In Transit: Bay Area Transportation News on Everything That Moves

Follow the latest reports and analysis on the past, present and future of transportation in the Bay Area and beyond: rails, roads, bike routes and pedestrian paths, from the Key System to BART and Muni to high-speed rail.

California's 1st Bullet Train Won't Be the One You Probably Expect

If all goes to plan — and when it comes to big infrastructure projects, when does it ever? — a real, live bullet train will begin service in 2028 between Las Vegas and somewhere sort of close to Los Angeles.

A company called Brightline West is building the $12 billion project. The federal government is supporting the 218-mile line with a $3 billion grant announced last year.

That’s the same amount the feds approved for the much better-known and much more slowly progressing California High-Speed Rail project, which could begin carrying passengers on a 171-mile route between Merced and Bakersfield sometime between 2030 and 2033. That’s the first phase of a project voters approved in a 2008 bond issue. The measure envisioned a line connecting San Francisco and Los Angeles that would begin service in 2020.

Brightline West’s project is in the news right now because it held a symbolic groundbreaking Monday for its Las Vegas terminal, located just south of the Strip. Eleven dignitaries, including Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, grabbed mini-sledgehammers to pound in ceremonial spikes on a mockup of a rail line.

“It’s really happening this time,” Buttigieg says.

One key difference between Brightline West’s project and California High Speed Rail’s slow-moving efforts in the Central Valley is that much of Brightline’s route will run down the center median of Interstate 15.

That choice dramatically simplifies acquiring property for the project, in contrast with CAHSR, which has spent years purchasing the roughly 2,300 individual properties it needs to complete the Merced-Bakersfield line. As of last December, it still needed to buy 37 parcels to complete its acquisitions for that phase of the project.

Brightline West’s southern terminus will be in the San Bernardino County town of Rancho Cucamonga, about 40 miles from Los Angeles. Passengers could connect there via Metrolink trains for the 80-minute ride to Union Station in downtown L.A.

Brightline plans one intermediate stop, in Victorville, and says its trains will make the trip between Las Vegas and the L.A. exurbs in a little more than two hours. The southbound trip from Las Vegas can be more than twice as long, especially on weekends.

The company projects 11 million one-way passengers per year. Company founder and chairman Wes Edens says round-trip ticket prices will be about $400 — equivalent to round-trip airfare — but could fluctuate with seasonal demand.

A Transportation Tax Measure Is Taking Shape for 2026 Ballot. Advocates Want to Make Sure It's Used for Transit, Not Freeways

Transit advocates have generally gotten behind a bill unveiled earlier this week that would authorize a 2026 vote on a tax measure to support Bay Area transit and other transportation needs.

But a progressive transportation group declined to participate in the bill announcement in San Francisco to express concern that money raised by the proposed tax could be used to widen highways.

Oakland-based TransForm said after SB 1031 was announced Monday that using revenue from the proposed tax to enhance highways — including by building new toll lanes — would encourage more driving in the future and thus perpetuate the environmental damage wrought by motor-vehicle traffic.

Zack Deutsch-Gross, TransForm’s policy director, said in an interview that the planned measure, which has been under development for years and is the subject of continuing negotiations, needs to focus on major improvements in the Bay Area’s fractured transit network and on making existing streets and roads safer for all users.

“We need to be laser-focused on what aspects of the measure will truly meet our transportation goals, advance economic prosperity in the region, as well as climate and equity. The reality is that highway expansion is not one of those goals and undermines all of them,” Deutsch-Gross said.

SB 1031, introduced by Democratic state Sens. Scott Wiener of San Francisco and Aisha Wahab of Hayward, would guarantee at least $750 million a year to help deficit-plagued Bay Area transit agencies pay for day-to-day operations.

That funding would also go to improve coordination among the region’s 27 transit operators, possibly helping subsidize initiatives like flat-rate monthly and weekly passes and eliminating payments when transferring from one agency’s buses to another’s trains.

But the bill is just one of many steps in the process of drafting the ballot measure and doesn’t include key details about what exactly Bay Area voters will eventually be asked to approve. Those details include:

- How much money will the measure try to raise? Early last year, the effort appeared to aim for $1 billion a year in revenue. Transit activists, citing the scale of operators’ needs and the cost of creating a regional network, have called for a levy of $2 billion a year.

- What kind of tax will voters be asked to approve? The possibilities include a sales tax, a parcel tax on property owners or a payroll tax to be borne by employers. Another source could be a regional vehicle-registration surcharge, which would be imposed after 2030, likely as part of a separate ballot measure. SB 1031 does not include the option of a regional income tax on high-income earners, an idea promoted by Seamless Bay Area, a group working to better coordinate the region’s transit services.

- Beyond transit, what kinds of investments might the tax revenue might be used for?

- Will the tax measure come from the Metropolitan Transportation Commission and require a two-thirds vote to pass? Or will it be a citizen’s referendum that potentially might require just a bare majority to succeed?

On the question of how money will be spent, there’s general agreement that repairing existing roads in the region and projects that improve safety for people walking and biking will be eligible.

But, as indicated by TransForm’s stance on SB 1031, there’s a debate on how much, if any, revenue should go to support projects like toll lanes, interchange improvements or ambitious projects like rebuilding the North Bay’s Highway 37 in response to congestion and rising sea levels.

During an MTC discussion of the proposed tax measure in January, commission vice chair Nick Josefowitz argued spending on highway expansions should be ruled out.

“I think we just need to draw a line in the sand and say, ‘For this measure, we are not going to be funding projects that make climate change worse. We’re not going to be funding highway-widening projects,'” Josefowitz said.

That drew a heated response from Jim Spering, who represents Solano County on the commission. He said the measure should also respond to drivers’ needs.

“I find it amusing, all these groups saying no highway expansion — you know, the same ones who are advocating for equity and fairness, you know, ‘Help our disadvantaged, low-income communities,'” Spering said. “And (they) just blatantly say, ‘No highway expansions’? Many of the highway expansions are helping those very people.”

Spering and others on the commission have suggested that meaningful road improvements will be necessary to get the maximum possible buy-in from voters around the region. A series of polls on a transportation tax have shown such a measure falling well short of two-thirds support. The

TransForm’s Deutsch-Gross said he believes a measure focusing on transit, road repairs and enhancing transportation options like cycling and walking can win without including freeway projects.

“I feel very confident that voters from the South Bay to the North Bay will deeply care about transportation investments like safer streets, like repairing roads and potholes, like active transportation investment and public transit,” he said. “I think there’s something for everyone in this measure without highway expansion.”

