Transcript of Mina’s Interview with Alice Wong:

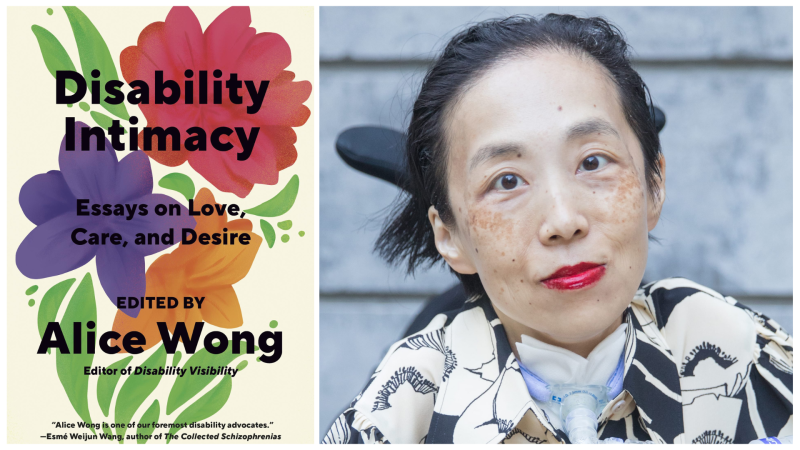

Mina: Welcome to Forum, I’m Mina Kim. Shortly after writer and disabled activist Alice Wong got the green light in 2022 to pursue a new anthology all about intimacy, she had a series of medical crises. She was hospitalized for a month and emerged from the intensive care unit profoundly changed. Wong has edited multiple anthologies, including “Disability Visibility” and “Low and Slow,” a series of food writing by disabled people. And she described working on “Disability Intimacy: Essays on Love, Care and Desire” as a “critical lifeline, just like the breaths of air from my ventilator and liquid nutrition flowing into my feeding tube.” In a pre-recorded interview where Wong uses a text to speech app to respond, I asked her what editing the anthology in the aftermath of hospitalization, meant to her.

Alice: It’s amazing how much I have changed in the last ten years and even in the last two years when Disability Intimacy first came about. My memories of what happened two years ago have been very hazy, time folded like a piece of origami into an abstract alien shape. The book proposal for Disability Intimacy was accepted in early twenty twenty two before I was hospitalized that summer which turned out to be the most horrific and traumatic time of my life. Intimacy, as a concept, was something I wanted to explore and share with the world because I was irate and tired of the ableist tropes and stereotypes about disabled people who have sex. There is so much disabled wisdom and creativity that completely expands and blows up conventional understandings of intimacy. When I became seriously sick that summer, almost dying multiple times, I ended up with a radically different body. I experienced such gentle waves of community care and love. I was at a very low point and needed so much help. My friendships became more intimate and that deepened my understanding of intimacy. As I was trying to recover, while having to deal with all kinds of new health-related problems, frustrations, and disappointments, I worked on the book which was a revelation. Editing an anthology is like wrangling a bunch of magnificent cats. It’s so different from writing on your own. With intimacy as the theme of this book, the contributors put such tender care into their work. I delicately edited these essays with sensitivity, knowing how many people put their trust in me. I believe the relationships I built with the contributors during the editing process facilitated some magic that helped their pieces blossom. Working on this book was such a joy and a part of my healing process. Being creative, collaborating with others, and building something beautiful together, gives me life. Editing this collection and the Low and Slow series for Eater dot com gave me something to focus on, it was a lifeline in the midst of pain and suffering. Overall, it’s brought me a sense of gratitude that I’m still alive and have the privilege to work with so many talented people.

Mina: You write about Googling the phrase “disability intimacy” when you started work on this – and you said the results were “disappointing and pathetic” and made you go “Ewwwwww.” What made you go Ewww?

Alice: The Google search, if that is a barometer of mainstream social attitudes and values, turned up articles on stereotypes, stigmas, sexuality, sexual abuse, and sexual dysfunction. Stories about and by disabled people on “what it’s like” to date, have sex, or be in a relationship abounded. I rolled my eyes so hard at them because it’s so basic, ableist, and vanilla if you know what I mean. Disabled people are so innovative and creative in the ways they express intimacy because we live in an ableist world with such narrow conventional ideas of intimacy. To me, intimacy is more than sex or romantic love. Intimacy is about relationships within a person’s self, with others, with communities, with nature, and beyond. Intimacy is an ever expanding universe composed of a myriad of heavenly bodies. It’s my hope that readers of my anthology will question their own ideas of intimacy and their relationships with it.

