The term“opioids” refers to the very broad class of highly addictive drugs -- both legal and illegal -- that impact the body’s opioid receptors by blocking pain and sparking pleasurable sensations.

Morphine, methadone, hydrocodone (Vicodin), and oxycodone (OxyContin) are all popularly prescribed opioids, often used to treat chronic pain. Heroin, which is derived from morphine, has long been one of the most dangerous and commonly used illegal opioids. Fentanyl, a synthetic (man-made) opioid that’s 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, can be medically prescribed to treat severe pain, but it is now being illegally produced and sold on the street at an alarming rate.

There is a wide spectrum of opioid users -- many who take prescription drugs responsibly, with the consent of a doctor, to manage pain. However, an estimated 12 million people currently abuse prescription opioids, which means they take them without a prescription or in larger amounts and for longer than prescribed.

How did this become an epidemic?

The U.S. health care industry underwent a gradual shift in the 1980s and 1990s -- due in part to a number of influential articles in medical journals -- in the way health care providers approached pain management. Opioids had long been recognized as highly addictive, and were largely used primarily to treat intense pain from cancer and other severe illnesses. But based on a growing consensus that chronic pain was not being treated effectively, health care providers were increasingly expected to more routinely assess their patients’ pain levels.

This change in approach happened alongside more aggressive marketing tactics by big drug companies in an effort to sell opioid medications for non-cancer-related pain. This fueled a dramatic increase in the number of opioid prescriptions that doctors were giving to their patients. A class of drugs that was almost exclusively reserved for cancer patients was now being prescribed to a much wider group of patients experiencing various forms of chronic pain. In 2010, at the peak of this trend, there were more opioid prescriptions than residents in some counties, particularly in rural areas in the Rust Belt, the South and the Pacific Northwest.

As prescription pills flooded into communities throughout the country, many people got hooked through a steady supply from friends, family members and drug dealers.

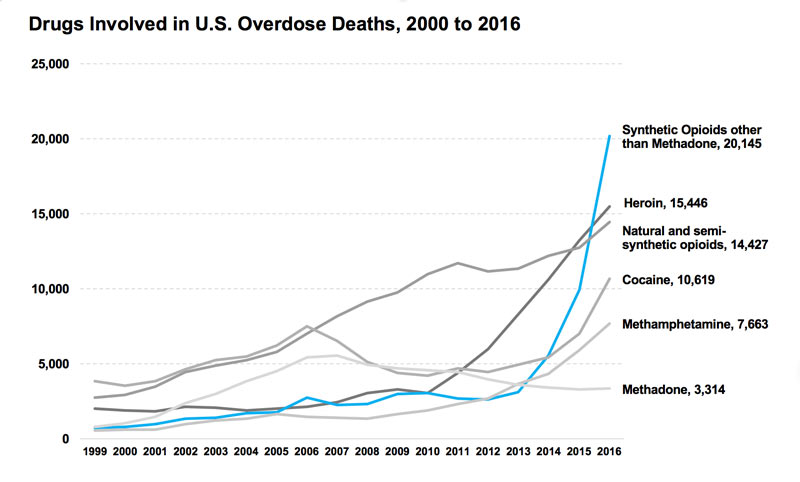

Since then, opioid prescription rates have declined, due in part to changes in policy and medical standards. But the overdose death rate has not followed suit. The once abundant supply of prescription opioids has been largely replaced by an influx of rampant abuse of heroin and illegally produced fentanyl, drugs that cost less, produce more intense highs and are much easier to get on the street.

Who is most affected by the crisis?

Opioid addiction is no longer limited to rural areas -- new research shows many suburbs and cities are now facing similar opioid abuse rates.

Prescription opioid overdose rates tend to be higher in older adults, while heroin overdose rates are higher in younger populations. And although more men currently die from drug overdoses, women are now dying from prescription opioids and heroin abuse at a rapidly increasing rate.

However, in contrast to the crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s, which hit poor, black, urban communities the hardest, the opioid crisis disproportionately affects white Americans. And many point to this racial divide as a key impetus for the dramatic shift in the way that lawmakers today are addressing the issue.