Transportation Poll: Voters Want a 'Seamless' Transit Network. Also, Safer Trains and Buses. And Investment in Roads

The latest in a series of polls trying to gauge voter willingness to pass a major regional transportation tax measure in 2026 suggests widespread enthusiasm for a wide array of transit improvements — but shows overall support falling well below the threshold needed for approval.

The poll was sponsored by Seamless Bay Area, a group that has been working since 2018 to transform the region’s hodgepodge of 27 transit agencies into an integrated, rider-friendly network. It was funded in part by the Beneficial State Foundation, a group that advocates for racial and economic justice. Seamless Bay Area has been at the forefront of groups promoting a future tax measure that could raise as much as $2 billion a year.

The survey of 600 likely voters (PDF) from all nine Bay Area counties asked respondents whether they’d support a 1% regional income tax on individuals earning more than $300,000 a year and households earning over $500,000 annually.

The answer: 57% said they were inclined to vote yes.

That’s 10 percentage points short of the two-thirds majority the measure would need to pass and roughly in line with a series of polls over the last year or so that show anywhere from 51% to 63% support for a big transportation revenue measure.

That 51% figure was recorded last October when a poll conducted for the Metropolitan Transportation Commission asked likely voters about support for a smaller income tax — one-sixth of 1% — but with no income limits on who would pay. The 63% level came a year ago when the MTC pollster asked voters about support for a 1/2-cent regional sales tax increase to support transportation.

Ian Griffiths, Seamless Bay Area’s policy director, said the new poll results show “a strong base of support. Well over a majority of Bay Area voters support the idea of a ballot measure.”

Griffiths noted that the poll found overwhelming support for initiatives like coordinating schedules among all local transit operators and integrating and simplifying fares — steps that are crucial to creating a seamless regional public transportation network. He said improving the performance of existing services scored higher in the poll than measures like simply offering more buses, trains and ferries.

“The improvements that we asked about focused more on increasing service and providing faster, more frequent service and a network of lines that come every 10 minutes,” Griffiths said. “That was very popular, but not nearly as popular as coordination of the existing system. … There’s a very strong consciousness among the public of the poor level of coordination right now and the inconvenience of the existing system.”

The poll also found strong support for repairing the region’s roads and freeways and beefing up public safety measures on buses and trains by adding more security personnel, cameras and lighting. Respondents also said they want to see annual audits of how the tax revenue will be spent and to have online access to detailed accounting of agency spending.

Although advocates of the 2026 measure have been pointing to the dire state of public transit finances as the principal argument for a new tax, the Seamless poll ranked that as the least persuasive argument for the proposal.

Griffiths said that while that argument was “reasonably effective” in convincing the Legislature to come up with an emergency aid package for transit last year, it “is not especially effective at convincing the public in the context of a potential tax increase. People are not excited about the idea of paying more for the same as what they used to have before the pandemic.“

Under a provision of the transit aid package the Legislature passed last year, operators will be required to show they’re making progress in responding to persistent complaints related to issues like public safety and cleanliness.

The aid package makes the Metropolitan Transportation Commission responsible for monitoring compliance with benchmarks that vary from agency to agency. BART, for instance, has promised to install new, hard-to-evade fare gates at all 50 of its stations by the end of next year — a key piece of the agency’s “Safe and Clean Plan” to win back riders in the wake of the pandemic. If BART fails to deliver the fare-gate project on time, the MTC could, in theory, withhold some of the state emergency funds BART is in line for.

Griffiths says another finding in Seamless Bay Area’s poll — that a majority of voters don’t trust the government to spend transportation funds efficiently — highlights the need for transit agencies to deliver on their promises. He argues that visible progress in making transit easier to use will draw people back on board.

“As soon as people are riding more, this poll indicates they’re more likely to support the measure,” he said. “So, I absolutely think we have the opportunity in the next two years to build on that 57% support and get closer, to get it higher. And that’s going to depend upon us delivering on a lot of these promises that we’ve been talking about for years and years and years. And fortunately, there’s finally some progress underway.”

As Waymo Expands, One Lawmaker Pushes to Give Locals More Control

A South Bay lawmaker said the state’s decision to allow Waymo to expand its autonomous taxi service over the protests of local officials shows the need to give cities and counties more say in future approvals.

