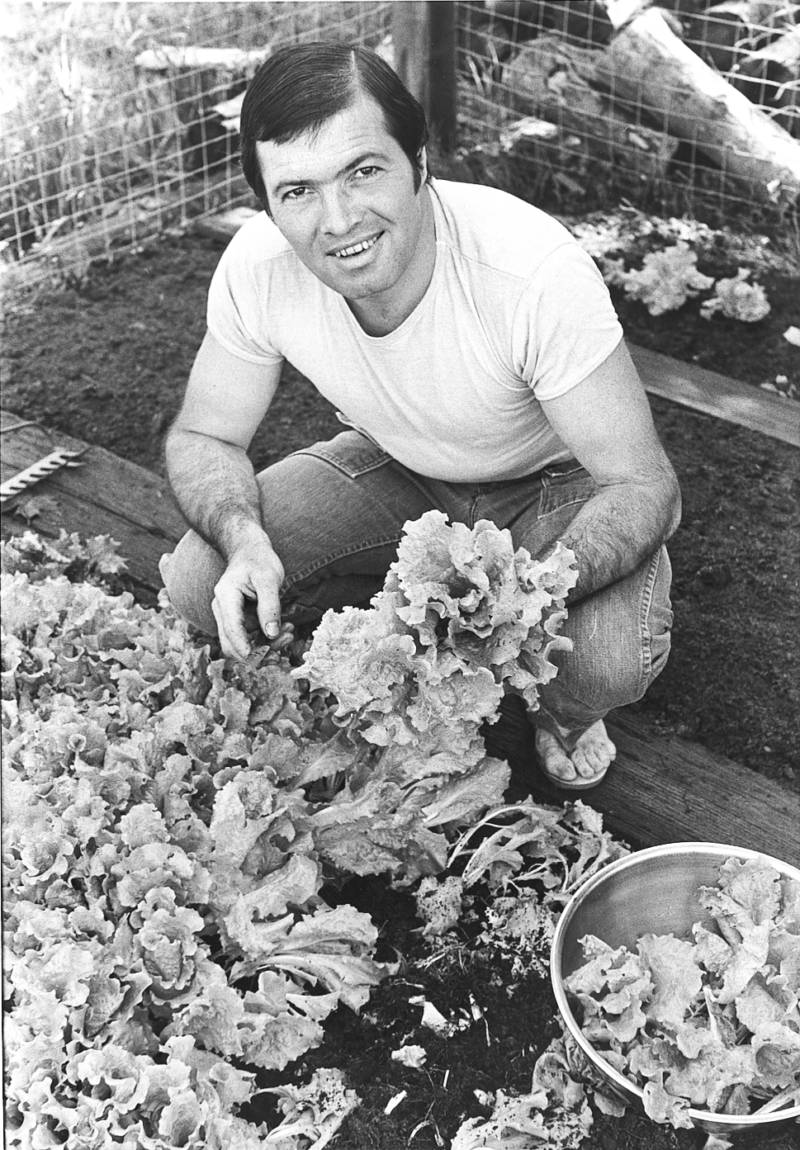

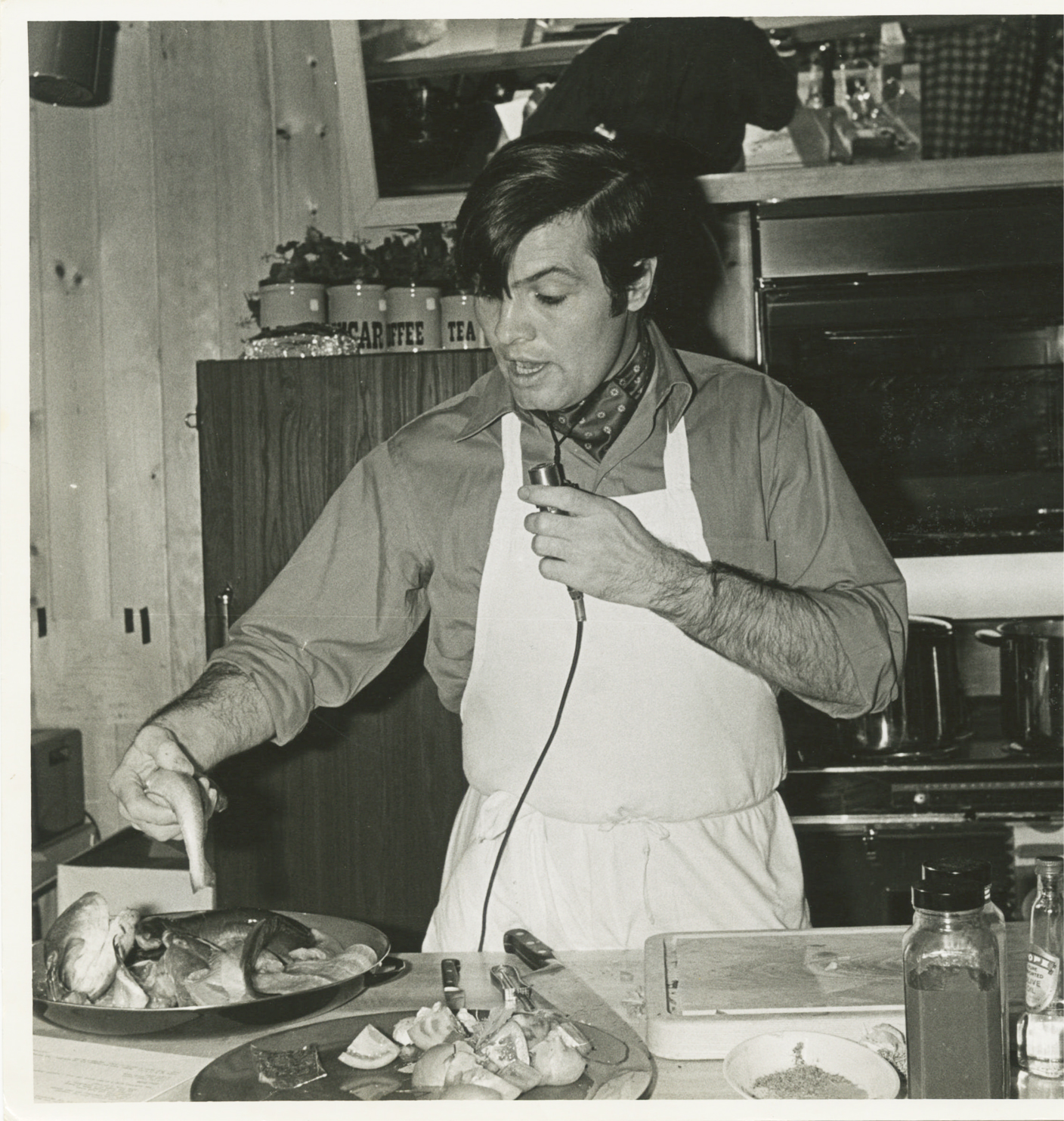

Eventually, the necessity arose for Pépin to reinvent himself once more. He wrote a cookbook, La Technique that taught Americans much-needed, from what he had observed, basic techniques for food preparation. He followed the success of that first book with another, La Methode; the two books were essentially about empowering the home cook. They were revolutionary at the time, demonstrating food basics through step-by-step photographic layouts. Pépin then hit the road, touring extensively to promote the work, which was the only option in an age before cable networks devoted exclusively to food. Exploiting his suave good looks, his natural charm and humor, not to mention that sexy accent, Pépin became the Tom Jones of cooking. Women flocked to his public appearances and swooned. This was the 1970s and the U.S. was pretty hot for all things French. Anthony Bourdain summarizes this idea with the quote that opens the film, "Before you have sex with another human being, you should be capable of preparing them an omelet to Jacques Pépin's standards the next morning."

So of course TV came calling, most particularly KQED, which produced -- with the very same Peter L. Stein at the helm -- Pépin's first successful cooking series for public TV. While he is extremely accomplished, Pépin makes cooking look easy, without -- paradoxically -- pulling focus from the centrality of work. His amazingly expressive hands communicate volumes -- mastery, wit, joy -- with every small gesture. His emphasis on technique is about developing know-how in your hands, which is communicated through the grace of his own movements. The chef's knife is a baton; the paring knife is a pen. Pépin creates art and music with food, orchestrating the meal as a communion between friends.

Pépin remained philosophically consistent on TV. With empowerment as his central goal, he utilized each half-hour segment to prepare a dish from start to finish, revealing how cooking is essentially technique and practice. He cemented this idea with another series wherein he taught his daughter Claudine to cook on the small screen.

But The Art of Craft is more than just one man's success story. Ultimately, it communicates, with the same breezy charm as its subject, the effect one person can have on a whole culture. This is the crucial idea that seems missing from today's America. We are a stew waiting for that distinctive ingredient that makes everything pop.