But the 2016 Election has been anything but typical.

To start, President-elect Donald Trump didn't win the popular vote; nearly 3 million more people voted for his opponent Hillary Clinton. Trump was also an unusually controversial and divisive candidate, whose fiery, racially-infused campaign rhetoric emboldened white nationalists and other hate groups. Critics label him a dangerous trickster with no government experience and deep financial conflicts of interest who poses a serious threat to America's democratic institutions.

Add to this, the flurry of recent headlines pointing to further evidence that Russia did indeed interfere in the election, in part to help Donald Trump win the White House, a longstanding allegation now supported by both the CIA and FBI.

As such, opponents are waging a last-ditch effort to block Trump's election, imploring electors to vote their conscience and choose someone -- anyone -- other than him. For weeks, electors have been besieged by emails, phone calls and even a celebrity video plea. But for that to happen, at least 37 electors in states that Trump won would have to abandon their party's nominee, denying him the requisite 270 electoral votes he needs to win the White House.

One Republican elector in Texas has already publicly announced his decision to not support Trump. And electors in three states have gone to court for the authority to vote as they please.

Nevertheless, the prospect of that many electors turning their backs on Trump is highly unlikely. But constitutionally, it remains possible. And that's giving Trump's opponents enough hope to keep fighting.

Some background ...

"The electoral college is a disaster for a democracy."

That was a tweet from Donald Trump on the eve of the 2012 election after it was predicted that President Obama would win the electoral vote despite possibly losing the popular vote to Mitt Romney (which he didn't).

He also tweeted: "We can't let this happen. We should march on Washington and stop this travesty. Our nation is totally divided!"

But what a difference four years can make. Trump has since had a dramatic change of heart.

After all, he has the Electoral College to thank for his unexpected victory, one of the biggest political upsets in U.S. history.

Trump won the race despite losing the popular vote to Hillary Clinton by what will likely be more than 2 million votes, after all the returns are counted, according to a New York Times estimate. As of Tuesday, Clinton was ahead by almost 1.75 million votes, with at least 2 million ballots still to be counted in Democrat-heavy California. That makes Trump the unlikely beneficiary of a confounding election process that, as a candidate, he consistently claimed was "rigged" against him.

Electoral math

So how, in the most famous democracy in the world, where everyone's vote is considered equal and the majority supposedly rules, is the loser of the national popular vote able to win the presidency?

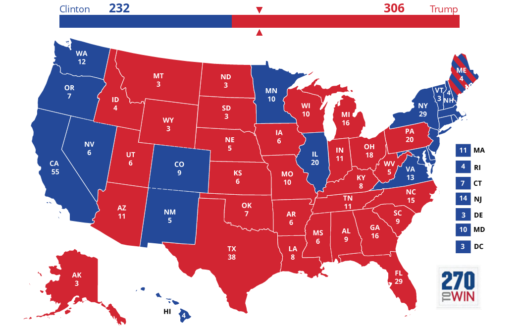

Bottom line, Trump might not have gotten the most votes, but he won them in the places that counted most -- albeit, by razor-thin margins. At the end of the day, Trump prevailed in most of the large, crucial battleground states, including Florida, Pennsylvania and Ohio, all of which went for Obama in the last two presidential elections. It’s no coincidence that the candidates spent an inordinate amount of time on the campaign trail in this handful of “swing states,” which ultimately decided the election. So, at the end of the day, regardless of how many more popular votes Clinton received, she won only 232 electoral votes to Trump’s 306 (assuming Michigan, which still hasn’t finalized its vote count, goes his way).

This is only the fifth time that the winner of the presidential election has lost the popular vote, but it’s also the second in less than 20 years: The last time, of course, was the hotly contested 2000 election, which Al Gore narrowly lost to George W. Bush despite winning more popular votes. And as happened then, the outcome of the 2016 contest has again renewed a chorus of demands to reform or flat-out eliminate a system that critics consider outdated and squarely undemocratic.

Some democracy, but not too much

The electoral process is all based on a set of rules drawn up more than 200 years ago by the founding fathers, a group of brilliant, wealthy white men who sought to create a system of government that reflected the will of the people ... but only up to a point. Give the voters (who at that point were limited to other wealthy white men) decision-making power, but keep that power in check in case they don't choose wisely.

In other words, the framers were pretty apprehensive about the idea of a direct democracy; the people should have power but not too much power. In the Constitution, they laid out a system of representative democracy, in which the people don’t make the big decisions themselves, but rather vote for qualified representatives to decide for them. As it is with Congress and the Senate, it's also the rationale behind the Electoral College, the system we still use to elect the president.

As the breakout Broadway star and Founding Father Alexander Hamilton wrote in "The Federalist Papers: No. 68," the purpose of the Electoral College is to preserve “the sense of the people,” while also ensuring that a president is chosen “by men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station, and acting under circumstances favorable to deliberation, and to a judicious combination of all the reasons and inducements which were proper to govern their choice. A small number of persons, selected by their fellow-citizens from the general mass, will be most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to such complicated investigations.”

He continues: “The process of election affords a moral certainty, that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications. Talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity, may alone suffice to elevate a man to the first honors in a single State; but it will require other talents, and a different kind of merit, to establish him in the esteem and confidence of the whole Union, or of so considerable a portion of it as would be necessary to make him a successful candidate for the distinguished office of President of the United States.”