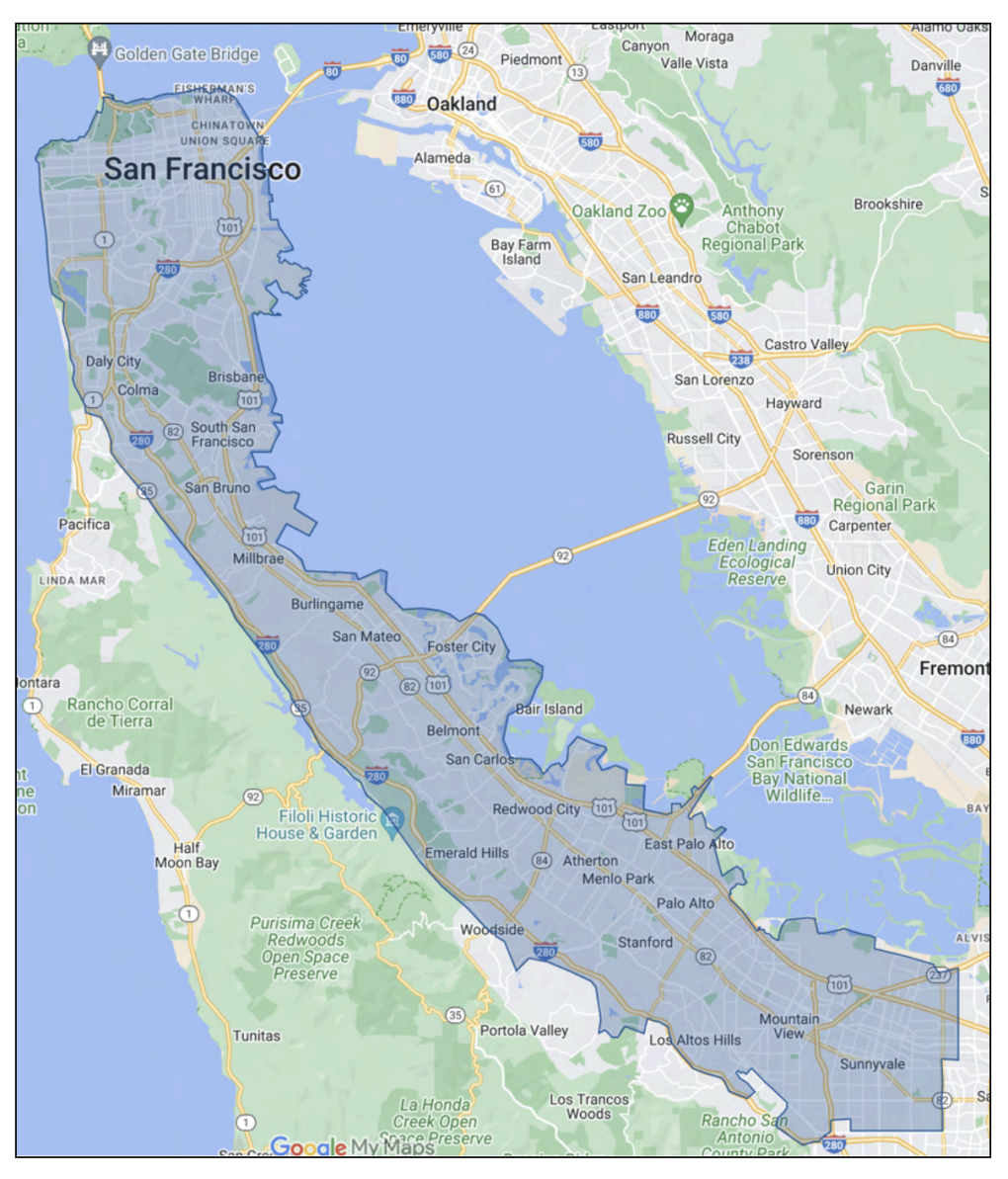

The California Public Utilities Commission announced Friday it had given Waymo the go-ahead to expand paid operations immediately on the Peninsula and across much of Los Angeles County. Until now, the company’s service was limited to San Francisco.

The decision from the commission’s Consumer Protection and Enforcement Division came after officials in Los Angeles, San Francisco and San Mateo County had filed objections to Waymo’s enlarged service area.

Among other concerns, the official protests argued that Waymo was seeking fast-track approval without allowing cities and counties to weigh in on the process and without being required to disclose detailed safety data to local governments.

The Los Angeles Department of Transportation urged the commission to hold off on approving Waymo’s expansion until the Legislature acts on a bill from state Sen. Dave Cortese (D-San Jose).

Cortese’s SB 915 would give city and county governments the power to grant or deny local operating permits to autonomous vehicle services after they’ve secured approvals from the Department of Motor Vehicles and the CPUC.

In an interview Friday, Cortese said the CPUC’s rapid approval of Waymo’s expansion “punctuates the need for a much better and more comprehensive and more thorough system of oversight and enforcement and control of the motor vehicles that are going to be on the street as (autonomous vehicle technology) continues to advance. “

Cortese said local control over autonomous vehicle services is an extension of local governments’ authority over how public streets are managed.

“There’s always been the ability for local governments to establish and control and enforce motor vehicles on their streets, whether it’s through speed limits, whether it’s establishing bike lanes, safe pedestrian crossings, safe routes to schools — those are all local jurisdictional matters,” Cortese said. “And right now, these autonomous vehicles are exempt from that, primarily because they weren’t contemplated when California law was established around motor vehicles.”

Cortese said his bill would also push autonomous vehicle operators — besides Waymo, more than three dozen have received DMV approval for some level of testing in the state — to cooperate more fully with the communities they want to operate in. He argues that the process of gaining local approvals will be no more burdensome than it is for any other kind of business.

“I see no reason why politically they can’t deal with cities and counties as pretty much everybody else who needs a permit does in this world,” Cortese said. “Whether it’s eBay trying to build a new campus or Apple trying to build a new campus or a guy trying to open up an ice cream shop on the corner. Everybody, every franchise. You know, it’s worked for everybody else. It’s worked for McDonald’s.”

Waymo said in a statement issued after the CPUC’s approval it welcomed the commission’s “vote of confidence in our operations.”

In Transit Weekly Reader: Feb. 26–March 1

San Francisco Chronicle: Police chases are killing more and more Americans. With lax rules, it’s no accident. An investigation by Chronicle reporters found “at least 3,336 people were killed as a result of police pursuits throughout the U.S. from 2017 through 2022. At least 15 of them were officers. More than 52,600 people were injured from 2017 through 2021, according to government estimates.”

San Francisco Standard: Fewer chases, but more crashes. SFPD collision rates are highest among California’s big cities. “The Standard found that 41%—or 47 of the 115 pursuits initiated by the San Francisco Police Department in a four-year period—resulted in a collision. That was nearly twice the statewide average of 22% of pursuits resulting in collisions, and significantly higher than the collision rate for neighboring police departments in Oakland (26%) and San Jose (33%).”

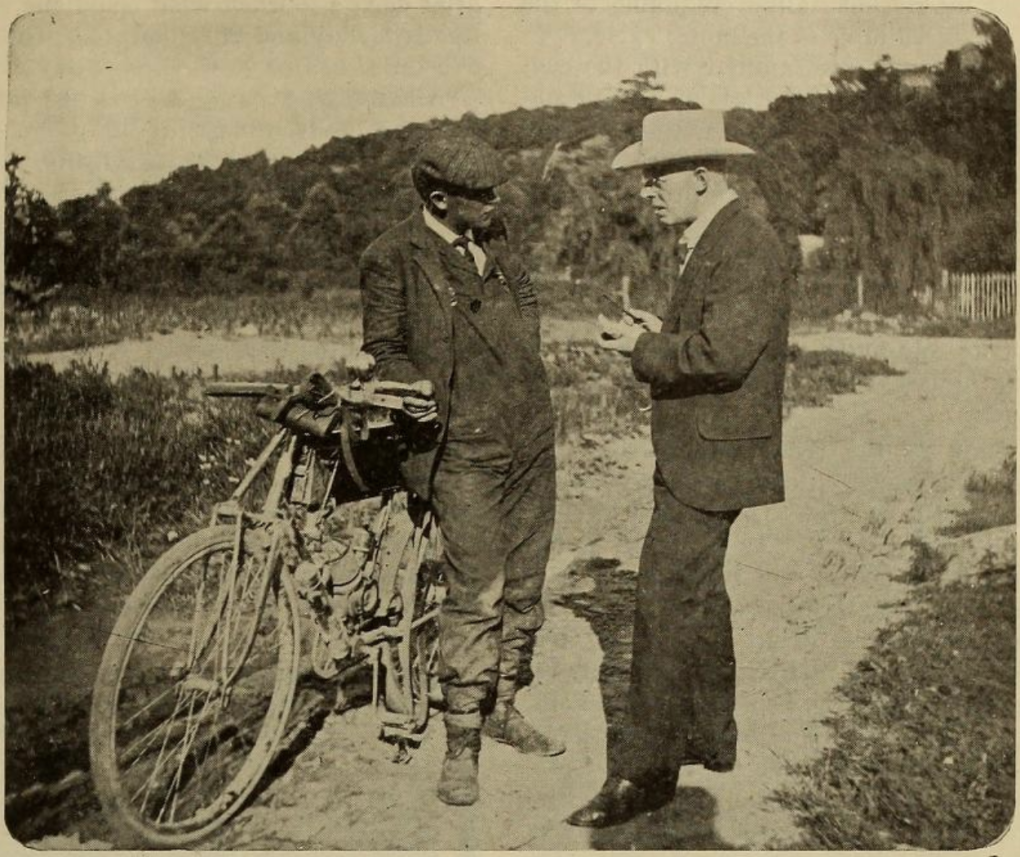

KQED: Remembering the East Bay native who made ‘the first motorized trip’ across the United States. Chances are you’ve never heard of George Adams Wyman. In May 1903, he and his gasoline-powered bicycle set out from Lotta’s Fountain on Market Street in San Francisco on a 3,800-mile journey that earned him a brief moment of fame.

