Listen to the talk:

Inside Dr. Eric Topol's 'Modern Black Bag'

Inside Dr. Eric Topol's 'Modern Black Bag'

In the not-so-distant past, it was the fashion for doctors to carry black bags filled with stethoscopes, blood pressure cuffs and other gadgets.

Eric Topol, a cardiologist and chief academic officer at Scripps Health is one of the few doctors whose black bag isn't gathering dust. But Topol's black bag is no relic of the past: It contains an assortment of the latest wearable devices and gizmos. He describes it as "exponentially more powerful" than an equivalent bag from a century ago.

I met with Topol at a KQED event in San Francisco hosted by Rock Health, an early-stage venture firm that invests in digital health. Topol is a cardiologist and geneticist who has written several books about how technology — and the smartphone, in particular — is changing medicine.

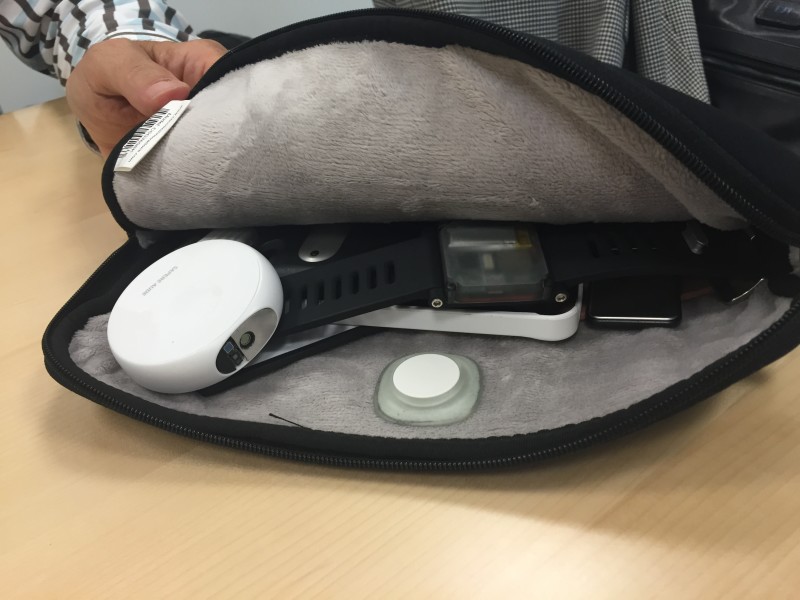

Within minutes, Topol granted me a peek inside his black bag and described its contents: A heart health monitor from AliveCor that attaches to an iPhone; a miniature scanning device called the Scanadu Scout that measures body temperature and blood pressure in a matter of seconds, a coin-shaped sensor that tracks blood sugar levels, and an early-stage prototype of a wristwatch that monitors blood pressure.

Topol is no ordinary doctor. The New York Times described him as a "digital geek" with an "enthusiasm for all things wireless [that] would make any Wired subscriber proud." While many of his physician colleagues are skeptical about all this new medical technology, he is already recommending that his patients use some of the new tools to monitor their vitals between visits. In Topol's view, that's the basis for a new kind of dialogue between doctor and patient: One where you and I can take a far more active role.

Here are some of the highlights from our talk. Note: The conversation was recorded for broadcast and will air on KQED on September 23rd at 8pm PT.

On The Hype and Promise of Digital Health

Five years ago, few people saw potential in digital health. But in 2014, investment in the space topped $4.1 billion as technology entered health care in a big way.

Topol was one of the earliest physicians to publicly praise the new medical technology, and try it out in his own practice. One of the key benefits, he says, is the ability to keep an eye on patients once they've left the hospital. Patients with cardiac issues, for instance, can pickup an Alivecor mobile electrocardiogram, which fits onto a smartphone, and regularly check their heart function for signs of distress.

Throughout our conversation, Topol shared stories of patients who were able to avoid a deadly outcome by using a mobile medical tool. One of his patients came into his office and requested to be fit with a pacemaker. This patient said he had been feeling dizzy with a fluctuating heart rate, which he was monitoring with his Apple Watch. After performing a Google search of these symptoms, the patient guessed that it might be sick sinus syndrome That diagnosis proved to be accurate.

That's all well and good, but it's still early days for mobile health. What are the potential drawbacks of using these tools?

For one thing, not every digital health company takes patient privacy all that seriously. Unlike Apple, many companies make money by selling your data to third parties, including pharmaceutical companies, advertisers and marketers.

Moreover, many of the new systems that store your data are not secure. Topol recently shared a graphic on Twitter showing that a patient in the U.S. is five times more likely to have their medical record hacked than to access it at all. (In July, just a few months after he shared that stat, hackers broke into UCLA and accessed computers with medical records of 4.5 million people.)

One of the limitations of his latest book, "The Patient Will See You Now," is that it doesn't grapple with the issue of whether some patients will misinterpret the data and diagnose themselves with all manner of ills. Topol does concede that mobile health isn't for everyone -- he refers to those who are addicted to Google searching symptoms as "anxious and wired" and "cyber-chondriacs." But he thinks that "most people will do well," and use these tools in moderation.

On Medical Paternalism

Topol has observed that many doctors today maintain the view that patients shouldn't have much of a voice. In the 1960s, many doctors wouldn't tell their patients they had cancer, fearing they would get too distressed. It wasn't until the 1980s that the AMA and other groups included the notion of "informed consent" in their code of ethics.

In 2012, three medical institutions agreed to conduct an experiment called "Open Notes," which involved doctors sharing their notes with patients. According to Topol, some physicians feared that patients would be horrified to see "obese" scrawled in their notes, or they might misinterpret medical jargon like "SOB." But the experiment proved to be a success. Despite these positive results, more recent surveys show that many doctors are still reluctant to share their notes with patients.

On That Time He Gave Stephen Colbert an Ear Exam

Many doctors across the country are still tentative about digital health. But Topol is one of its most avid and earliest supporters. In 2013, he showed off the armory of mobile medical devices in his black bag on the Colbert Show. On live television, he examined Stephen Colbert's heart and performed an ear exam using a mobile otoscope from CellScope.

"The best part was using a handheld device to examine his [Colbert's] heart -- he had to bare his chest on TV. I told Colbert he had an aortic aneurysm to have some fun. Unfortunately, much of that was edited out," Topol said.

On the Reign of the Quitbits

The market is flooded with devices that serve the "worried well," meaning those who are perfectly healthy but are constantly unnerved about getting sick. This set might rush to adopt new devices, such as the Fitbit (which Topol refers to as a "Quitbit"), but they don't use them for long. Topol hopes that Silicon Valley will divert its attention away from building tools for the worried well and instead focus on "devices that are giving clinically relevant information."

But there are barriers to entry for those who are developing true medical devices. These entrepreneurs will need to gain clearance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. This process can take months, and sometimes years.

On His Bad Luck on Flights

"If you see me getting on your flight, reconsider. I seem to have some bad luck in this regard," Topol said. He's only slightly kidding. On three occasions in recent years, he's made an emergency diagnosis in the air. Fortunately, his black bag was on hand.

In one case, he used an Alivecor to make a "very quick diagnosis" that a patient was having a heart attack. The plane made an emergency landing. In his book, 'The Patient Will See You Now,' he recalls another emergency situation where he checked a patient's ECG in the air, as well as performing a cardiac ultrasound and taking their blood pressure -- and concluded that the patient was fine. He writes that in the future, a doctor's intervention wouldn't be required: "All that was needed were the tools to collect the data." This might be taking it a bit far. I would argue that mobile health will improve the doctor-patient relationship, but it isn't going to replace the doctor anytime.