Clicking on the “More search tools” link (highlighted in the screenshot above) exposes a variety of filters, including “Translated foreign pages.” This particular filter translates your search, and runs it in a wide variety of languages. It returns results in the language or languages with the most results:

![[presidential elections] translated foreign pages Translated foreign pages filter for [presidential election]](http://ww2.kqed.org/mindshift/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2012/05/presidential-elections-tfp-620x594.jpg)

You can stick with the automatically-selected languages, or select one or more of the 56 handled by this filter. The results do not appear in the language of origin, however, but are displayed in English, with the additional “Translated from” line in grey below the web address of each result to indicate the pages are actually written in another language.

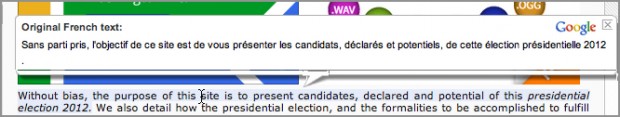

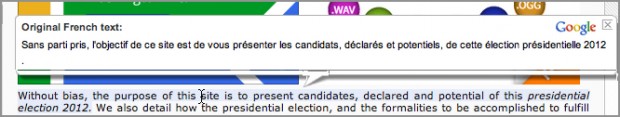

When you click on a specific result, you're taken to the page as it looks in the original, but with automatically generated machine translated English in place of the original text. By mousing over any phrase, you can view the original text.

This tool provides a powerful tour of the world with only a click. Within the search results for [presidential election], by simply changing the language to French or Arabic or Serbian, you not only transform the voices you encounter, but you also define--to some extent--the subject from the elections in France, to those in Egypt, to those in Serbia. Likewise, a search like [hollande presidential election] among German sources offers up a different slice of international perspectives.

These results are machine-translated by the same technology that runs Google Translate, which now translates as much text on a given day as you would find in a million books. Translations can take a bit of patience to read, and students will want to be careful about how literally they interpret the language they see. With guidance, however, students can find information that would simply not be accessible otherwise.

Take, for example, the student who was representing Portuguese-speaking Cape Verde at a Model United Nations conference back in 2010. He was assigned to the World Health Organization, where he was to play the part of Cape Verde in debates regarding world policy on dealing with infectious diseases. This student had read about a recent epidemic of Dengue Fever in Cape Verde, and had access to a variety of English-language documents outlining how other nations had pitched in to help with the medical crisis, and analyses of how Cape Verde handled matters. But the student wanted the Cape Verdean perspective, and wanted to know what the government had communicated domestically, and with those translations, he found them.

This particular tool can be used in reverse to provide scaffolding for English Language Learners, too. Recently, a group of high school students who happened to be refugees from Mongolia came to a search class. They used Google Mongolia’s translated foreign pages filter to access English-language pages about the American Revolutionary War, but view them in their native tongue, to help gain some basic vocabulary and concepts to support their English-language reading.

SITE: SEARCHING BY DOMAIN

Another option is simply to include the site: operator in a basic search, followed by a country’s domain. The site: operator works in most search engines.

For example, students who want to read about what sites out of Brazil have to say about explorer Pedro Alvares Cabral only need search for [pedro alvares cabral site:br]. This search retrieves specifically websites that end with .br, but not those originating from Brazil but ending with .com or other such top level domains. Note there is no space between the site: and the country abbreviation.

![[pedro alvares cabral site-br]](http://ww2.kqed.org/mindshift/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2012/05/pedro-alvares-cabral-site-br-620x688.jpg)

Notice that the above search uses only the explorer’s name, which works in both English and Portuguese, so you get results in both languages. Alternately, the search [captain pedro alvares cabral site:br], starting with the English word captain only brings back English-language sources:

![[captain pedro alvares cabral site-br]](http://ww2.kqed.org/mindshift/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2012/05/captain-pedro-alvares-cabral-site-br-620x720.jpg)