Bay Area News Group: Drivers who survived San Jose hijackings honored for courage. “District Attorney’s Office recognizes VTA bus driver who kept machete-wielding man at bay and UPS driver who famously thwarted gun-toting couple.”

Oaklandside: Oakland has fallen way behind schedule in paving roads. “In 2021, the Oakland City Council passed a $300 million, five-year plan to fix about 400 miles of roads between 2022 and 2027. Only 36 miles from that plan have been paved. The city is behind schedule because of a ‘slowdown in contract processing as well as some equipment challenges impacting in-house crews,’ according to the city’s Department of Transportation.”

San Francisco Examiner: SFMTA credits a series of improvements for increased ridership. The city’s transportation agency says Muni ridership “rose 25% in 2023 to its highest level since the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020, which officials credited to improved ridership experiences on buses and subways while adapting to new travel patterns.”

Los Angeles Times: New high-speed train from Vegas to SoCal will be a model for the nation — if it succeeds. “When Simon Akinwolere, a 27-year-old cruise director, needed to commute from Orlando to Miami, he sorted through his travel options. He could drive the 235 miles, spending four hours dealing with traffic. Flying would be faster, but he’d endure security lines and baggage hassles. He settled on a new option: Buy a train ticket that promised a 3½-hour ride, access to a conference room and a free buffet with self-serve beer and wine taps.”

Vox: Driving at ridiculous speeds should be physically impossible. “Speeding plays a role in over 12,000 US car fatalities per year, around a third of the national total. But an emergent technology could dramatically reduce that death toll, if not eliminate it entirely.”

Gothamist: The lasting toll of violence on New York’s subway. “… Gun violence on mass transit exacts a lasting toll that can’t be fully captured in statistics. Just ask Fitim Gjeloshi, who helped save dozens of passengers on a northbound Brooklyn N train on April 12, 2022, when Frank James set off a smoke bomb and fired 32 shots from his Glock 17 during morning rush hour.”

Stateline: No fare! Free bus rides raise questions of fairness and viability. Just 23 cities nationwide had ridership in 2023 equal to or higher than in 2019, and 14 of those had free rides at least part of the year, according to the Stateline analysis of federal data.

The East Bay Native Who Made the First Motorized Trip Across America

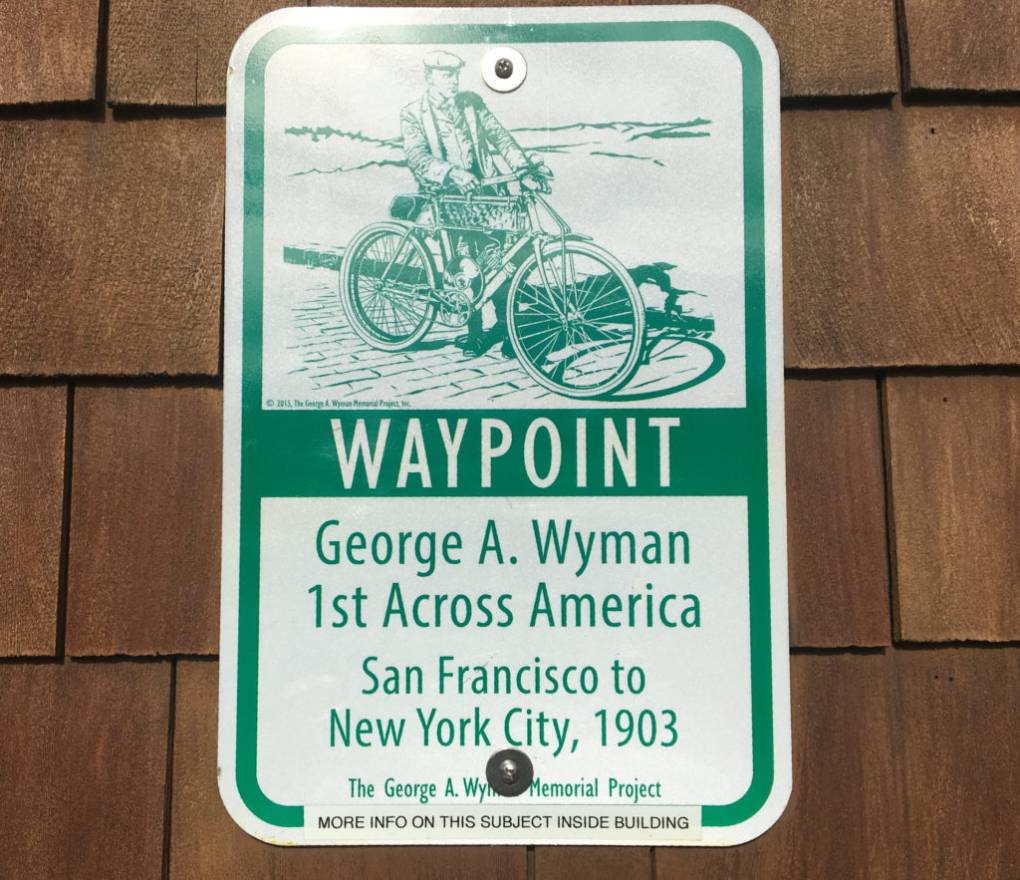

Near the beginning of a trip to the Great Plains in August 2017 to see that summer’s total solar eclipse, my traveling companion and I pulled off Interstate 80 in the Sierra at a spot called Nyack. There’s a gas station and convenience store there, and on the wall of the latter was a sign that got my attention: “Waypoint: George A. Wyman, First Across America.”

I snapped a picture and then forgot about it. Stumbling across the image several years later, I looked up George A. Wyman and what the whole “1st Across America” thing is about.