Vestige of slavery

Some constitutional scholars note that slavery was also a major impetus for the creation of the Electoral College and the method of legislative apportionment. When the Constitution was drafted in 1787, a large majority of the nation’s fledgling citizenry lived in northern cities like Philadelphia and Boston, dwarfing the white population of the agrarian South. To give the South more influence, James Madison and other influential slave-holding members of the Constitutional Convention advocated for counting slaves, who made up an estimated 40 percent of the South’s population.

As Michael Klarman, a Harvard Law School professor, explains in "The Framer’s Coup," the framers “rejected direct election of the president mostly because they distrusted the people and because Southern slaves would not count in a direct vote.”

In the famously reached compromise, the framers determined that each slave would be counted as three-fifths of a person, a major power grab for Southern states, which were guaranteed much stronger national influence.

Klarman concludes: “The malapportionment in the Electoral College, which never had a very good justification, continues to exert influence today.”

A brief electoral refresher

OK, so if you happened to snooze through high school government class, here’s a quick and dirty Electoral College refresher (for a more detailed explainer on the process, check out this earlier piece):

When Americans go to the polls to “elect” a president, they’re not actually voting for the president, but rather a particular slate of electors, a somewhat random assortment of state party insiders, donors, and in some cases, fringe activists who have pledged to support the candidate from their party who wins the most votes in that state. The magic number is 270: Get that many electoral votes and you’re in the White House.

The number of electors in each state is based on the size of its congressional delegation (U.S. senators and representatives), which in turn is based on the state’s population. However, this has become a point of contention. Because every state, no matter how small, is guaranteed at least three electors (based on a minimum of two senators and one representative), a vote in sparsely populated states like Wyoming or North Dakota is technically worth more than a vote in crowded states like California or New York. (This cartoon by Andy Warner nicely illustrates the concept).

The electors then meet in their respective states 41 days after the general election (this year, it will be on Dec. 19), where they cast a ballot for the president and a second for vice president. As expressed by Hamilton, the founders envisioned the Electoral College consisting of statewide groups of deliberative bodies who would carefully consider the wisdom of the people’s choice, but be willing and empowered to change course if they deemed that choice foolhardy.

In modern-day elections, however, this process has largely become a formality. Unlike Hamilton's vision, the electors who represent us today are all but anonymous; even the most informed voters would likely be hard-pressed to know who their state electors are. (If you are curious about this, check out Politico's interesting guide to "The People Who Pick the President".) In fact, it can be argued that much of today's system bears little resemblance to the way the founders envisioned it.

In every state except for Maine and Nebraska, the candidate who wins the most votes (that is, a plurality) is supposed to receive all of that state’s electoral votes, regardless of how narrow the victory. It’s a winner-take-all system, which means that candidates may win some states by wide margins (as did Donald Trump in most Southern states like Tennessee and Alabama) and others by very slim ones (as he did in Florida, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin). And that’s what made it possible for Trump to win the Electoral College but lose the popular vote.

Defenders of the Electoral College argue that it forces candidates to pay attention to a wider swath of the country rather than focusing exclusively on densely populated urban centers. Advocates also say that the electoral system keeps presidential elections efficient, preventing the massive task of having to conduct a national recount in a close race.

Calls for reform

But in the wake of this election, a growing chorus of discontented citizens are pushing against the status quo.

One online petition has already gathered more than 4.5 million signatures since the election. It urges electors from some of the states Trump won to cast their electoral votes for Hillary Clinton.

“Mr. Trump is unfit to serve,” the petition states. “Secretary Clinton WON THE POPULAR VOTE and should be President.”

Although electors in some states are required to take a pledge to support their party’s presidential and vice presidential nominees – and some states can even replace or fine so-called faithless electors up to $1,000 for not voting for in line, there is no actual “Constitutional provision or Federal law that requires Electors to vote according to the results of the popular vote in their states,” according to the National Archives and Records Administration.

There have been a total of 157 faithless electors in U.S. history, according to the group FairVote (which notes that 71 of those votes were changed because the original candidate died before the votes were cast). None has ever been prosecuted for failing to vote as pledged. And more than 20 states have no state law or required pledge.

So technically, this could happen. But don’t hold your breath. At least 38 Republican electors would need to switch party allegiances to give Clinton the necessary 270 votes. You probably have a better chance of winning the Powerball lottery than seeing that happen. And even if there were enough Republican defectors to deny Trump the necessary 270 votes, they almost certainly would vote for another Republican candidate over Clinton. On the incredibly slight off-chance that neither candidate won 270 votes, the election would be decided by the Republican-controlled Congress.

Among the growing cadre of Electoral College critics (who are mostly Democrats), many are calling for changes to future elections. They include outgoing Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-California) who last week introduced "Hail Mary" legislation to eliminate the Electoral College altogether in favor of the popular vote.

"This is the only office in the land where you can get more votes and still lose the presidency," she said in a press release. "The Electoral College is an outdated, undemocratic system that does not reflect our modern society, and it needs to change immediately. Every American should be guaranteed that their vote counts."

The legislation calls for amending the Constitution, which would require a two-thirds majority vote in both the House and Senate, and ratification by three-fourths of the states.

Not likely to happen anytime soon.

Such discontent with the system is nothing new. There have been more than 700 proposed constitutional amendments to either “reform or eliminate” the Electoral College in the last 200 years. Obviously, none have been successful. But some have come close: In 1969, an amendment to abolish was endorsed by President Richard Nixon, and passed overwhelmingly in the House (338 to 70), but was ultimately filibustered and killed in the Senate.

State's take action