An unlikely pair of very American sandwiches, a Reuben and a PB&J, ushered in an evening of eloquently told tales illuminating many facets of Refuge at The Swedish American Hall on October 19. La Cocina’s latest storytelling performance of F&B: Voices from the Kitchen, featured impassioned words and searing images from more than a dozen writers, filmmakers, chefs and graduates of its incubator program.

To Heena Patel, an immigrant from Gujarat India who came to the U.S. 25 years ago, permanent refuge in America became possible thanks to a Reuben sandwich. She and her husband initially owned a flower shop and a liquor store. Even though she already worked 12 hours a day, when a neighbor inquired if she would manage his restaurant, she accepted, as it represented a pathway to citizenship. The only snag was that the menu of Hofbrau, the restaurant in question, consisted almost entirely of meat. And meat was something the vegetarian Patel had never even tasted. Nevertheless, this determined woman mastered the art of making the perfect hot corned beef, Swiss cheese and sauerkraut sandwich. On the proudest day of her life, when she became an American citizen, she told us she offered her thanks to “Reuben” who made it all possible. With support from La Cocina, she has now created her own business, Rasoi, cooking vegetarian Gujarati Indian dishes for the Ferry Building Farmers Market. But she dreams of a future food truck and restaurant; dreams, she admitted, that are full of stars (Michelin stars, that is).

Sharing the stage with Patel was American-born Geetika Agrawal, Senior Program Manager at La Cocina, whose Indian immigrant parents supported her Americanization by sending her to school every day with a “real American lunch.” Her mother lovingly packed her a Capri Sun, fruit, a granola bar and a green peanut butter and jelly sandwich until the middle of third grade when someone made fun of her green sandwich. (The mysterious green ingredient turned out to have been mint jelly, judged by her parents to be the most interesting of all the jam flavors in the market). After third grade, this novel culinary combo was shelved and almost forgotten. Until Agrawal, as a freshman in college, was shocked to find at her dorm’s dining hall, “lamb paired with a familiar old friend. I never imagined it as a condiment for meat,” she admits. “These moments of discomfort make me feel connected to my Indian-ness.”

Many of the evening’s stories shared tales of triumph. Award-winning author Andrew Lam delivered an ode to the resilience of pho, the noodle soup with the aromatic broth from his native Vietnam, which has spread out in a seemingly unstoppable diaspora to every corner of the world. It’s a “global pho-nomenon,” quipped Lam, who came to America at the age of 11, at the end of the Vietnam War.

The Vietnamese soup’s exact origins are somewhat clouded. But what’s clear is that its beef broth is perfumed with spices representing a mélange of foreign flavors, including Chinese and French ingredients, and is a testament to the resilience of its people. Pho, Lam informed us, is undoubtedly Vietnamese because it incorporates foreign influences – like its country, whose history includes being conquered by various foreign powers.

People adapt to survive but retain their distinctive Vietnamese identity, as does pho. Since expulsion from their homeland, Vietnamese people and their beloved soup have been flung across the globe. Pho can now be found in the furthest corners of the planet, from Antarctica to Ile de la Reunion, lovingly made by Vietnamese refugees who cannot imagine life without its comfort. The humble bowl of soup that represented their national treasure now appeals to their hope for posterity. While the people of Vietnam have scattered, Lam takes comfort in knowing something from his homeland has survived and the delectable aroma of broth with its pungent notes of cardamom, cinnamon, ginger and star anise is permeating the world.

Savanna Ferguson shared the story of immigrants, both human and vegetal; specifically how the humble potato saved and almost doomed Ireland. Potatoes were not native to Ireland. The tuber, originally from Peru, was introduced to Ireland in the late 16th century, at a time when food shortages were common. The potato quickly made itself at home in chilly Irish weather and rocky land. It was the perfect food: easy to grow, easy to harvest and easy to cook. And because it was almost nutritionally complete, the Irish populace thrived for generations. And then, in 1845, “potato blight” came to Ireland, its rot turning the tuber to mush. For five years, crops failed, killing one million people and forcing two million to emigrate. One million Irish immigrants came to the to U.S. to find refuge and changed our country forever.

In these days of heated debate over immigration, it is instructive to recall how much Irish immigrants were hated, prohibited from working, and described as” less than human.” These phrases seems depressingly familiar. Today, 10% of our country (34 million Americans) can trace Irish roots.

