“What do you do exactly?” This is one of the questions I get asked all the time as a Product Manager. Even though Product Management has recently become a key role in technology firms, it’s still a mystery to many people. We are responsible for the strategy, development, and overall successful launch of digital products, serving as a bridge between the various groups involved in the product life cycle, including customers, engineers, and executives. One thing we do a lot of is sharing best practices, frameworks and processes – this act of sharing data and knowledge is how we are growing as an industry so quickly.

I was personally hella juiced to be able to participate as a KQED staff mentor this season with KQED’s Youth Advisory Board. We got to dive into the product lifecycle we use for our apps at KQED, and I got to share what I do with Hannah, my Youth Advisory Board mentee from California Virtual Academy Sonoma. It’s essential to bring in the voice of the next generation as we frame what is important to build for all of KQED’s community. Thanks to this experience with Hannah, I have a few ideas ready to take back to the mobile app team to see if we can turn them into reality in our app. Our process was guided by the principles of Design Thinking – focusing on problem-solving and creating a great experience for our users – for impactful product development. I hope you enjoy Hannah’s reflection on our process where collaboration, empathy, and iteration reign supreme.

Hannah’s Reflection

Step 1: Empathize

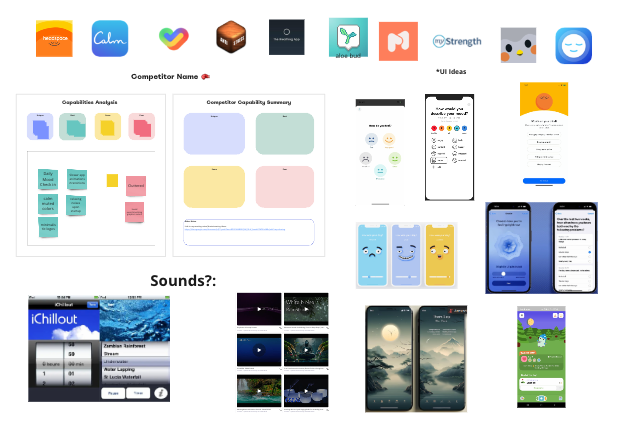

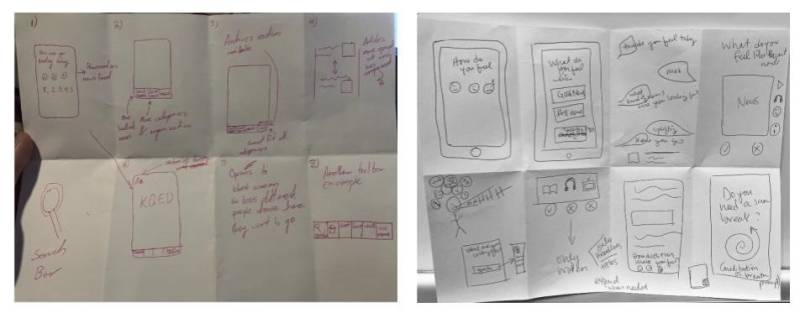

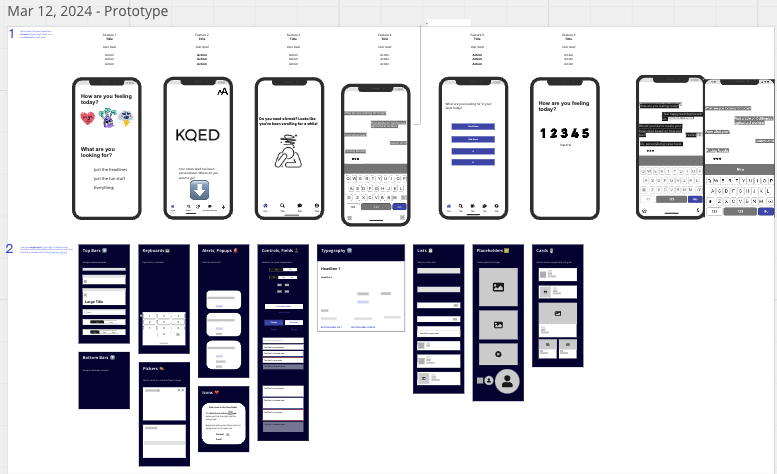

To begin, we first had to understand our user base. Most listeners and users of the KQED app are middle-aged and older. In order to attract new audiences and grow KQED’s user base, we researched topics and approaches that would be relevant to younger generations. Mental health is a pressing matter among today’s youth, so we figured that one way to cater to their interests would be to implement a mental health check-in upon opening the app. Users could rate how they are feeling and the app would curate their news based on the rating. For example, if a user gives a lower rating, their news feed would show more uplifting stories and avoid potentially triggering ones. We researched features from popular mental health-oriented apps, such as the mood check ins from Headspace and Calm, to get a sense of what is available today for mental health and where there is still a user need to fill.