It seemed like a good lesson idea: A student-created interactive timeline to use as a study guide for their final test. On paper, it looked great. Students would have a chronological reference and have to identify and summarize significance in their own words showing deeper understanding. Adding images to the timeline would help students remember the information with a visual association. And the activity would integrate a new technology application. Yet, I have never received so many complaints about a project than I did with this one. Maybe it was the fact that it was the first final exam for freshman and they were unfamiliar with how to study for a cumulative exam. Maybe it was the fact that the students struggled with technology (yes, even in this day and age). The bottom line was—it flopped.

As I reflected on the lesson, I realized I didn’t follow my own rule of thumb for using technology in the classroom: technology is not meant to supplant, it’s meant to enhance. The interactive timeline didn’t enhance, it just supplanted the old school fill-in-the-blank study guide.

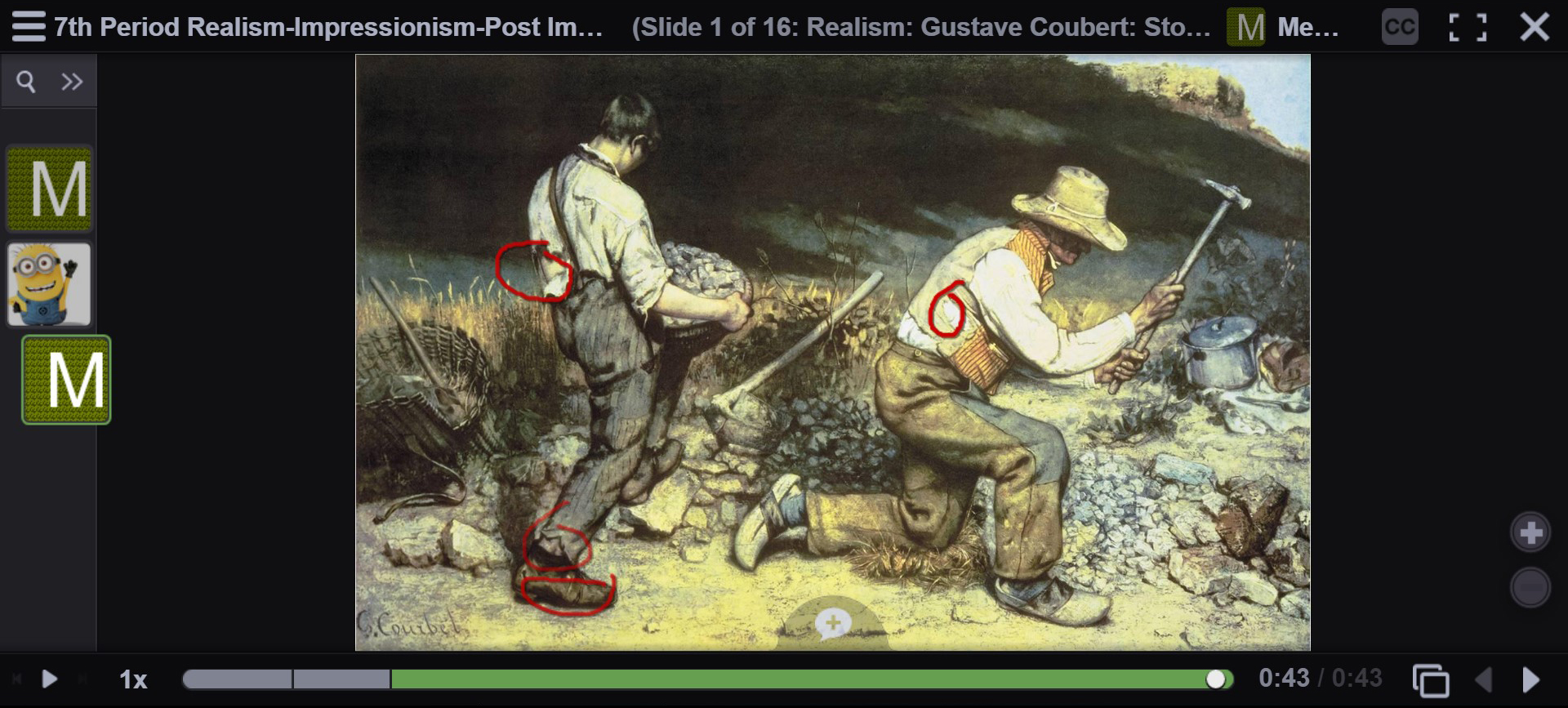

