For many educators, teaching Martin Luther King, Jr.’s keynote address from the 1963 “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom,” which is widely known as his “I Have a Dream” speech, can be daunting. The speech is monumental for its impact, and it is often the main avenue teachers use to teach about it’s author. Up until this year, I have always cobbled together snippets of the speech with additional resources to teach the main points. I would use video of John Lewis’ speech at the 1963 march to contrast the tone and content. I would use the story of George Raveling as well as oral histories of other key figures in the march to help my students understand King’s ideas. However, this year I came across the interactive, multimedia resource “Freedom’s Ring,” and I feel much more empowered to do justice to King’s famous speech. “Freedom’s Ring” is going to play a major role in every US history and government class I teach from here on out. It’s that good!

“Freedom’s Ring” was supported by The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford, which is run by Dr. Clayborne Carson. Dr. Carson has been the director since 1985 and was personally chosen by King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, to run the Martin Luther King Papers Project. Dr. Carson has curated King’s papers and expanded their accessibility. “Freedom’s Ring” is just one of many great resources the Institute has built under his direction. For teachers, The King Institute has online lesson plans, The Liberation Curriculum, the Martin Luther King Encyclopedia, as well as the King Papers, all of which are accessible online. In other words, “Freedom’s Ring” is just the tip of a gigantic iceberg.

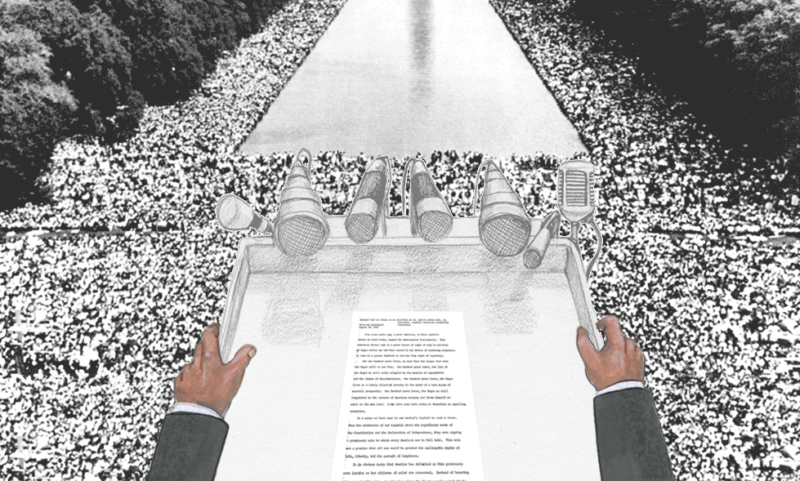

But “Freedom’s Ring” is an especially powerful resource because it covers the whole speech in an interactive and multimedia format. It presents the complete speech via audio recording, complemented by prominent text that matches the audio. It also includes animated visuals behind the text which interpret the speech, as well as links in the text which lead to all sorts of rich resources that students can use to gain a better understanding of the speech’s context.

For example, the opening scene of the speech is pictured below with the word “today” appearing as a blue hyperlink.

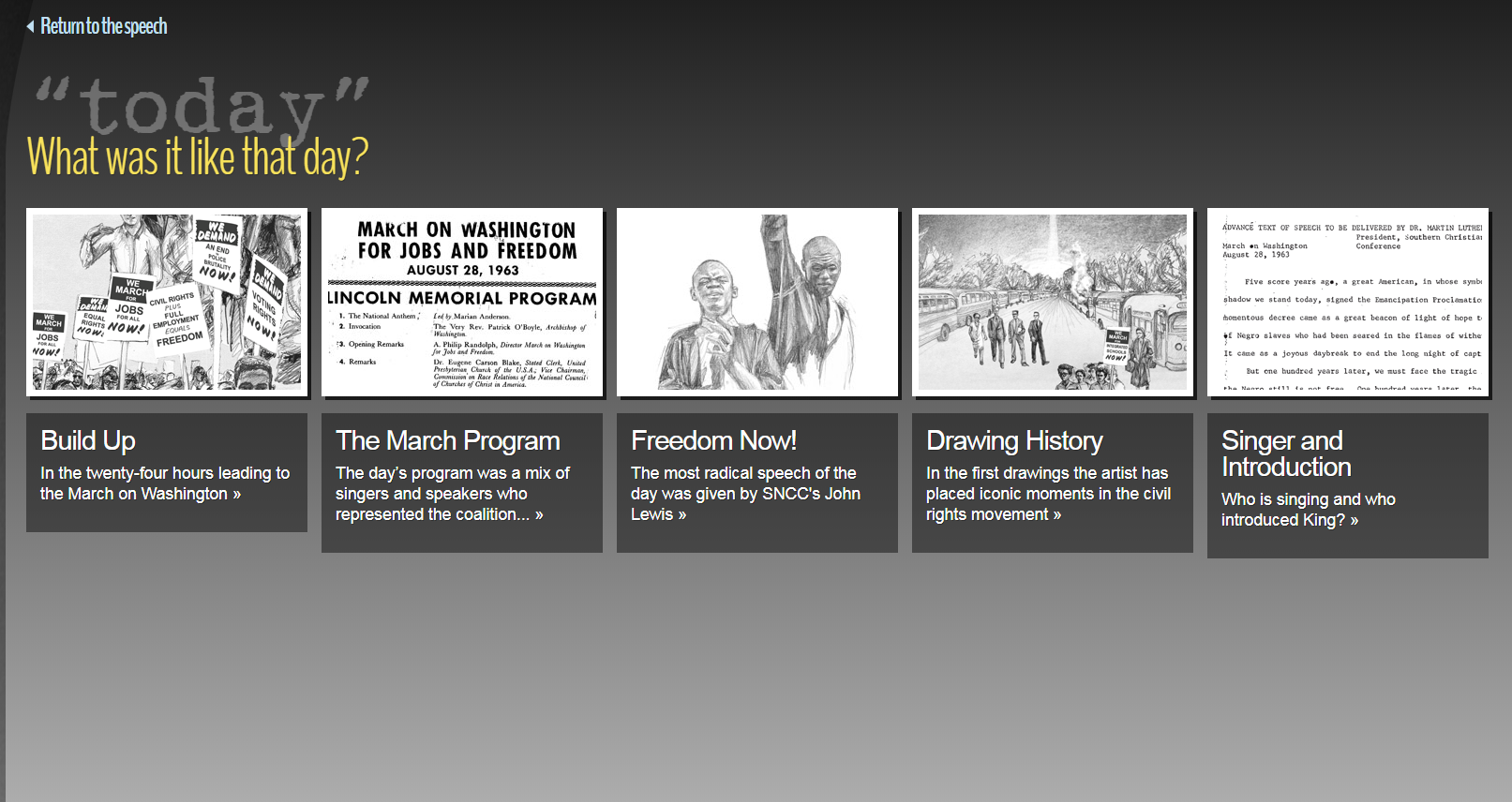

If the viewer clicks on the link, they are taken to the following screen:

Each of the visuals in this window are clickable resources which reveal different ideas, concepts, issues and perspectives that pertain to this section of the speech. In this case, this link covers the historical build up to the March on Washington.