As a Social Studies teacher, I struggle with the current political climate and the power and limits of the Internet and modern media. Students show up to class and eagerly show me the latest political meme. I appreciate their enthusiasm for the subject, but I always ask them where the meme got the information. Cite me a source, please. Next period, the situation repeats itself. At times I feel a little bit guilty as I puncture a student’s earnest attempt to connect with me through a medium they understand, but teaching them the fundamental literacy skill of citing sources takes precedence.

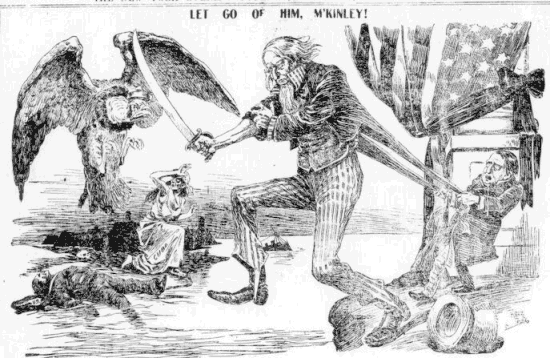

When it comes to fundamental literacy, I mean fundamental: citing sources (even in memes) is just one component of the broader literacy skills that I emphasize with my students of finding and identifying information. When it comes to text, we start with the information hierarchy: headings, subheadings, captions and visual aids. They learn how to locate information in textbooks and encyclopedias, as well as in primary historical sources.

These skills transfer over to other forms of media, too, such as maps: find the title, the legend, the compass rose and the scale. More importantly, they learn confidence. My next step is to transfer these fundamental literacy skills to the Internet. I treat websites, applications and memes just like any other text. We look at how the text or information is organized, pay attention to clues that indicate whether some piece of information is sponsored content or clickbait and play “find the author.” Nobody is allowed to respond to a question about where some information came from with the brainkiller phrase “the Internet.”

I have struggled with how to teach students media literacy skills, especially during and after the 2016 election. Friends of mine on both sides of the spectrum spouted off talking points that I had just seen on social media—often without double-checking or citing their sources. The lesson I learned out of these experiences was that we all need to go back to fundamentals. I felt stressed out from being bombarded with memes all day, and I saw the same stress affecting my students, so I decided to try and fight fire with fire and harness memes for educational purposes.

To further help my students explore literacy fundamentals when it comes to media, I decided to have my students approach memes, but this time as creators. In Civics students had to utilize their political knowledge to make the best political point. They used widely recognizable meme pictures such as Bad Luck Brian and Minor Mistake Marvin and came up with their own captions. When I first ran this project in 2016, I used memeful.com, but since then there has been an explosion of new tools. The rules: be school appropriate and be creative, and make a serious political point in a humorous way.