For subjects like math and foreign language, which are traditionally taught in a linear and highly structured context, using more open-ended inquiry-based models can be challenging. Teachers of these subjects may find it hard to break out of linear teaching style because the assumption is that students can’t move to more complicated skills before mastering basic ones. But inquiry learning is based on the premise that, with a little bit of structure and guidance, teachers can support students to ask questions that lead them to learn those same important skills -- in ways that are meaningful to them.

This model, however, can be especially hard to follow in public school classrooms tied to pre-set curricula. Class time, class size, assessments, resources, student buy-in, administrative pressures, and students' learned helplessness are just a few of the reasons why it can be challenging to create learning experiences that are deep, authentic, and driven by inquiry, according to participants at EduCon 2.6 hosted by Science Leadership Academy (SLA), a public high school in Philadelphia recently.

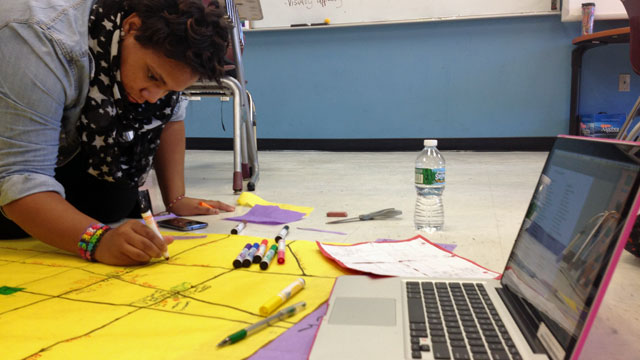

Science Leadership Academy, which has an established track record as an inquiry-based school, has just opened a second campus in Philadelphia called the Beeber school, whose teachers are still adapting to the inquiry model. With one freshmen class and a new crop of teachers still adjusting to project-based and inquiry driven approaches to learning, the school is a good model for learning how these complex ideas flesh out.

“You have to spend a lot of time and a lot of energy supporting kids to unlearn how they’ve been taught to learn for the majority of their lives,” said Marina Isakowitz, a ninth-grade math teacher at Beeber. Students at both SLA campuses come from public middle schools across the city and enter with varying levels of proficiency and very little experience with inquiry learning.

Isakowitz starts the year by asking lots of low-stakes, but complex questions as a way of scaffolding a new kind of learning for her students. Gradually, she says, they realize that this math class isn't going to be like others they've been in and they begin to understand and appreciate the freedom they've been given. It’s about providing just enough structure that the class holds together, but not so much that teachers are telling students what to do and how to do it.