“An artist is an ordinary person who can take ordinary things and make them special,” said San Francisco artist Ruth Asawa. From her studio in her home in Noe Valley, Asawa created crocheted wire sculptures whose shadows are just as evocative as the art itself. But as the mother of six, Asawa was also passionate about arts education and teaching. As a new retrospective of her work and life opens at SF MOMA, we talk about Asawa’s legacy as an artist, teacher, and community member as part of our Bay Area Legends series.

SF MOMA Ruth Asawa Retrospective Celebrates Her Art and Life as Educator

Guests:

Janet Bishop, Thomas Weisel Family chief curator, SFMOMA; She co-curated the exhibition Ruth Asawa: Retrospective

Terry Kochanski, executive director, SCRAP - a nonprofit education and creative reuse center based in the Bayview and founded in 1976

Andrea Jepson, close friend of Ruth Asawa; Jepson served as the model for the fountain "Andrea" in Ghiradelli Square, and also worked with Asawa on her public school education projects

This content was edited by the Forum production team but was generated with the help of AI.

Retrospective Exhibition at SFMOMA

“Ruth Asawa: Retrospective,” co-curated by SFMOMA’s chief curator Janet Bishop, explores Asawa’s life and career as an artist, advocate and community member. As Bishop notes, Asawa, who raised six children with her husband, artist Paul Lanier, all of whom attended public schools, “invested in San Francisco” through both her art and advocacy. This exhibition, which will travel to New York’s MoMA, the Guggenheim in Bilbao and Switzerland, offers an intimate portrait of Asawa’s life. Highlights include a re-creation of her living room, filled with cherished works by friends and mentors, and a “story booth” where visitors can share their own memories of her impact.

Asawa’s Iconic Wire Sculptures

Ruth Asawa’s iconic crocheted wire sculptures originated from a technique she learned during a trip to Mexico. Using simple materials, she transformed wire into mesmerizing, multi-layered forms that evoke organic shapes and the intricacies of Einstein’s spacetime.

“One thing that [Asawa] said was that ‘an artist is someone who takes ordinary materials and makes them special,’” Bishop says. “I can’t think of anybody who did that better.”

Her Time at Black Mountain College

Ruth Asawa’s artistic vision took shape at the experimental Black Mountain College in North Carolina during the late 1940s. She studied under visionary thinkers like Buckminster Fuller and Josef Albers. “It was a magnet for a whole host of intensely creative individuals,” Bishop says. “The environment was really conducive for her.”

At Black Mountain, Asawa embraced a spirit of relentless creativity and resourcefulness. She once used materials from her student job in the laundry room to make art.

Connection to Nature and Environment

Nature is a constant thread in Asawa’s work, from the patterns she traced on her family’s farm as a child to the botanical drawings that fill her sketchbook. For Asawa, the garden provides “true information,” serving as a rich source of study, particularly for artists.

Though her work draws from the natural world, Asawa is not seeking realism. “She’s not trying to mimic actual trees or branches,” Bishop explains. Instead, Asawa captures nature’s essence—its movement, complexity and quiet order—through abstraction and form.

Advocacy for Arts Education

As a public school parent, Asawa was dismayed at the quality of public art education. “[Asawa] really made it her project to bring arts to public schools,” Bishop says. With grassroots efforts beginning in San Francisco’s Noe Valley, she worked to place practicing artists in public schools.

Asawa had a tremendous respect for children: “Children can learn that they have control over their own space and their own environment — by producing a mural on the wall, they begin to talk about what they’ve done rather than what somebody else has done.”

Her belief in the power of creativity for all students inspired programs that continue to thrive today. “We are Ruth’s legacy,” says Terry Kochanski, executive director of the Scroungers’ Center for Reusable Art Parts (SCRAP), which was founded in 1976. SCRAP began when Asawa realized that teachers did not have sufficient supplies for their students. Today, teachers, students, and the general public can access SCRAP to find all kinds of art supplies from paper, fabric, pencils and more.

Community Impact in San Francisco

Asawa’s bond with the San Francisco community ran deep. A caller named Barry remembers how Asawa welcomed him into her studio and encouraged his artistic pursuits.

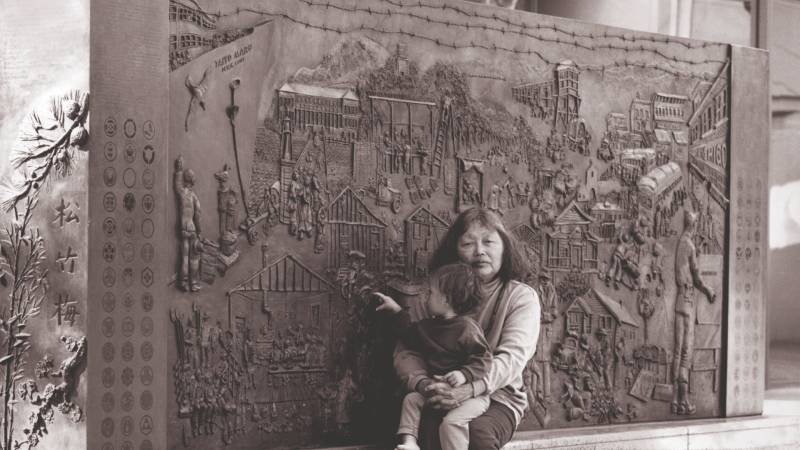

Andrea Jepson, a personal friend and neighbor of Asawa and the model for Asawa’s “Andrea” fountain which is located at Ghirardelli Square, speaks to Asawa’s unwavering commitment to involving local artists and students in public projects. “What Ruth wanted to do was bring artists in to work with the kids.”

Call to Action

Asawa once said that “every minute we’re attached to this Earth, we should be doing something.” Her sculptures, her activism, and her influence on arts education all reflect a life lived fully by that principle.