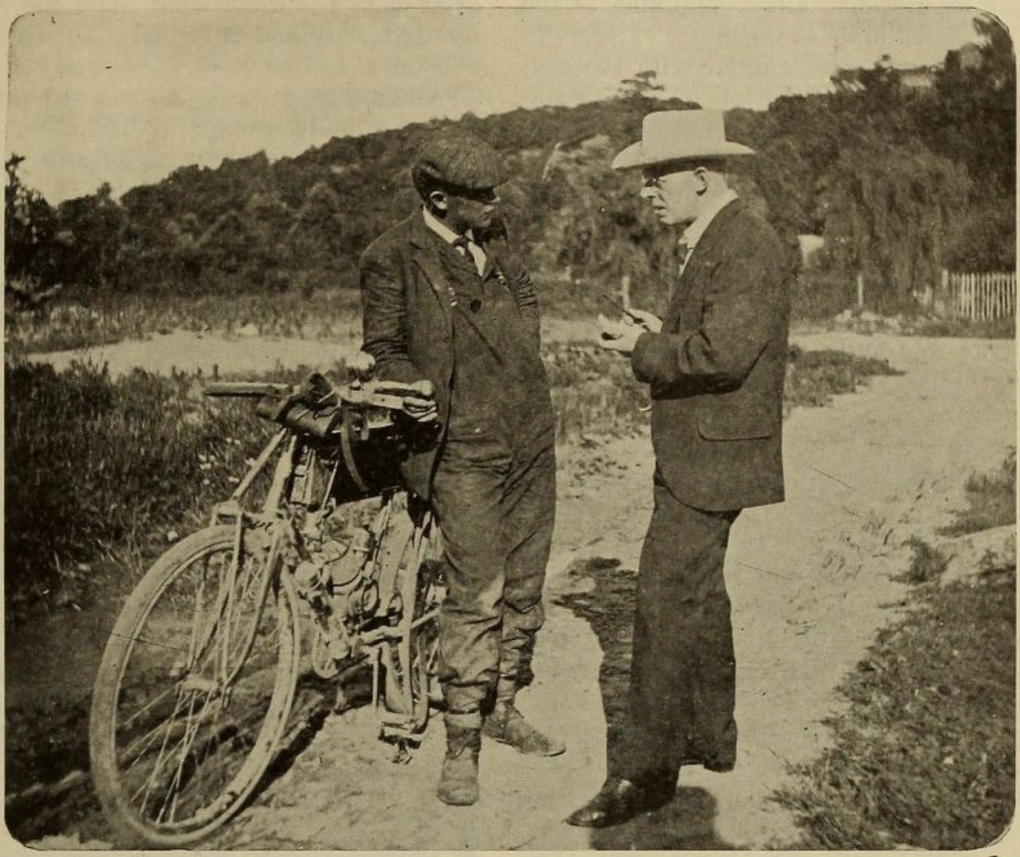

In short, Wyman was a Hayward native, born in 1877, who at the age of 26 made what is said to have been the first trip across the United States via motorized vehicle — in his case, a motorized bicycle produced by a company in San Francisco.

Wyman’s journey began May 16, 1903, at Lotta’s Fountain, on the little triangle where Kearney and Geary streets meet Market. That’s a spot that became famous as a meeting place for survivors of the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake, a bit of history commemorated with a pre-dawn ceremony every April 18, the quake anniversary.

Naturally, having heard this much, you’ll want to read more about George A. Wyman and his machine.

If I’m right about that, you’ll want to check out the George A. Wyman Memorial Project, which has published the adventurer’s own day-by-day account of his cross-country journey. The site includes a pretty good tale, too, about how the late publisher of the Los Angeles Times found and restored a 1902 vintage motor bicycle that he believed to be the one Wyman rode.

The daily journal of the trip is drawn from Wyman’s dispatches to a long-extinct publication called Motorcycle Magazine, which sponsored the trip. The story that unfolds in those reports shows Wyman to have been unflinching in the face of both frequently hostile conditions along his route and the repeated breakdowns of his 90-pound, 1.25-horsepower machine.

This was no modern road trip because, in many places, highways were non-existent. Wyman wrote that he often preferred the bone-rattling ride along railroad ties to struggling through the deep sand or intractable mud along what passed for roads. When the trip was over, he estimated he’d ridden 1,500 miles on the cross-ties; on several occasions, he had close calls with trains that overtook him when he was on the tracks.

Mostly, Wyman was good-humored and matter-of-fact about most of his difficulties. Here he is in June 1903, somewhere in western Nebraska, remarking on a broken piece of equipment:

“One more cyclometer was sacrificed on the ride from Ogallala to Maxwell (Nebraska), snapped off when I had a fall on the road. I do not mention falls, as a rule, as it would make the story one long monotony of falling off and getting on again. Ruts, sand, sticks, stones and mud all threw me dozens of times. Somewhere in Emerson I remember a passage about the strenuous soul who is indomitable and ‘the more falls he gets moves faster on.’ I would like to see me try that across the Rockies. I didn’t move faster after my falls. The stones out that way are hard.”

For me, Wyman’s story is most compelling as a snapshot of the time just before the kind of cross-country trip he was attempting would be commonplace. While Americans had always been fascinated with the idea of picking up and traveling long distances — that’s how California and the rest of the United States happened, after all — taking a cross-country trip just to do it was an experience reserved for the well-to-do and usually happened on rail. Wyman was riding into a future in which all the terrible roads would be improved, and inexpensive vehicles and gasoline would transform both the travel experience and expectations about what that experience would (and should) be. The ability to take a trip like the one I and millions of others made in 2017 to see a celestial spectacle has long since been taken for granted.

Wyman frequently commented on the reception he got along the way. When he limped into Cheyenne, Wyoming, after a day battling rain and mud so deep and thick that he had to get help from a friendly rancher to pull his motorbike free, he was met with suspicion from one innkeeper after another. Wyman eventually figured out why.

“With my coat torn in several places and one sleeve of it hanging by a thread, my leggings hanging in shreds, no waistcoat on, dripping wet and splashed with mud all over,” he didn’t present the picture of a guest any hotel would welcome.

“‘All full’ was the word I got at the first hotel, and at the next it was the same,” he wrote. “After I had tried three and been refused, I was satisfied that it was my appearance that was the reason. To make the matter worse, I discovered that my big ‘.38’ revolver had worn a hole in my pocket and was sticking through so that it showed plainly between the torn part of my coat. I must have looked like a ‘bad man’ from the wilds.”

Finally realizing the impression he was making, he took pains to explain that he was on a cross-country trip. “I finally found a woman who kept furnished rooms, who eyed me suspiciously and said she had no room, but would fix me up a cot,” he said. “She listened to my story and finally fixed me up a nice room, and I stayed there two nights.”