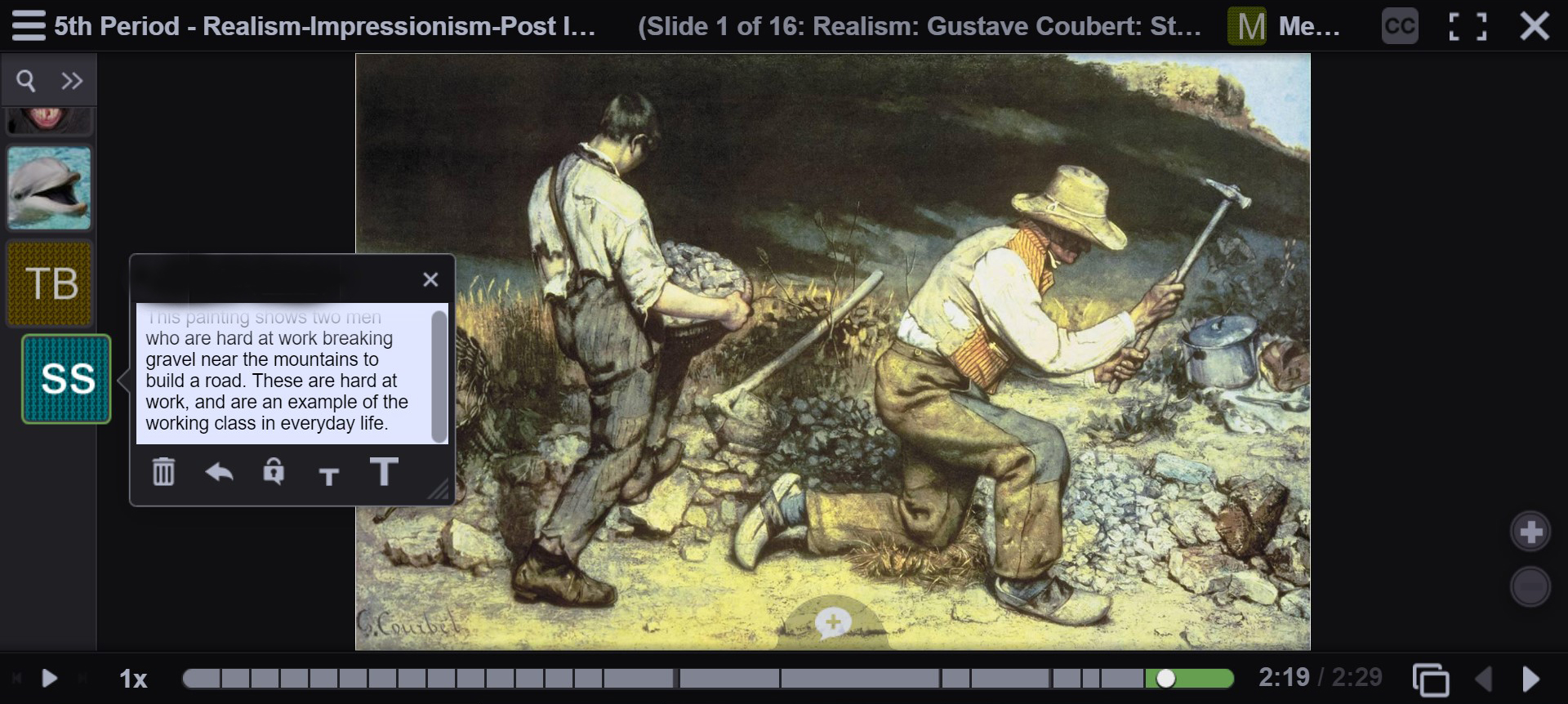

I first learned this lesson long ago when teaching 10th grade World History. I had used a Teacher’s Curriculum Institute cooperative learning activity where student groups created posters of the main people and events of the French Revolution. Students presented their posters, offering both verbal and visual chronology of the French Revolution as well addressing its causes and effects. In following years, students also created posters for the Glorious Revolution and the American Revolution, which we placed on the walls around the classroom. Students constantly referred to the posters as we covered each revolution unit. In the culmination activity, students used the posters to document similarities and differences between the political revolutions of the 1600-1700’s. When we discussed the Revolutions of the 1800’s, we were also able to look at the back wall and see if the revolutions in Latin America or Central Europe had similarities to the revolutions we had already covered. The lesson was a “keeper.” But it didn’t work with technology.

