The SLI has had low visibility so far. Started in 2011, encouraged by the Council of Chief State School Officers (the state superintendents of public instruction group that was one of the driving forces behind the Common Core State Standards), and funded by the Carnegie Corporation and Gates Foundation, the SLC has signed on nine states with the promise of creating a less expensive, more connected way to store student data with the potential to make student learning more personal.

WHERE WOULD THE DATA GO?

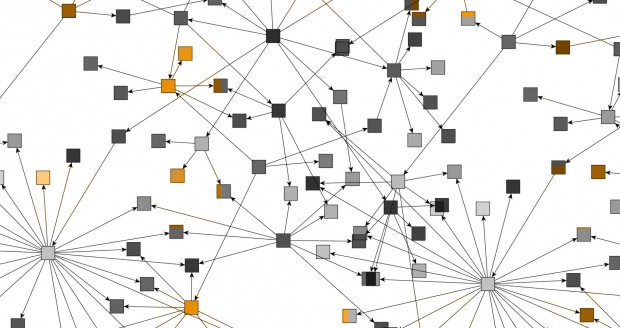

Perhaps the best way to understand the SLI initiative – this nuts-and-bolts, multi-state, grand-vision education technology project that just went into its pilot alpha release – is to visualize plumbing. Think of twin buckets in the cloud:

1. The main part of the Shared Learning Infrastructure is a huge, carefully structured bucket: the data store/warehouse, which holds, well, a bucket-load of student data across grades and subjects, such as individual student names, demographic information, discipline history, grades, test results, teachers, attendance, graduation requirements, even detail of standards mastered.

This is all data that schools already have, but it’s not necessarily stored all in the same place, in the same way (think of the historic tech disconnect of Beta vs. VHS videotape formats), or even synched and easily available when it’s needed. SLI is designed to serve all these needs and be based on technology that will be open source, free for states and districts to use, modify and share -- all appealing to administrators.

2. A second, companion bucket inside SLI is information about instructional content and materials. But it doesn’t hold the instructional resources themselves. This bucket provides pointers to the resources everywhere on the web, leveraging tagging and indexes of the Learning Resource Metadata Initiative and U.S. Department of Education Learning Registry. And these resources, through the pointers, are aligned to the new Common Core standards. That alignment provides a connection between the instructional materials and the student test data in the first, big bucket.

3. The third part isn’t another bucket. It’s spigots and faucets that stick out of the buckets – the APIs, or Application Programming Interfaces. APIs are simply a way for school administration, instructional and assessment software outside of the bucket to receive a flow of information from inside the bucket and pour its own back in. This is what the school, teachers and students primarily work with: the software that works with the SLI, connected by the APIs.

The hope is that schools and students will be able to benefit when these pieces are connected. If a student changes schools, either by moving from one grade to another or simply moving, that student’s data would follow her in a consistent format (assuming the new school is also in a state that uses the SLI). Then, it's theoretically easier to understand a student’s -- or even an entire student group’s -- performance over time throughout their educational career, because all of that granular data, regardless of grade, is in one bucket.

Teachers and students could also benefit through easier-to-personalize instruction – a holy grail of education technology. Since the bucket of student data is explicitly tied to the Common Core standards, and the second bucket of content in the SLI is also tied to the same Common Core, connecting the two could create a clearer path to what needs to be learned based on what a student has shown he or she (or a group of students with similar learning patterns) does, or doesn’t, understand. As Brandt Redd, senior technology officer for education programs at the Gates Foundation, noted in a presentation at an education industry conference, SLI is part of the cycle, “How did I do? What don’t I know? How do I learn this? … That data isn’t getting back to the teachers and students.”

For their part, the pilot districts in the initial states see practical appeal in having one place to store and pull data rather than try to extract it from multiple administration, instructional and testing programs, all of which may not play nicely together. Tom Stella, assistant superintendent of Everett Public Schools in Massachusetts, summed up his district’s perspective at a Software and Information Industry Association SLC workshop this spring in San Francisco: “The fewer places I have to go to get assessment data,” the better.

CARROTS AND STICKS FOR EDUCATION COMPANIES

But there are still a number of issues that remain before the spigots can be turned on. One of the biggest, of course, is that the technology all works, which is the point of a new developer’s Sandbox that lets companies test applications.

A second is the privacy and security of student data. On its website, the SLI prominently addresses this concern by stating that states, districts and schools "retain ownership and control of their data," any existing privacy and security policies will continue, and it'll be the districts -- not the SLC -- that will determine which apps get data access." The SLC adds that it's building the technology so schools using it can be in compliance with the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA).

A third is how many education companies will build products that connect to the SLI and take advantage of its features.

This last piece isn’t a small detail. It’s pretty clear that the SLI could easily replace a good part of the data back end of a number of products, including student information systems. (One SLC official estimated, very cautiously, that 10-20% of such products are related to storing data.) Having ready-built student data storage could also make it easier for some companies to compete with those who already offer their own proprietary “personalized” products that they’ve engineered independently, and cause those companies to lose a competitive leg up.

With the education industry, SLC is using both the carrot and the stick. The carrot is the official stance.

“Students aren’t going to have a great educational experience (simply) because you solved the data problem again,” said Gates’ Sharren Bates at the Software and Information Industry Association’s Ed Tech Industry Summit this spring.

Instead, she urged, let the SLC solve the data storage problem one more time, and let the industry focus on the tools that use it. Other advantages being touted to the industry are that early-stage and established companies will no longer have to figure out how to integrate their software with data software used by each district and state – as long as the software works with the SLI’s APIs, it will work.

The stick appears to be coming from the pilot states and districts themselves. At the same San Francisco workshop, at least one of three state and district representatives implied they wouldn’t even look at a product that didn’t work with the SLI once they start using it. But the promise for companies is based on the assumption that enough states and districts beyond the pilot phase will adopt it, creating a critical mass of potential customers to make education technology developers want to pay attention.

A myriad of other issues include how software that interacts with the SLI will be approved (both as a technical and policy matter) and who will approve it, the computing power and bandwidth required of schools, and – key – who will pay to maintain the Infrastructure and do new SLI development after it’s launched and foundation financial support ends.

The SLC has made it clear it’s aware of these issues and appears to be working in a similarly low-key-yet-persistent way to address them. In the meantime, its SLI has gone into alpha release as of late June and plans a final release in December 2012 (assuming the Mayans don’t intrude). Committed to take part in the pilot are at least one school district in each of Massachusetts, New York, Illinois, North Carolina and Colorado, to be followed by Louisiana, Georgia, Delaware and Kentucky.

It’ll likely be some time in 2013 before we find out if the SLI will fully complete that complicated waterworks – or if it will become a fancy set of publicly owned buckets, attractive and exciting in design, but with spigots that remain closed because no one has constructed pipes to accept and renew the flow of data.