Mina: This portion of this hour is pre-recorded, and you’re speaking to us through a recording from your text-to-speech app. What’s your relationship with this voice specifically?

Alice: So there’s the physical voice, speech and sounds we make with our body, and voice in the broader sense, about your perspective on the world. I detest advocates who say they are a voice for the voiceless because everyone has a voice, it just might be in a different medium and it’s our responsibility, if we actually care about diversity, to make an effort to listen and meet people where they are. And this is especially true for radio. I continue a voice through my writing as a columnist for Teen Vogue and other projects but my physical voice no longer exists since I now have a tracheostomy in my throat that is connected to a ventilator that I am dependent on twenty four seven. I miss my physical voice. I was a really funny, witty speaking person. I wish you could have known me a few years ago Mina but I can’t go back, I can only go forward in this disabled cyborg body that is still alive and kicking butt. The way I express myself will never be the same. I would characterize my relationship to voice as fraught. I’m thankful to live in an era where I have an array of assistive technologies I can choose from and at the same time I struggle being heard, seen, and respected in my new nonspeaking corporeal form. In one on one conversations, there is so much I want to say and most of my friends are patient with me when I type a response, but there are times it takes minutes. I worry about them losing interest while they wait for me as I frantically type. My conversations have fundamentally changed. I find myself saying less, skipping certain parts of what I want to say, and becoming more succinct. I have lots of hot wisdom to drop and I am determined to express myself fully without pressure. I still have a voice, I still have my words, but I have to undo the feeling of resentment of my present state, at the way I present myself to the world that is shaped by forces beyond my control.

Mina: You dedicate the book to yourself, saying, “I love you very much. You deserve everything you desire.” What inspired you to do that?

Alice: I have a gigantic ego and am full of confidence about a lot of things but I am also a puddle of insecurities, loneliness, and self-doubt. Growing up disabled, I was made to feel a lot of shame and marginalized to the point where I questioned whether I belonged in many spaces. I think a lot of people feel that way whether they are disabled or not. It’s easier for me to love others than myself so I just wanted to declare how much I love me and how I want all of my dreams to come true because let me tell you Mina, I have plans to conquer the world, insert evil laugh ha ha ha.

Mina: You write, “Death is an intimate partner of mine.” Tell us about this intimate partnership.

Alice: I turned fifty recently and it was a real head trip. For Time magazine I wrote a piece reflecting on all I have gone through and what my uncertain future holds. Doctors told my parents I wouldn’t live past eighteen so I grew up without any dreams or images of a grown up Alice. I could not see a future for myself so I had to make one on my own. I had to will a pathway into existence. In my memoir Year of the Tiger, I wrote an essay about my first grade teacher Mrs. Shrock. In a note to me several years ago, she remembered one day in class I asked her if I was going to die. And she said no, not now. I had no memory of that but as I am typing this answer I am tearing up thinking about it. Such heavy existential questions and fears preoccupied little six year old Alice’s head. Death has always been a shadowy presence as someone with a progressive neuromuscular disability. I have gone through lots of scary medical moments in my life, most recently this past January when I went to the ER. I was shocked to see so many health care providers without a mask or only wearing a blue surgical one that does not protect from airborne pathogens as effectively as an N95 mask. I’m at high risk for dying from COVID and worked so hard keeping myself safe for four years. It’s exhausting to be sick or disabled and drives me wild that many health care settings do not have mask mandates even though immunocompromised and high risk patients have to go in treatment. We’re still in a pandemic even though our elected leaders would like us to forget that. No one should risk their lives when seeking healthcare. The ER visit resulted in a one day stay in the ICU where I did not receive adequate pain relief during a procedure and my communication device was not allowed in the room. I was powerless, crying nonstop, and unable to tell the nurses and technicians what was wrong. It was terrifying and moments like these where I am vulnerable and treated less than human I wonder if I will die. Not to be a downer for your listeners, but I think about death a lot and it’s a constant in my life, a dance partner that takes me on a few too many dips and twirls for my liking. Death is an intimate partner of mine and it makes me appreciate life. I make the most out of every day celebrating, loving, and caring for my friends, family, and two cats Bert and Ernie. Even though I am in a race against time, I am having as much fun as I can every single day such as this conversation with you. Thanks for having me, Mina.