Elsewhere, he encountered amazement at both the length of his journey and the technology he was using. On June 24, he stopped for the night in Ligonier, Indiana, a town about halfway between Chicago and Toledo, Ohio:

“I thought that when I got east of Chicago folks would know what a motor bicycle is, but it was not so. In every place through which I passed, I left behind a gaping lot of natives, who ran out into the street to stare after me. When I reached Ligonier I rode through the main street, and by mistake went past the hotel where I wanted to stop. When I turned and rode back the streets looked as though there was a circus in town. All the shopkeepers were out on the sidewalks to see the motor bicycle, and small boys were as thick as flies in a country restaurant. When I dismounted in front of the hotel the crowd became so big and the curiosity so great that I deemed it best to take the bicycle inside. The boys manifested a desire to pull it apart to see how it was made.“

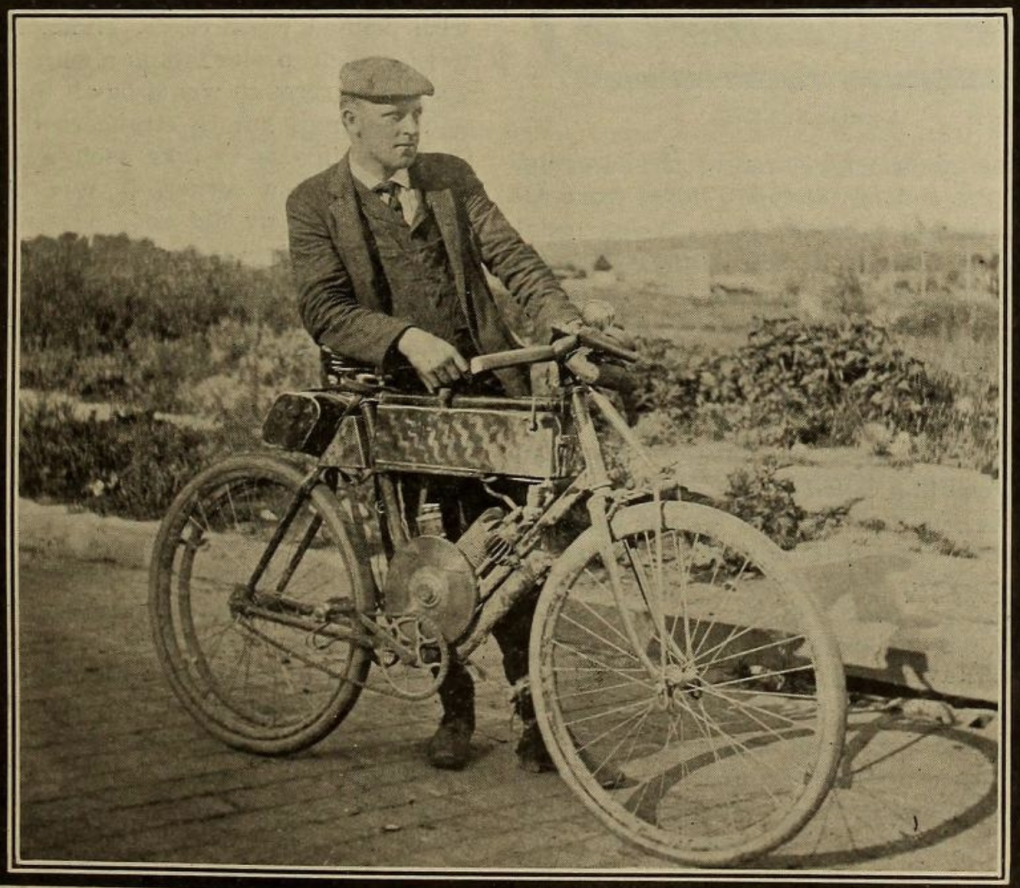

Wyman’s motor bicycle was a sort of hybrid, consisting of what looked like a conventional bicycle frame fitted with a small gas tank and motor. A leather drive belt — which broke and required mending constantly — ran between the motor’s crank shaft and a pulley on the rear wheel. The motor and transmission apparatus finally quit for good as Wyman neared the end of his journey in New York City. Luckily, he could simply pedal the bike, and pedal he did, riding the last 150 miles from Albany to New York City without stopping overnight to sleep:

“I made frequent stops to rest and I attracted more than a little attention but I was too tired to care. I can smile now as I recall the sight I was with my overalls on, my face and hands black as a mulatto’s, my coat torn and dirty, a big piece of wood tied on with rope where my handlebars should be, and the belt hanging loose from the crankshaft. I was told that I was ‘picturesque’ by a country reporter named ‘Josh,’ who captured me for an interview a little way up the Hudson, and who kept me talking while the photographer worked his camera, but to my ideal, I was too dirty to be picturesque. At any rate, I was too tired then to care. All I wanted was a hot bath and a bed.”

Wyman’s arrival in New York after his 50-day epic attracted little attention. A few papers across the country carried a brief Associated Press story that hailed him as “the first man to cross the American continent on a power-propelled road vehicle.” Motorcycle Magazine suggested one reason the feat may not have gained wider attention: Wyman himself didn’t boast about it.

“Now that the narrative has been completed and a review of the whole trip can be taken, it stands out in its entirety as a supreme triumph for the motor bicycle,” the magazine said in November 1903. “It was not only the most notable long distance record by a motorcycle, but also it was the greatest long trip made in this country by any sort of a motor vehicle. This is a fact to which attention was not called by Wyman in his story and it is one that should be emphasized. In fact, Wyman’s story was altogether too modest throughout.”

In Transit Weekly Reader: Feb. 19–25, 2024

•KQED Bay Curious: Is the SMART Train Easing Highway 101 Traffic in Marin and Sonoma? The North Bay’s rail agency has come a long way since launching in 2017. And it’s the only public transportation system in the entire nine-county Bay Area that carries more passengers than before the Death Star, aka COVID-19, zapped transit services everywhere. But a Bay Curious listener wants to know whether SMART is making a dent in traffic congestion along U.S. 101.

•KQED In Transit: BART Workers Demand Improved Security After Robbery Outside Agency HQ. Members of Amalgamated Transit Union Local 1555 appeared at this week’s BART board meeting in what amounted to a protest of a Feb. 14 incident in which an employee was robbed at gunpoint just outside agency headquarters.

