Back in April, when grocery shopping seemed especially precarious, I bought a 50-pound sack of flour about the size of the bag of kibble my Labrador goes through each month. Over the past five months, I’ve become proficient at feeding my sourdough starter and shaping loaves, and I find baking soothing. But we can’t live on bread alone; I’d have to find another use for all that flour.

Author Beth Bich Minh Nguyen, who relocated from Berkeley to Madison, Wisconsin, started making noodles back in April. Yaki udon is one of her kids’ favorite dinners, but the noodles were unavailable in stores. Since she often bakes cakes and pastries and has cranked out pasta in the past, she decided to try making the Japanese wheat noodle. “Udon is easier and faster, especially since I use my stand mixer to knead the dough,” said Nguyen, who couldn’t believe how easy and delicious it was. “The texture and chew! Also, the dough freezes well. So I’ve made udon numerous times now and may never go back!”

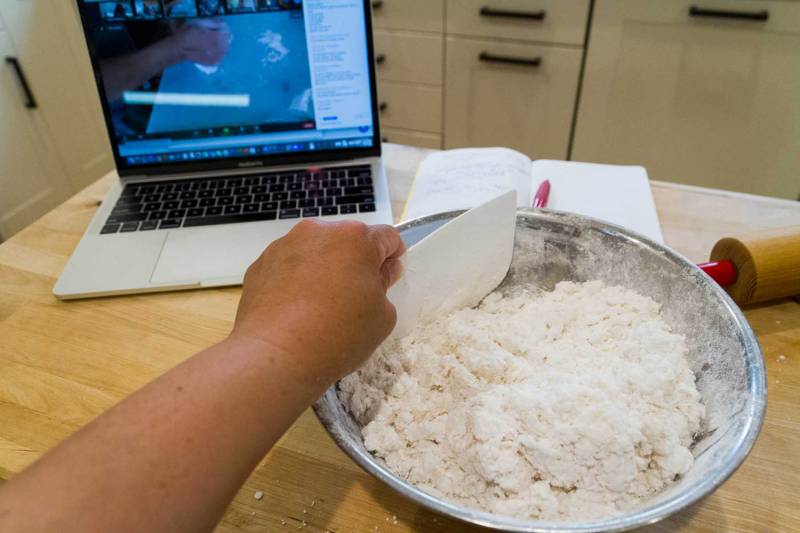

Recent heat waves were the breaking point for me. Turning on the oven was a non-starter. Maybe it was time to try making noodles?

First, I checked with Sonoko Sakai. Before the pandemic, she was teaching in-person workshops in the Bay Area every two months—at the San Francisco Cooking School, Japanese Cultural Center, Pollinate Farms in Oakland and SHED in Healdsburg (which has since closed)—as well at her home in Los Angeles. Since shelter-in-place, she’s taught three soba webinars. Online teaching has posed some challenges; usually she provided specialized knives and rolling pins, as well as buckwheat flour from Japan that is especially fresh and finely milled for soba. Now, she mails ingredient kits to students and has adapted her technique for everyday kitchen equipment, producing a more rustic, homestyle soba. “Just make a dough and make a ball and roll it out and cut the noodles. Keep it really simple,” she explains, adding, “Soba is a finicky dough because it’s gluten-free.”