In the 1980s and 1990s, leaders from both parties waged a “war on drugs” -- passing laws that criminalized illicit substances and imposed increasingly strict prison sentences on drug users and dealers. Compare that with the softer approach more commonly taken now , one that focuses on rehabilitation rather than criminalization, as evidenced by President Trump’s recent declaration of the opioid crisis as a “public health emergency.”

The two maps below compare estimated age-adjusted drug overdose death rates per county in 1999 and 2016, as provided by the CDC. In 1999, the nationwide drug overdose death rate was 6.1 per 100,000 population (just under 17,000 actual deaths). In 2016, it had risen to 19.8 per 100,000 (63,632 deaths), an almost 275 percent increase. Although the crisis reaches across the nation, areas of Appalachia and the Southwest and Northwest have been particularly hard hit.

In the second map, click on individual counties for localized data, including the estimated number of actual deaths. The data includes all drug-related overdose deaths (of which opioids were the cause of about two-thirds). To see county-specific data for 1999 deaths on the second map, deselect "2016 Overdose Deaths" in the lefthand layers window. In the second map, you can also search and zoom in to specific locations by clicking the magnifying glass button on the bottom left and entering a place name or Zip Code

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

What’s being done to try to slow the epidemic?

Ending the epidemic is a massive undertaking that by most accounts is just getting started. Opioids, both legal and illegal, remain widely available, and the epidemic continues to claim about 100 lives per day. There is a shortage of affordable drug treatment programs in every state, and the federal government has been slow to allocate money to the crisis.

Ending an opioid addiction is often physically painful and can be incredibly difficult to manage. Until recently, many people believed that effective withdrawal treatment required extended stays in residential treatment facilities, a costly approach that many patients and public health institutions simply can't afford. It's also one that commonly focuses on abstinence, a strategy that's proved to not be consistently effective for long-term recovery

More recent evidence, however, has shown that opioid addiction can often be more successfully treated in non-residential primary care situations, especially with the use of closely monitored medication-assisted treatment options like methadone or buprenorphine -- both forms of opioids themselves -- a strategy that's significantly cheaper and far less disruptive to patients' lives.

Many health care workers view addiction as a medical condition, not a moral failing or criminal act, Yet possessing illegal opioids like heroin and fentanyl still comes with the risk of arrest and jail time. The epidemic won’t end, most experts agree, without also treating the underlying causes that lead people to opioids in the first place, including prevalent mental health issues.

Federal, state and local governments have taken some steps to treat current addicts as well as stanch the flow of opioids into communities.

Public health emergency: Last October, President Trump declared the opioid epidemic a “public health emergency,” which gives states more flexibility to use federal funds to fight opioid addiction and boost prevention efforts. However, the latest federal budget calls for only a 1 percent increase in federal funding for all drug prevention efforts, and Trump has yet to appoint a “drug czar” to lead the fight against the epidemic.

New limits on opioid prescriptions: Opioid prescriptions have been declining since 2010. Some states, like New Jersey, have limited the number of opioids that doctors can prescribe. Other states, backed by the Justice Department, have threatened to jail doctors who overprescribe the drugs. The CDC recently released guidelines asking doctors not to prescribe opioids for chronic pain. Despite these efforts, prescription opioids are still widely available. In 2016, there were still enough opioid pills prescribed to fill a bottle for every adult in the U.S.

Cutting off the supply of illegal opioids: In January, Trump signed the INTERDICT Act, which further empowers border patrol and customs officers to detect and stop illegal shipments of fentanyl.

Increased access to anti-overdosing drugs: Walgreens announced last October that it would stock Narcan, a nasal spray that can reverse a drug overdose. The spray will be available without an individual prescription in 45 states. CVS offers the spray in 43 states, also prescription-free. Narcan costs about $125 per dose. Its active ingredient is naloxone, which is also available in auto-inject form. But as demand for naloxone has increased, so has its price. The auto-inject format called Evzio now costs thousands of dollars, although price breaks have been negotiated by first responders and insurance companies.

The United States is dealing with the deadliest drug epidemic it has ever experienced.

The United States is dealing with the deadliest drug epidemic it has ever experienced.