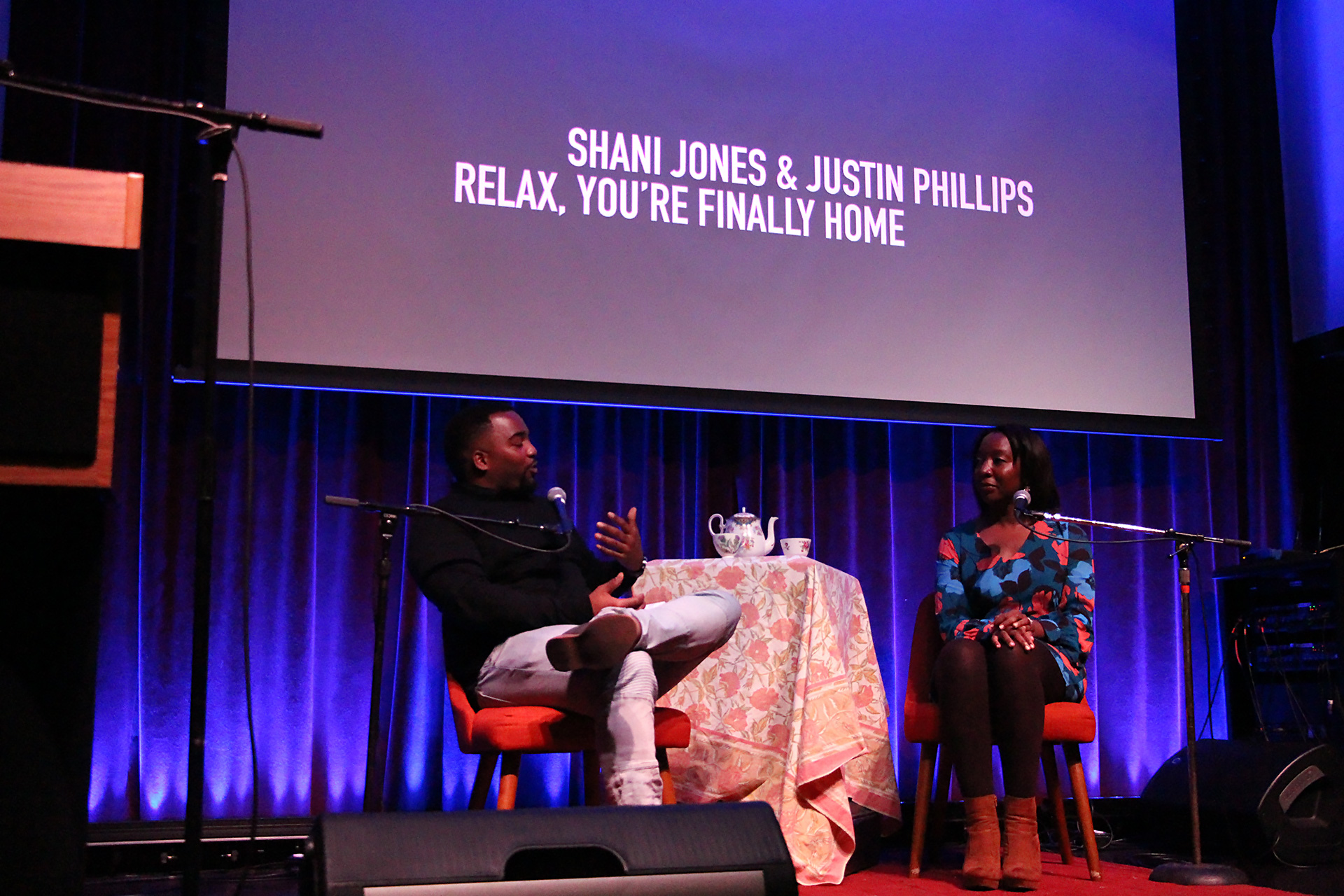

Next, we were treated to a conversation between Justin Phillips, food writer for the San Francisco Chronicle and Shani Jones, owner of Peaches Patties, a Jamaican food kiosk. They compared notes on their shared experiences and their reverse life trajectories: Phillips, a Black man, grew up in Alexandria, Virginia and recently moved to San Francisco, and Jones, a native San Franciscan, from a dwindling Black population, moved to Atlanta, Georgia to attend college at a HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) and returned home. They each related moments of cultural insensitivity in remarks from white people in both parts of the country such as, “You’re Black, but not Black-Black” or “You’re not like the rest of them!” Now that Jones has opened a kiosk to make and sell food inspired by her Jamaican mother, she has, in essence, opened herself up to even more offensive interactions, for example, being urged to speak with a Jamaican accent while serving her food. Their take-home-thought for the evening: there are culturally insensitive people everywhere. Phillips and Jones are two of only 50,000 Black residents in San Francisco, a city of 860,000. With these slim odds, Phillips cautioned the audience to take notice, “When you see two Black people talking about issues like this in public,” Phillips said, “It’s a unicorn moment.”

Other stories of refuge revealed tales of pain and loss. John Birdsall, an award-winning local writer, delivered a history lesson interwoven with personal travel tales exploring the refuge of queer safe spaces that exist around the world. He described how Berlin became the birthplace of queer safe space in the 1890s, when its bars and clubs flourished openly until the Weimer Republic came to power in the early 20th century. But when Berlin’s gay bars were closed down, Birdsall says, “the idea and the hope of refuge could not be extinguished.”

For Birdsall, his own travel stories “meant moving in a shadow world” of gay-owned B&B’s, frequenting bars and clubs in “gayberhoods” and queer enclaves – places that would supposedly shield their patrons from violence. But from the horrifying genocide of gays in Nazi Germany to the massacre at Pulse Night Club in 2016, it is clear that these supposedly protected zones of refuge cannot, in fact, promise safety.

The evening included dance and song performances plus short films interspersed between speakers. The most powerful example of the connection between food and refuge came in film clips from an upcoming documentary called: Soufra: A Recipe from a Refugee Food Truck, presented by producer Trevor Hall. He described Burj el-Barajneh refugee camp outside Beirut, Lebanon, where 50,000 people are crowded into narrow alleys and seven-story buildings within a one square kilometer space. In clips from the film, we see women in colorful hijabs chopping vegetables, chatting, cooking and laughing. What is not immediately apparent is their status as “prisoners,” since they lack the financial and political means to leave the camp.

In another clip, we meet Mariam al Shaar, an entrepreneur who was born and has lived her whole life in Burj el-Barajneh. Yet Al Shaar is determined to harness the energy, resourcefulness and creativity of the women of the camp through their food. She is a social entrepreneur with a vision and a plan to uplift the lives of the women through cooking and selling their food. Since the women come from various backgrounds, Palestinian, Syrian, Egyptian and Iraqi, the process includes them teaching each other classic dishes from their cultures. The story of Mariam al Shaar illustrates the power of food to bring people together, empower them and create refuge where there is none. This documentary feature film will be coming out in November.