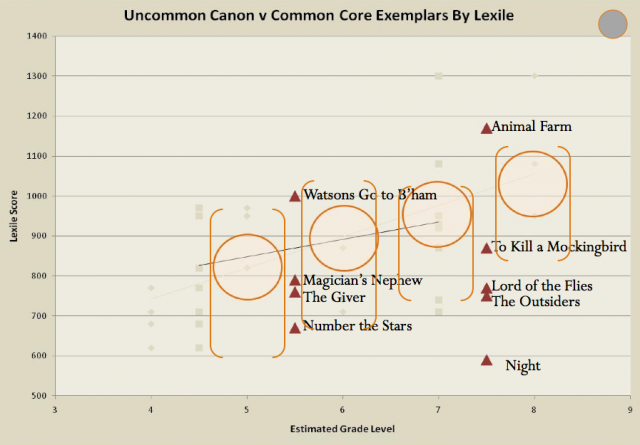

In a recent New Republic essay on the new Common Core reading standards, University of Iowa English professor Blaine Greteman complained that the Common Core’s method of deciding text complexity -- the Lexile score -- is making a mockery of learning to read by assigning books a “complexity score” between 0-1600, based mostly on vocabulary words and sentence length.

Under this new standard of judging a book, said Greteman, Huckleberry Finn becomes too easy for high schoolers, and Raymond Carver’s Cathedral scores in about the same range as Curious George Gets a Medal. “Few would oppose giving teachers better tools to challenge students, but this approach seems badly flawed,” Greteman wrote. “Lexile scoring is the intellectual equivalent of a thermometer: perfect for cooking turkeys, but not for encouraging moral growth.”

According to the Common Core English Language Arts Standards website, however, the Lexile isn’t the only measure of reading difficulty; the standard for measuring text complexity is measured in three ways: the quantitative evaluation (the Lexile score), the quantitative (levels of meaning, structure, and clarity), and “matching reader to text and task” (motivation, knowledge and experiences). In this way, defining text complexity for students is actually a little more complex than just assigning it a score: for example, Toni Morrison’s Beloved (score: 870L) may fall in the fifth-grade-range for its word choice and syntax, but the subject matter makes it a poor choice for 11-year-olds.

But many teachers have yet to begin assigning harder, Common Core-approved books, and the reasons why are unclear. According to a recent Thomas B. Fordham Institute report, a survey of teachers shows that, while many are aware of Common Core’s requirement for assigning harder books, few have yet to implement the changes because they are more focused on reading skills. “An astonishing 73 percent of elementary school teachers and 56 percent of middle school teachers place greater emphasis on reading skills than the text,” researchers wrote, “high school teachers are more divided, with roughly equal portions prioritizing either skills or texts.”