SEARCH BY REGION

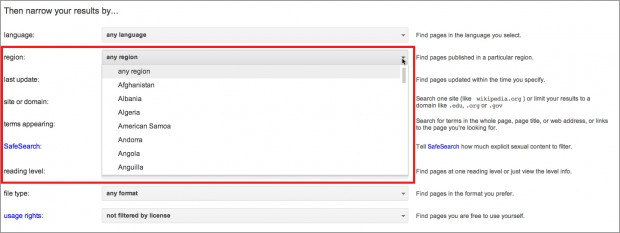

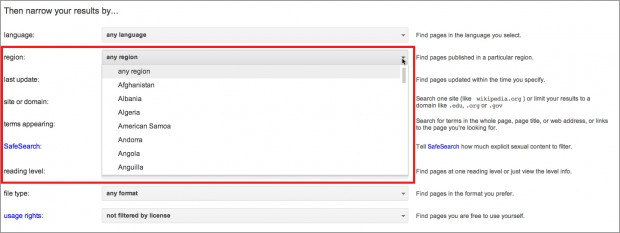

A broader way to capture sites originating in a specific country is to use the “region” search in Google’s Advanced Search.

Run a basic search, and then find the cog icon in the upper right-hand corner of the screen. Click on it to access the Advanced Search link.

![[russia japan relations]](http://ww2.kqed.org/mindshift/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2012/05/russia-japan-relations-620x297.jpg)

The second section of the Advanced Search page, labeled “Then narrow your results by...” offers a chance to pick a region from which you want all of your results to originate. Note that, if you search using English words, your search results will contain pages that have your terms in English--no translation takes place with this tool.

Results will differ, however, which you can see by comparing the results for the same search terms when filtered by pages from Japan:

![[russia japan relations] japan results](http://ww2.kqed.org/mindshift/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2012/05/russia-japan-relations-japan-results-620x628.jpg)

And from Russia:

![[russia japan relations] russia results](http://ww2.kqed.org/mindshift/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2012/05/russia-japan-relations-russia-results-620x702.jpg)

It's interesting to compare the results to each other--and even to the results found with Translated foreign pages. With Translated foreign pages, students get the perspective of Russian or Japanese speakers communicating with each other, while the English-languages sources represent a position targeted at the English-speaking world. Taken together, these results can help students begin to access a more sophisticated picture of the world around us.

The wired world has made it possible for people from all across the globe to connect and learn from each other. In a few days, New York Times reporter Nicholas Kristof will host a Hangout and interview United Nations Ambassador Susan Rice during school hours. In classes across the country, students are hearing about the Greek debt crisis; presidential elections in France, Serbia, Armenia, Greece, and Egypt, as well as Secretary Clinton’s recent travels to China.

The wired world has made it possible for people from all across the globe to connect and learn from each other. In a few days, New York Times reporter Nicholas Kristof will host a Hangout and interview United Nations Ambassador Susan Rice during school hours. In classes across the country, students are hearing about the Greek debt crisis; presidential elections in France, Serbia, Armenia, Greece, and Egypt, as well as Secretary Clinton’s recent travels to China.

![[presidential elections] Search results for [presidential elections]](http://ww2.kqed.org/mindshift/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2012/05/presidential-elections-620x572.jpg)

![[presidential elections] translated foreign pages Translated foreign pages filter for [presidential election]](http://ww2.kqed.org/mindshift/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2012/05/presidential-elections-tfp-620x594.jpg)

![[pedro alvares cabral site-br]](http://ww2.kqed.org/mindshift/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2012/05/pedro-alvares-cabral-site-br-620x688.jpg)

![[captain pedro alvares cabral site-br]](http://ww2.kqed.org/mindshift/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2012/05/captain-pedro-alvares-cabral-site-br-620x720.jpg)

![[russia japan relations]](http://ww2.kqed.org/mindshift/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2012/05/russia-japan-relations-620x297.jpg)

![[russia japan relations] japan results](http://ww2.kqed.org/mindshift/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2012/05/russia-japan-relations-japan-results-620x628.jpg)

![[russia japan relations] russia results](http://ww2.kqed.org/mindshift/wp-content/uploads/sites/23/2012/05/russia-japan-relations-russia-results-620x702.jpg)