During opening hours at San Jose restaurant Orchestria Palm Court, more than a dozen instruments combine to create a soundtrack of ragtime and early 20th century jazz. But don’t expect to find musicians seated at the piano benches or rosining their violin bows. Orchestria’s vintage pianos, violins, pipes, bells and drums make music all on their own.

Eat & Drink Like You're in the 1920s, Two Nights a Week

“Quirky” is the word most often used to describe this Continental European-style restaurant in San Jose’s SoFA District, says owner Mark Williams, but it’s not just the stable of mechanical music machines that encircle the dining room and stand sentinel on the upstairs balcony that has earned the restaurant its moniker.

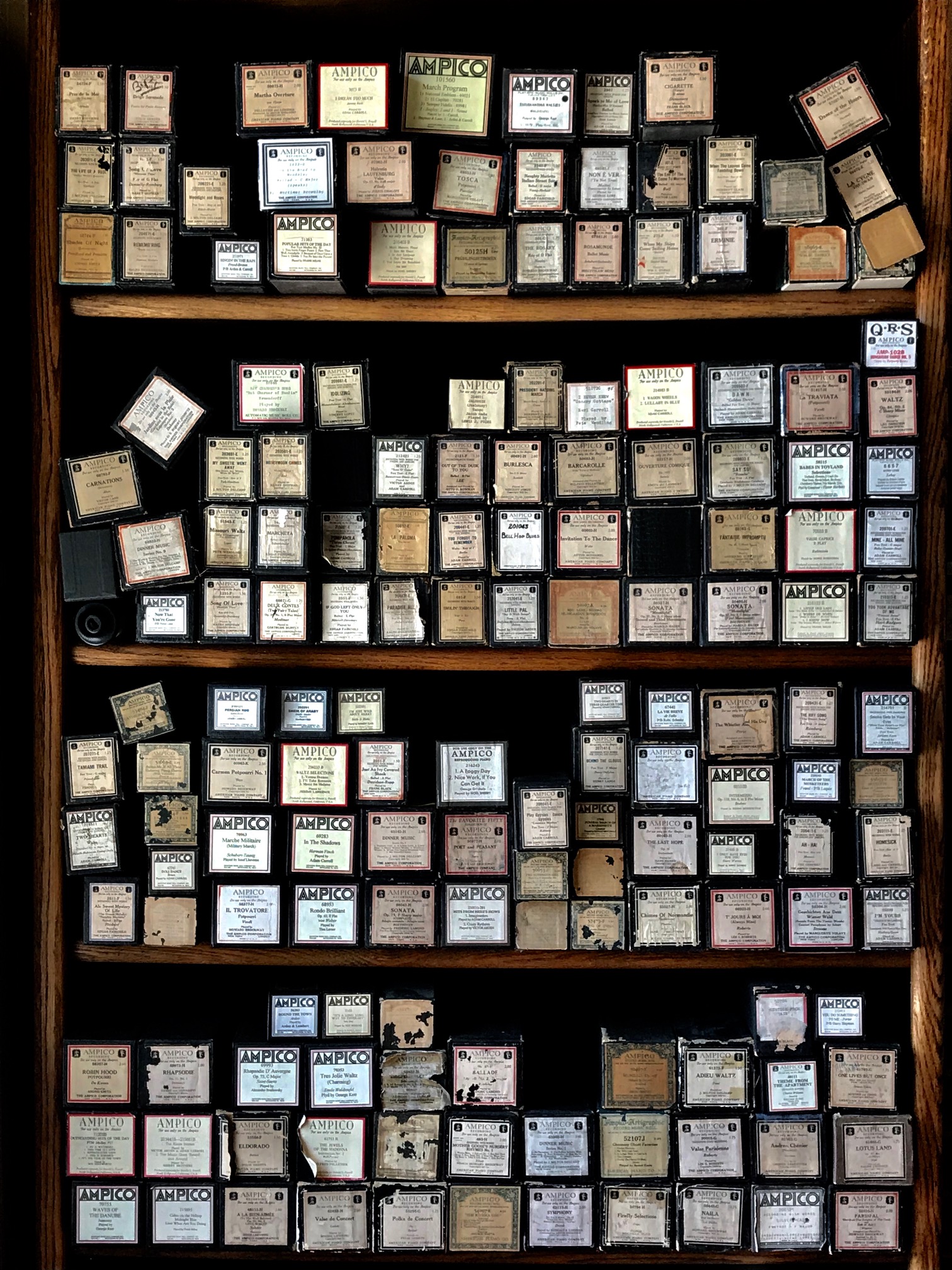

The brick-walled, turn-of-the-century warehouse is full of nods to early Americana, from a soda fountain churning out Prohibition-era fizzes like black forest phosphates and raspberry ambrosias to an old-school phone booth which patrons are encouraged to use for any cell phone chatter. Bookcases around the restaurant are stocked with hundreds of player piano rolls and Art Deco posters and Tiffany-style lamps are arranged throughout the space.