When our school piloted iPads for some freshman classes, several of my colleagues tried having students use the storybook app to re-create the poster activity of the French Revolution. Doing the project on an application was just supplanting the analog activity with technology, not enhancing the learning. In fact, in this case, it did the opposite: it took away from the learning. Students weren’t in groups discussing the event and working together to visually represent it. While they could have worked on the app in groups, there were issues that made it difficult: the visual story was locked on only one student’s computer, visible only to them and their teacher. And even if the story was presented to the class, it couldn’t easily be referenced during the year like the posters on the wall.

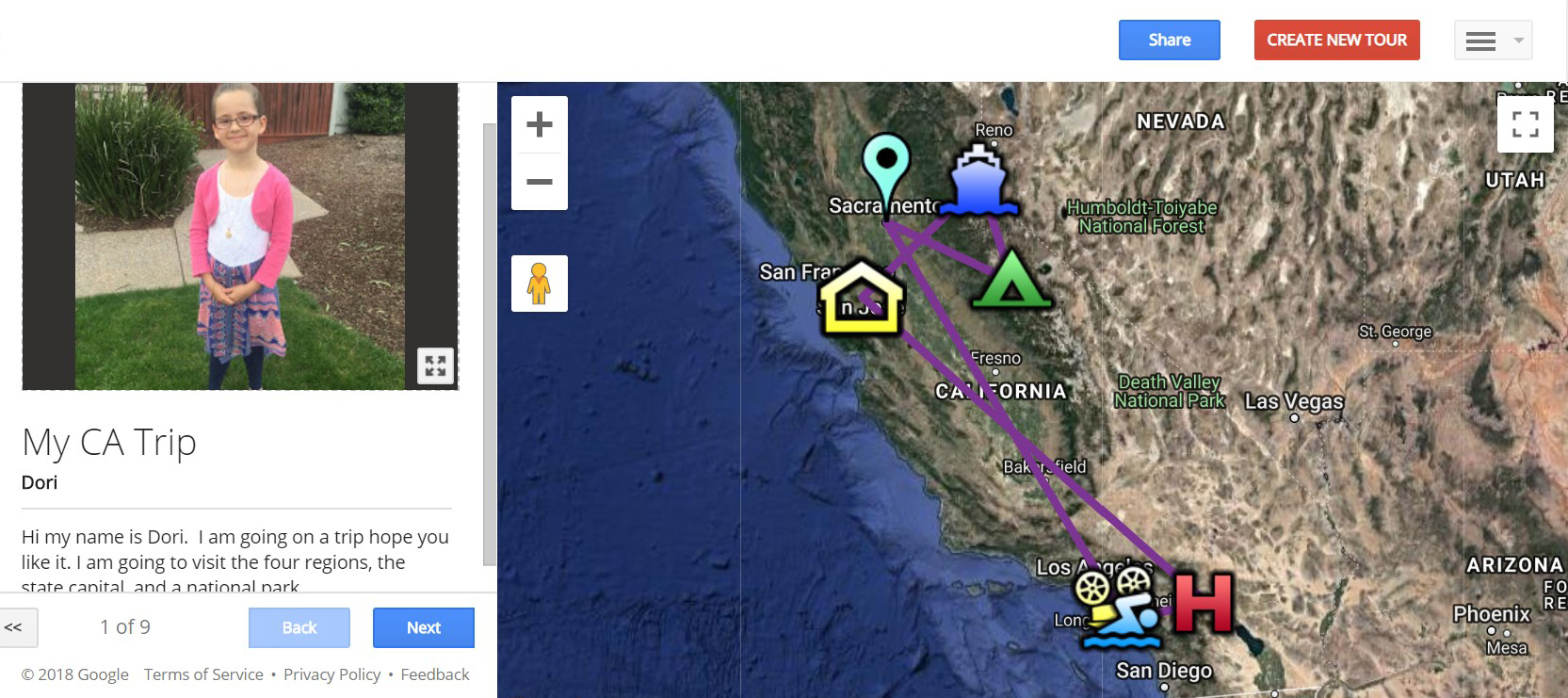

However, the digital timeline assignment did work for Julia Gossard, Assistant Professor of History at Utah State University, who had her students in “Foundations of Western Civilization” create a digital timeline of the history of food. Dr. Gossard used the online timeline assignment to offer students a different lens to view history, analyzing the economy, politics, and society at the time through what and how people ate. The food timeline strengthened students’ research skills, asked them to work collaboratively in teams, and had them utilize technology to present the material.