If there's one cuisine that I'd love to be able to cook like a native at home, it would be Moroccan. Why? For the seductive spicing that scents the kitchen like a bazaar; the dried apricots and dates nestled up lush and luscious next to slow-cooked lamb; the crisp brik pastries; the fiery smear of harissa; the unexpected matches of sweet and savory, even the delicate, gold-rimmed glasses poured theatrically full of hot, achingly sweet mint tea out of the held-high spout of an intricately decorated silver pot.

I had my first Moroccan meal—a platter of couscous piled with meat and soft-cooked vegetables, ladled over with flavorful broth and shared by everyone at the table—in a small, cozily dim neighborhood restaurant in Paris in 1983. I was a teenager, and no stranger to New York and New Jersey's various ethnic restaurants, thanks to my culinarily-adventurous parents, but the flavors of North Africa were utterly new to me. Couscous and Other Good Food from Morocco, which brought descriptions, at least, of tagines, couscous, preserved lemons, and ras el hanoot to American kitchens (getting authentic ingredients was something else), had been published ten years before, but author Paula Wolfert's caftan-wearing bohemian taste hadn't wafted to our corner of the East Coast yet. I had to get to France, with its large post-colonial population of North Africans, to taste scorchingly hot merguez (lamb sausage) and the pigeon pie, called b'steeya, whose savory filling was wrapped in shatteringly crisp, sugar-dusted pastry leaves.

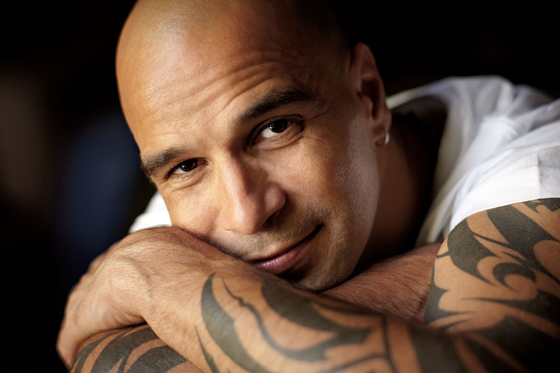

Now, decades later, San Francisco has its own mini-neighborhood of inexpensive Moroccan and Tunisian restaurants along a five-block stretch of Polk Street. And then there's Aziza, the swanky destination with the unlikely Outer Richmond address, as much like these casual couscous joints as Kokkari is to a gyros shop on Telegraph Ave. Run by Mourad Lahlou, the tattooed, Moroccan-born chef who came to San Francisco in 1985 to go to college at SF State, Aziza is a contemporary restaurant first, with Moroccan roots but a menu dedicated to modern techniques rather than classic interpretations. Because, as Lahlou writes in his new book, Mourad: New Moroccan, why shouldn't Moroccan food evolve, just like California cuisine has? As he writes about his childhood memories of growing up in Marrakesh with a large extended family,

But the thing is, I don't long for that world. I cherish it, and I cook from it every day. And so, dish by dish and year by year, my food evolves. I started at Kasbah [his first restaurant, in San Rafael] with a somewhat obsessive attitude about showing people real Moroccan food, done the authentic way. But there we were in California. It's just not possible. The ingredients are different—even the ones flown in from Morocco don't taste the same by the time they arrive...So, before long, I was doing the Moroccan version of what so many inventive northern California chefs have done. I adapted what I knew and loved to make it work with the beautiful ingredients I can get here, and then just followed my nose, my heart and my palate."