It’s the self-playing music machines, though — the player pianos, the Wurlitzers, the phonograph jukeboxes — that really make the Orchestria Palm Court stand out.

Though relatively rare today, for a brief period in the early 20th century, bars and restaurants everywhere were stocked with a mechanical music machine. It was the first time in history that recorded music became accessible to all. Now that same music, all-but-forgotten novelty songs and syncopated dance tunes that were hits in their day, are resurrected within the walls of the Orchestria.

Music enters a new era with the help of the earliest computers

Before the late 19th century, music only existed when musicians played it. So when early player pianos, or Pianolas, and phonographs began to appear, they were a massive technological shift. The first fully-pneumatic commercial player piano arrived in the 1890s. Using pressurized air, the piano contained concealed mechanisms that turned a paper roll printed with perforated holes. The distribution of the holes and the speed of the turning roll determined the tone and melody of the song.

Some of the bigger machines could play rolls that contained up to ten songs, strung together one after another, while smaller pianos could only play rolls containing a single song at a time.

After World War I, the popularity of the player piano skyrocketed, ushering in the “Jazz Age” of the 1920s. “The early hot music was the cakewalks and those morphed into ragtime,” explains Williams, “Jazz started coming in the mid-teens and by the ‘30s they were getting into swing.” But along with a change in musical style came a change in technology. As quickly as the pianola had risen, it fell back into obscurity.

“Basically this era was dead by ‘31,” Williams continues, due to the one-two punch thrown by the crash of the industry along with the stock market in 1929 and the rise of new methods of electrical amplification and radio.

For decades America’s leftover Pianolas gathered dust in basements and attics and warehouses around the country but, following the 1973 release of The Sting, a Paul Newman and Robert Redford film with a ragtime soundtrack, collectors developed a renewed interest in the vintage machines along with early jukeboxes like the Deca Disc phonograph which contained five records and the Electramuse which could play up to ten records. Williams was among them.

A small-time collector with a few player pianos to his name, Williams was inspired to enter the restaurant world in order to create a showcase for the musical technology that was once an essential aspect of eating out. An electrical engineer by trade, a job at which he still works 40 hours a week, Williams had become jaded with the start-up culture of Silicon Valley.

“All your successes are so fleeting,” he says.“The point of the [restaurant] was to acknowledge that all the stuff you’re doing now, something preceded it. This technology, these were the early computers.”

The mechanical instruments and players that now call the Orchestria Palm Court home have come from all over. Some, like the Imhof & Mukle “Commandant 2” Orchstrian (circa 1920), a high-backed wooden beauty with piano and violin pipes and percussion instruments hidden inside, were donated. Others were purchased by Williams and his partner. The Violano-Virtuoso Player Violin, a highly-advanced invention dating to around 1925 and Williams’ favorite machine, was acquired from the widow of a hobby collector in Southern California.

Pianolas can be purchased cheaply Williams says — you can even find them on Craigslist for free — but restoring them to playing condition is often a complex and expensive task.

Classic foods from a simpler time

Music may be the soul of the Orchestria Palm Court, but it’s the restaurant’s food that is at its heart. Orchestria produces rich, classic European dishes like Austrian goulash, chicken breast saltimbocca, and butternut-Marsala pasta made with organic produce and dairy, free-range chicken, and grass-fed beef. There’s no microwave or deep fryer in the kitchen and the menu changes weekly to feature fresh, seasonal foods.

The quality of the food is, in fact, so important that, when the restaurant was struggling to fill its seats after opening in 2012, Williams chose to cut its hours to two evenings a week rather than compromise ingredients.

Beer and wine are also on order but it’s the fountain drinks that really make the restaurant’s beverage program unique. “In the ‘20s, soda fountains were all the rage because of Prohibition. They came up with all sorts of varieties and the stuff tastes so different than what you get out of a can. We’ve lost a lot there,” Williams says. Indeed, this may be the only place in the Bay Area where crafted sodas like the poppy dew, a sweet, tart orange drink, and the New York-style chocolate phosphate still appear.

From its carefully crafted menu to its lovingly restored 1910 digs, there’s a nostalgic authenticity to the Orchestria Palm Court. The 4-bit computer code technology used in the Pianolas and early jukeboxes here didn’t just form the foundation of early recorded music, but the foundation of early Silicon Valley, too.

Still, while the rest of the Bay Area is looking for the next big breakthrough, Williams is happy with his vintage machines. They’ll keep singing for their supper every Friday and Saturday night for the foreseeable future.

Orchestria Palm Court

Website

27 E William St.

San Jose 95112

Open Friday & Saturday, 5:45-8:30pm