In the Bay Area, about 12,500 – or 12 percent — of primarily working-age black men (ages 25 to 54) are, in a sense, “missing” from daily life. In other words, these men, who under different circumstances would be a part of their local communities, are not present. The black gender imbalance is greatest in Alameda and Contra Costa counties.

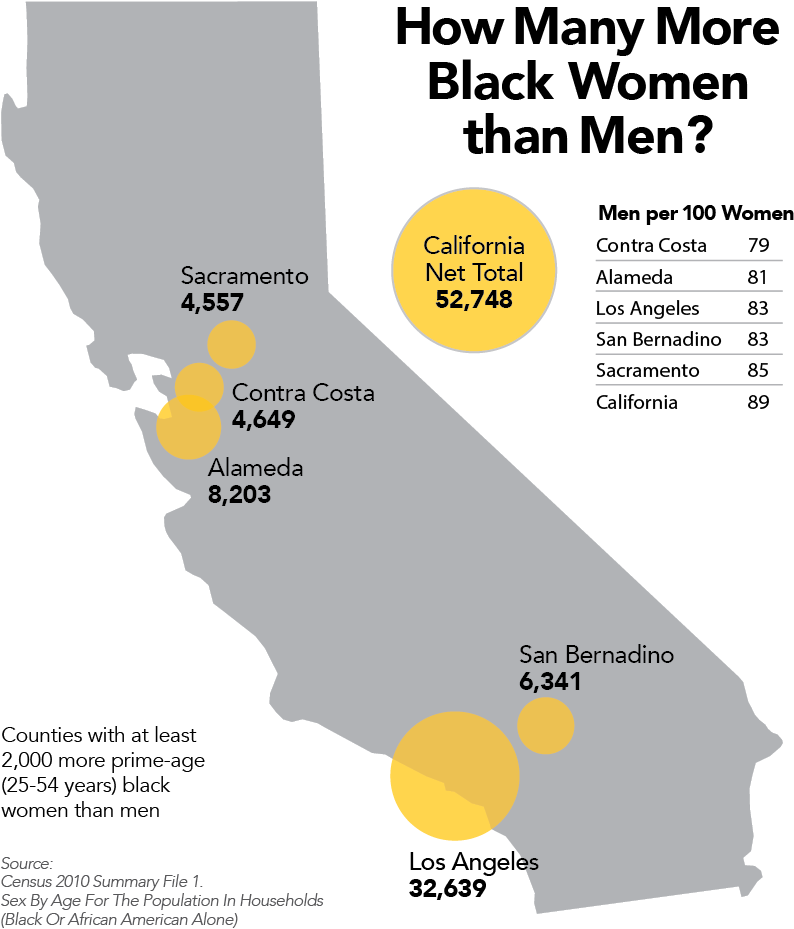

The gender imbalance among blacks throughout California resembles that in the Bay Area, for what appear to be similar reasons. Statewide, there are 89 black men for every 100 black women, according to our analysis. That amounts to roughly 53,000 more black women than black men living in California households. The imbalance is greatest in Los Angeles County.

While African-Americans make up about 6 percent of California’s total population, they make up nearly 30 percent of the state’s prison population.

The maps below show Bay Area and regional Los Angeles communities with the greatest gender imbalances among black residents. The imbalance of men to women is shown in absolute numbers and divided by designated U.S. Census tracts (a statistical subdivision of a county used for population counts). Only tracts with more than 200 black adults and a deficit of more than 50 black men are shown.

Our analysis assumes a roughly even male-to-female birthrate for every race and shows the number of “prime-age” adults between 25 and 54 years old living in households, as reported in the 2010 Census.

Tracts shaded in red have the largest gender disparities. Note that the geographically large Bay Area census tract 356002 includes parts of Richmond, Martinez and Hercules.

“The economic impact of this is huge,” said Brian Goldstein, Director of Policy and Development at the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice (CJCJ), a San Francisco-based criminal justice advocacy group. Not only are large numbers of black men removed from the workforce, Goldstein said, those released from jail or prison often find their earning potential significantly diminished.

Goldstein also points out that there are many hidden costs associated with such a big gender imbalance, including family instability and the loss of civic engagement.

“The collateral consequences," he added, "extend far beyond the individuals who are incarcerated.”

Additional factors

Higher mortality rates resulting from accidents, heart disease and, most notably, homicide also appear to affect the gender imbalance in black communities both in the Bay Area and statewide. Although the number of black homicide victims in California has fallen sharply over the last decade – from 758 in 2005 to 510 in 2014 – the rate remains disproportionately high: more than 30 percent of all homicide victims in the state are black. And almost 90 percent of these victims are men.

Demographers also point to a historical under-counting of black men in the national census, as well as high rates of black male military deployment and those living in other “non-institutional facilities” such as mental hospitals or homeless shelters.

These factors, however, pale in comparison to the impact of mass incarceration on the overall gender imbalance in the black community, both locally and statewide.