The study’s authors have discussed the case, which occurred about five years ago, at scientific meetings, helping to spread awareness. And the process of manufacturing CAR-Ts has improved over that time, reducing the chance that a cancer cell inadvertently receives the gene meant for immune cells.

“We’re getting much better at getting a purer starting population” of immune cells, said Jos Melenhorst, an immunology expert at the University of Pennsylvania and one of the authors of the report.

The subject of the newly described case was a 20-year-old man with B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. He was participating in a Phase 1 clinical trial for a CAR-T product then called CTL019, which was developed by researchers at Penn and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

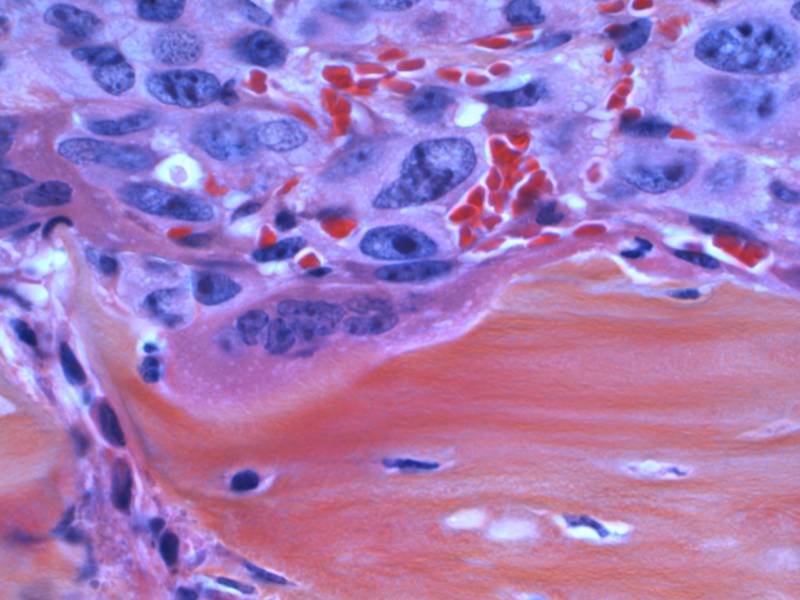

As with any CAR-T patient, the man had immune cells called T cells scooped out from his blood through a process called apheresis. Then, those cells were supercharged with a gene that codes for a receptor (the CAR in CAR-T) that turns the cells into bloodhounds on the scent for a specific marker on cancer cells — in this case, a protein called CD19.

The patient was infused with a phalanx of the killer T cells, which then swarmed and annihilated the cancer cells. Within a month, his cancer seemed to be in complete remission, Melenhorst said.

But as researchers tracked the patient, they noticed something odd. They kept seeing signs of CAR-marked cells, but it wasn’t the body’s T cells expressing CAR anymore.

They ran a battery of experiments and confirmed their suspicions: a leukemic B cell had gotten lumped together with the T cells during the manufacturing process and had also taken up the CAR gene. As a result, the leukemia cell was expressing the CAR, which then attached to the CD19 markers, effectively shielding it from the CD19-sniffing machinery of the boosted T cells. It was as if in a game of musical chairs the targeted seat was already filled by the time the music stopped.

“The CAR-T cell couldn’t bind to the CD19 molecule, and thereby it was essentially hiding in plain sight,” Melenhorst said.

As the T cells attacked the rest of the leukemia cells, this cell laid low for the most part, slowly proliferating into more resistant cancer cells over time. After about nine months, the patient’s cancer — now resistant to CAR-T — had fully returned. He ultimately died from complications from his leukemia.

Melenhorst noted that the case reaches back to the early days of clinical CAR-T use and that improvements in technology since then have allowed manufacturers to ensure that the cells into which they are introducing the CAR gene are less likely to include B cells.

A version of the treatment the patient received was ultimately approved as Novartis’s Kymriah in 2017; the paper published Monday includes some authors from Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research. In a statement, Novartis noted that the manufacturing process used in the case described in the paper was done at Penn and differs from the company’s manufacturing process, which was used in later clinical trials and now for commercial use.

“We are not aware of any cases of this happening in the more than 400 patients treated with CTL019/Kymriah manufactured by Novartis for clinical trials or the commercial setting,” the statement said.

The company said it has checks throughout the process to clear out B cells and that it is following Kymriah patients for 15 years.

“Novartis is continually making improvements to our Kymriah manufacturing process to reduce variability and safely deliver this transformational, personalized treatment to patients in need around the world,” the statement said.

This story was originally published by STAT, an online publication of Boston Globe Media that covers health, medicine, and scientific discovery.