•San Francisco Examiner: BART Survey Says Rider Satisfaction Highest in a Decade

•San Francisco Chronicle: Robotaxis Are Causing Less Mayhem on SF Streets. City Officials Explain Why

•San Francisco Standard: Hornblower’s SOS Call: Sunk by the Pandemic, Alcatraz Cruise Operator Files for Bankruptcy

•Los Angeles Times: Driver Found Guilty of Murder in Collision That Killed Two Young Brothers

BART Workers Demand Improved Security After Robbery Outside Agency HQ

In the aftermath of an early-morning armed robbery of a BART employee outside the agency’s downtown Oakland headquarters, one of the agency’s unions is demanding swift action to improve security for workers.

The robbery at 3 a.m. on Feb. 14 was disclosed during the agency’s board of directors meeting on Thursday.

“This was an armed robbery, several people with guns chasing our employee up and down the street as he struggled to get into the building for safety,” said Jesse Hunt, president of Amalgamated Transit Union Local 1555, which represents BART’s train operators, station agents and other operations employees.

Hunt and several Local 1555 members appeared at the meeting to call on the agency to address safety concerns.

Hunt said workers face “challenges that compromise their safety on a daily basis, from verbal abuse, being spit on, physical assaults and having their personal vehicles broken into. … It is unacceptable to continue to hear about the incidents of assaults and armed robberies our members endure while simply reporting to their jobs and working in the field to service the public.”

Rachel Miranda, a senior operations foreworker, told the board that employees have been dealing with crime in the area around the agency’s headquarters at 21st and Webster streets for more than two years.

Miranda said that when her coworker “was strong-armed, with multiple guns pointed at him in front of the building, and feared for his life, we, the frontline workers, say that’s enough. No one should be afraid to come into work.”

The board also heard a plea from another senior operations foreworker, Olivia Spicer, who said staff at headquarters were shaken by news of the robbery and security camera video of the incident.

“Please, please help us,” Spicer said, near tears. “Please. Because I still want to come here. I still want to work here. I still love working for BART.”

BART executives at the meeting acknowledged what they described as “challenges” in the headquarters area, including the safety of employees walking to and from parking lots in the neighborhood late at night and early in the morning.

Michael Jones, BART’s deputy general manager, said the agency has increased the police presence around the headquarters building. A BART officer has been stationed there during the overnight hours and officers are making drive-by patrols around the clock.

Jones said the district is also working to start a shuttle service to take workers to and from parking lots near the Paramount Theatre and the Kaiser Center.

“It’s unfortunate we have to do that, but traversing from here to the Paramount Theatre at 3 o’clock in the morning to park or from here to 19th Street late at night or early in the morning has become challenging,” Jones said.

“We’re just trying to make sure that we can do what we can right now to make sure that our employees know that we value their safety, and we’re going to do what we can do to keep them safe,” he said.

But Local 1555’s Hunt made it clear that he and his members are looking for what he called “decisive action” to improve worker safety.

He outlined several steps he wants the agency to take, including:

- Increased security presence throughout the BART system, including collaboration with local law enforcement agencies in the five counties the agency serves.

- Training programs to help frontline employees handle safety threats.

- Improved communication with employees about security concerns so that frontline employees know what to expect when they report to locations throughout the BART system.

- Analysis of incidents to determine how to make employees and patrons safer.

- Scheduling changes that would allow employees to come to work more rested and alert to deal with “the challenges that they face every day.”

“We need the BART board to end what appears to our members to be simply lip service intended to minimize BART’s liability when it comes to safety instead of actually making us safer,” Hunt said.

At the request of BART board president Bevan Dufty, agency management will make a formal presentation on employee safety at the board’s next meeting on March 14.

New Bill Would Ban Tolls for People Walking and Biking Across California Bridges

Back in 2014, the Golden Gate Bridge district was looking for ways to close its perennial budget deficit and considering a long list of measures to help close the fiscal gap.

One idea on the list was imposing a toll on people who came to the bridge to walk or ride their bikes across it. The proposal wasn’t popular, and Assemblymember Phil Ting of San Francisco headed it off with a bill that prohibited bridge tolls on pedestrians.

The bill, passed and signed into law by Gov. Jerry Brown in 2015, expired in 2021.

Fast forward to this week. The bridge district, facing a five-year deficit estimated at $220 million, opened its formal public presentation of a proposal to raise tolls for motor vehicles. The fee would rise between 35 and 50 cents a year for the next five years. Fastrak users would pay between $10.50 and $11.25 by the fifth year of increases in 2028. Those who use other payment methods would be charged more.

This time around, the bridge district is not discussing charging people to walk or ride bikes across the bridge.

But Ting and his allies in the cycling and pedestrian community want to make sure that option is taken off the table for good.

Using the Golden Gate Bridge as a backdrop Thursday, Ting announced AB 2669, a bill that will permanently ban tolls on people walking, biking or scootering across any bridge in the state.

“At a time when we’re dealing with climate change, and we’re trying to encourage more people to walk, more people to bike, I can’t think of a greater disincentive than actually charging a toll for pedestrians and cyclists to cross one of the most famous bridges in our world,” Ting said at a Crissy Field press conference.

“These are modes of transportation that every level of government should be encouraging and incentivizing everyone to use,” said Christopher White, interim executive director of the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition. “But the norm is that driving and cars are subsidized while using sustainable active modes suffers from lack of investment. This bill flips that script.”

For Karen Rhodes, the president of the board of directors of Walk SF, maintaining spaces accessible to everyone is an equity issue.

“People in community, outdoors with each other, young, old, local, visitors from all over the world — tens of thousands of people making use of our bridges in this way every day,” Rhodes said. “We’re all walking, rolling, using mobility aids to get outside and enjoy the restorative benefits of being outdoors.”

Ting said that the worst thing the state can do is to penalize active modes of transportation. He said that there is an active coalition of support for his proposition all over the state.

The bill will get its first hearing in March.

And a historical note: For the first 33 and a half years after the bridge opened in May 1937, the bridge actually did charge pedestrians to stroll across the span. The initial charge was a nickel — deposited in a turnstile — and was raised to a dime in 1938.

The reported rationale for levying a pedestrian fee was that the district was legally obligated to charge all bridge users while it was paying off the voter-approved bonds that paid for the bridge’s construction.

The bridge district repealed the pedestrian toll in 1970, which was also the year cyclists were first allowed to use the bridge.

From the vantage point of 2023, the fee doesn’t look like it was a big moneymaker. In November 1970, the district reported it had collected $132 from pedestrians and $58 from cyclists.

The Golden Gate Bridge Still Has a Great View. Soon You'll Pay a Bit More to See It

Here are two things that anyone who crosses the Golden Gate Bridge can count on: You’ll get a close-up view of one of the most iconic structures anywhere on the planet, and pretty soon, you’ll pay more to do it.

The Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District, the agency that owns and operates the span and the associated ferry and bus systems, will this week take the next step in a process that, if history is any guide, will raise bridge tolls for the next five years. The goal is to help close the total estimated deficit over that time frame of $220 million.

The cost for most passenger vehicles to cross the span now ranges from $8.75 if you use FasTrak to $9.75 for those who pay by invoice.

The bridge district is considering five different toll scenarios that would raise tolls anywhere from 35 to 50 cents per year for the next five years. Under the most expensive scenario, which would raise about $139 million, FasTrak tolls would rise to $9.25 on July 1 and reach $11.25 on July 1, 2028. The charge for drivers paying by invoice would rise to $10.25 in July and hit $12.25 in 2028.

The smallest increase the district has floated would raise the FasTrak toll to $10.50 by 2028. Tolls-by-invoice would go up to $11.50. The agency would raise about $101 million in new revenue under that scenario.

The bridge district is holding a series of public outreach sessions on the proposed tolls. Those will include two one-hour Zoom webinars — on Wednesday, Feb. 14, at noon and Thursday, Feb. 15, at 7 p.m. — and a formal public hearing on Thursday, Feb. 22.

You can also submit a public comment by email at publiccomment@goldengate.org or via an online comment form.

The district’s board of directors is expected to make a final decision on the toll proposal next month.

On the eve of another Golden Gate Bridge toll increase some time ago, I was moved to delve a little into the district’s toll history. Here’s a slightly updated version of what I found:

“If you take the really long view, even the pricey-looking tolls now being proposed look like a bargain.

“Today, only southbound drivers pay a toll. In 1937, the year the bridge opened, drivers paid 50 cents to cross — each way. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics CPI Inflation Calculator, that $1 round-trip charge is the equivalent of $21.42 in 2024 dollars.

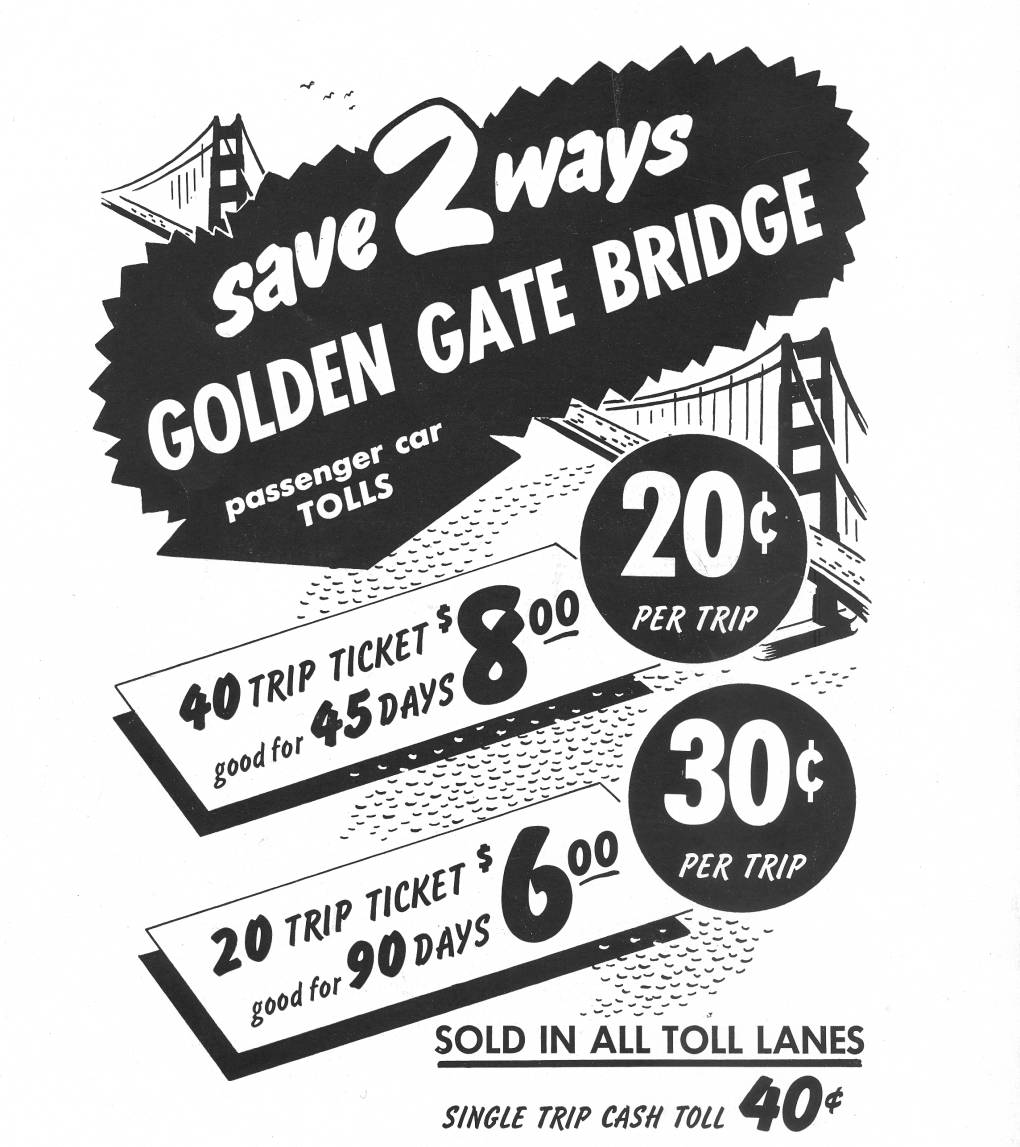

“The picture changes if you look at more of the toll history. Bridge directors actually reduced tolls three times — to 40 cents each way in July 1950; to 30 cents in February 1955; and to 25 cents in October 1955. A 40-trip book of commute tickets was priced at $7 after that final reduction.

“Those 1955 cuts were made in response to pressure from local politicians — notably state Sen. Jack McCarthy, a Republican representing parts of Marin and San Francisco — who argued that the district’s revenue from bridge tolls was far more than it needed to make ends meet.

“After the district voted in August 1955 to reduce the toll to a quarter, board member William Hadeler foresaw a future that could be toll-free if only cash weren’t needed to keep the bridge in good repair.

“‘We are not going to be content with a 25-cent toll,’ Hadeler said, according to what was then called the Daily Independent Journal (today’s Marin IJ). ‘As soon as conditions permit, I — and I am sure all of the directors — would like to see the toll reduced to 20 cents, to 15 cents, to 10 cents; and someday, if possible, no toll at all. But free tolls are something for the distant future. The Golden Gate Bridge is here for all time. It has to be operated and maintained so that it will always be here. And someone must pay the cost of those expenditures. That is why we have tolls.'”